The Attacking Ocean (31 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Mobility versus sedentary living: Poverty Point’s demise may be a classic example of increased vulnerability to rising water on the part of more permanent settlements. The change was not instantaneous; people and individuals respond to climatic events in complex ways. As more elaborate ancient societies came into being in later times, it’s noticeable that many villages lay on slightly higher, better-drained ground above the floodplain, even if they were near it. Over many centuries, people living along the river and in the bayous and swamps of the delta adapted effortlessly to a regime of flood and sea surge, an equation that changed dramatically with the arrival of European settlers. The cumulative effects of human efforts to control the river and its capricious flooding have now brought rising sea levels to the forefront in the complex minuet of ocean, river flood, and silt accumulation.

THE DANCE FLOOR is the shallow delta that forms the mouth of the river. As the Mississippi approaches the Gulf Coast, the current slows and deposits fine alluvium. Over the past five thousand years, the southern coast of Louisiana has advanced between twenty-four and eighty kilometers, forming twelve thousand square kilometers of coastal wetlands and extensive tracts of salt marsh. The latest cycle of delta development began as sea levels rose at the end of the Ice Age some fifteen thousand years ago. At the time, the mouth of the river was farther out in the Gulf, the current shoreline beginning to take shape about five thousand to six thousand years ago, when sea levels stabilized somewhat. Since then, the river has changed course repeatedly, as shorter and steeper routes to the Gulf have emerged upstream. As the river shifted, so the old delta lobe into the Gulf would lose its supply of alluvium, then compact and subside, retreating as the advancing ocean formed bayous, sounds, and lakes.

The Mississippi delta has always been a landscape of shifting currents, tides, and mudflats. This is a waterlogged, now-vanishing world, where you

canoe through forests and occasional open clearings, where there is almost no solid ground. A confusing mosaic of forested basins and streams form the fretwork of the delta, which absorbs the flood and holds the water until it escapes to the Gulf. When floods spread water out over the surrounding countryside, the water slows and deposits silt, the finest dropping at the edges, closer to the river, where natural levees form.

Such levees were where the first European settlers built forts. In 1718, the settlement that was to become New Orleans rose on a natural levee, only to be waterlogged by a high flood. There was nowhere to go, so the settlers raised artificial barriers. At first, the main levee was just under a meter high, raised in part by a law requiring homeowners to do so—not that many of them did. Fortunately for the growing settlement, the floods could spread widely on the eastern bank of the river where there were no artificial levees. In 1727, the French colonial governor proudly announced that the levee was complete. Nevertheless, the city was inundated in 1735 and again in 1785. The intervals between severe floods were long enough that generational memory faded, but the levees were slowly extended along the west bank as far as the Old River, some 322 kilometers upstream and along the east bank as far as Baton Rouge. The levees were far from continuous, mainly protecting plantations. Elsewhere, the flood poured over the countryside as it had always done. Many plantation houses rose on the only higher ground—ancient Indian burial mounds.

4

The more levees confined the river, the more destructive floods became when they broke through human barriers. By the mid-nineteenth century, it was clear that even raised levees would not contain the river as flows increased. Congress passed the Swamp and Overflow Lands Act in 1850, which deeded millions of hectares of swampland to the states. They in turn sold the swamp to landowners to pay for levees. The new owners drained most of the swamps, converted them into farmland, and then demanded larger and better levees to protect their investments. Catastrophic floods and levee breaks in 1862, 1866, and 1867 finally prompted Congress to form the Mississippi River Commission, charged through the Army Corps of Engineers to “prevent destructive floods.”

The most ruinous inundation of the nineteenth century came in 1882, at which point it was becoming apparent that the Atchafalaya River could become the new main course of the Mississippi. By now the river flowed high above the surrounding landscape, confined only by its levees, a disaster waiting to occur, which finally transpired with the flood of 1927. This caused multiple breaches and destroyed every bridge across the river for hundreds of kilometers. Sixty-seven thousand square kilometers of surrounding country vanished underwater.

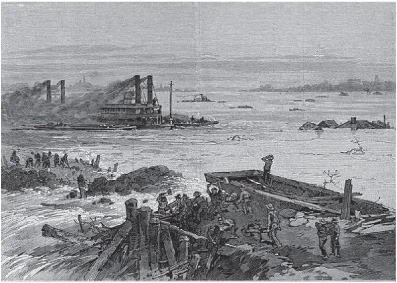

Figure 13.3

Repairing a levee on the Lower Mississippi. Drawing by Charles Graham. Author collection.

The Flood Control Act of 1928 provided funds for coordinated river defenses that were still incomplete in the 1980s. This time, the corps did more than raise levees. They straightened parts of the river, built spillways, like that at Bonnet Carré, nineteen kilometers west of New Orleans, which diverted water away from the city and into Lake Pontchartrain during a major flood in 1937. In places, levees now rose to more than nine meters, but increasingly the Army Corps turned its attention to the Atchafalaya, which flowed into one of the largest river swamps in North America.

Without human interference, the Lower Mississippi’s floodwaters would disperse widely over the delta plain through many outlets. Virtually

the entire delta would be covered not only with floodwater but also with fine sediment derived from mountains hundreds of kilometers away. As the writer John McPhee remarks, “Southern Louisiana is a very large lump of mountain butter, eight miles thick where it rests upon the continental shelf, half of that under New Orleans, a mile and a third at Red River.”

