The Attacking Ocean (8 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Around 5800 B.C.E., the effects of the Laurentide meltdown receded as the Gulf Stream resumed its normal circulation. Warmer, westerly airflows resumed over the Mediterranean; high pressure settled over the Azores. Persistent westerly winds caused temperatures to rise over Europe, leading to a “climatic optimum” that lasted for two thousand years. Before 6000 B.C.E., farming societies had already moved from the Aegean region onto the Great Hungarian Plain and into the Danube River Basin. They prospered in the milder conditions, so much so that people in

northern Greece and what is now Bulgaria dwelled at the same locations for many centuries.

3

The same warm conditions caused sea levels throughout the Mediterranean to rise once more in response to the mass of water added to the ocean by the collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet. During the cold centuries, the Mediterranean was about fifteen meters below modern levels. By about 5600 B.C.E., rising seawater was lapping at the natural berm that separated the Sea of Marmara from the glacial Euxine Lake, which lay about 150 meters lower on the other side. The inevitable then transpired: The berm was breached, and the Euxine Lake became a brackish sea.

4

The flooding of the Euxine was an environmental change of truly epochal dimensions. But what were the consequences for the farmers living around the lake? We can imagine the sudden confusion as the lake began rising and the water became saltier by the day. The encroaching inundation would have drowned lakeside marshes and swamped growing crops. Canoe landings would have vanished within days; river deltas would have been flooded by muddy water. Thousands of dead fish would have floated in the newly brackish water. Soon afterward, long-established villages with their houses and storage bins would have vanished under the flood. The helpless villagers would have had some time to recover their possessions and empty their grain bins, and to move their herds to higher ground. However much time they had, many communities must have suffered badly from hunger until they were able to establish new villages and clear land away from the rising lake. Psychologically, the moves would have been traumatic, for the lands protected by their revered ancestors would have vanished forever.

The dynamics of life by the lake had changed completely. Villages once well back from the lake now lay at the heads of bays or on exposed shorelines. Many communities must have settled earlier along the innumerable small rivers and streams that led inland to an unknown world of endless forests. They would have moved inland with their herds, dispersing in many directions, following patches of lighter soil and more easily cleared land. Within a few generations, some of these farmers

had emerged on the Bulgarian plains and made their way up the Danube River basin into the heart of central Europe, where farmers had never ventured before. In one of the most significant population movements of human history, the descendants of farmers displaced by the rising Black Sea settled a band of easily cultivated glacial soils and river valleys from western Hungary to the North Sea.

IT TOOK ABOUT ten thousand years of warming and rising sea levels to bring the Ice Age Middle Sea close to its current levels. By about 5000 B.C.E., coastlines had basically stabilized near modern heights, although adjustments to higher sea levels continued to persist, especially as rivers’ flows became more sluggish and silt brought down by spring floods accumulated on coastal floodplains rather than being carried offshore into deep water. Nowhere in the Mediterranean world were these effects more marked than along the Nile, but, unlike the Euxine flood, the changes in what is now Egypt unfolded over thousands of years.

A century ago, long before the building of the Aswan Dam during the 1960s reduced silt levels, one sensed the presence of the Nile far offshore from the Egyptian coast. Deep layers of silt and river mud colored inshore waters and extended far offshore. That peripatetic Greek traveler Herodotus experienced the approach to the Nile firsthand twenty-