5

Deposits like this compact, condense, and sink. McPhee calls the delta “a superhimalaya upside down.” The subsidence continues despite human intervention. Until about 1900, the Mississippi and its tributaries compensated for the subsidence with fresh sediment that came down each year. The delta accumulated unevenly but on the positive side of the geological cash register, as channels shifted and decaying vegetation sank into the flooded silts. The vegetation itself grew as a result of nutrients supplied by the Mississippi.

Before the days of flood defenses, the river spread across the surrounding country quite freely and in many places, except at low water, when it stayed within its natural banks. Today, over three thousand kilometers of levees constrain the river until Baptiste Collette Bayou, ninety-seven kilometers downstream of New Orleans. The delta has lost silt for a century and southern Louisiana is sinking. Meanwhile the river with its levees shoots fine river sediment out into the Gulf of Mexico—some 356,000 tons of it a day. The water rises ever higher behind the levees as the surrounding landscape continues to subside. McPhee calls the delta “an exaggerated Venice, two hundred miles wide—its rivers, its bayous, its artificial canals a trelliswork of water among subsiding lands.”

6

The entire delta is a highly vulnerable, threatened landscape. About half of New Orleans is as much as 4.6 meters below sea level, hedged in between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi. The richest inhabitants live on the highest ground by the river. The poorest dwell at lower elevations in the most vulnerable locations of all. The city receives abundant rainfall, often torrential downpours that cause serious flooding within the river defenses, as happened with Tropical Storm Isaac in 2012. There are no natural outlets, so the water has to be pumped out, which tends to lower the water table and increase subsidence. The pumps, invented by engineer A. Baldwin Wood during the early twentieth century, allowed

the city to expand to ever-lower elevations; there was no space elsewhere.

7

New Orleans is so waterlogged that the dead are buried in cemeteries aboveground. Even from the slightly higher ground of the French Quarter, you look up at the levees and passing ships, their keels well above the city streets.

New Orleans has distinctive levee problems, not least that of the waves caused by the wakes of passing vessels. Everywhere, the high water line is rising as the speed of the confined water from upstream increases and the levees themselves subside. Down at the coast, the shortage of river silt has led to erosion, to the tune of some 130 square kilometers of marshland a year. Louisiana is 4 million square kilometers smaller than it was a century ago. Half a kilometer of marsh reduces the height of a storm surge from offshore by 2.5 centimeters. With the disappearance of 130 square kilometers of coastal barrier, the Mississippi equivalent of the Bangladeshi mangroves is drastically reduced. The vanishing marshes caused the corps to build an encircling levee around New Orleans, turning it into a fortified city—this before one figures in the sea level rises of the future.

At this point, many experts believe that the coast is beyond salvation, as entire parishes vanish and nutrient and sediment starvation wreak

havoc on the coastal landscape. Today, much Mississippi water flows down the Atchafalaya, which is the main route by which severe floodwaters reach the Gulf. Morgan City, Louisiana, has a flood stage about 1.2 meters above sea level and lies directly in the flood’s path. Huge walls 6.7 meters high surround the small town, which must be one of the most vulnerable human settlements on earth.

8

It is as if the city dwells atop an occasionally active volcano, its fate decided by flood control installations up at Old River, far upstream. This is apart from the storm surges caused by hurricanes. Weather conditions over 42 percent of the United States determine the long-term survival of Morgan City. Floods here last not weeks as they do upstream, but months, for the more people upstream protect themselves with rings of levees, the more water arrives downstream.

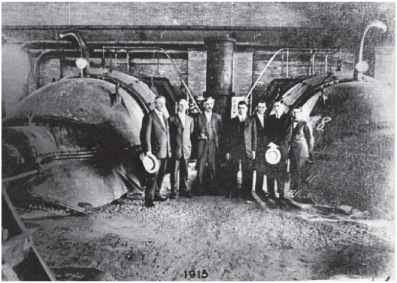

Figure 13.4

The dedication of A. Baldwin Wood’s pumping station in New Orleans, 1915. Author collection.

THANKS TO HUMAN activity, the Gulf Coast is sinking, sea levels are rising, and humans have effectively reversed nature. Or have they? This is hurricane country, and when such storms arrive they tear into the coast and accelerate erosion dramatically, making for an even more severe threat of destruction from the south than from the north.

Hurricanes entered recorded delta history dramatically in 1722, when one such storm led some French settlers of New Orleans to suggest that the city was uninhabitable. In 1779, another even more severe hurricane razed the city completely. A long history of devastation of barrier islands and inland villages also haunts the coast, but people have always stayed—to farm, to fish, and, in more recent times, because of oil. Rising sea levels compound the problem as they encroach on the eroding and subsiding delta shore. By the 1970s, the estimated annual loss was about a hundred square kilometers a year. The rate has slowed since then, as oil and gas activity has declined somewhat and measures were taken to reduce the loss, which now stands at somewhere between sixty-five and ninety square kilometers annually. Then there are sea surges, which created some seven hundred square kilometers of open water at the expense of wetland in the 2005 hurricane season alone.

In earlier times, before human interference, sediment maintained the

elevation of the wetlands and fed the offshore barrier islands, many of which are now disappearing in the face of hurricanes and rising sea levels. Tidal gauge data for Louisiana record a sea level rise of nearly a meter over the past century, most of it caused not by global changes in ocean volume but by subsidence. If the local sea level were to rise 1.8 meters between now and 2100, all efforts to restore the wetlands would be canceled out and New Orleans would be seriously threatened. This is why Hurricane Katrina was a defining moment in the adversarial relationship between humans and the ocean.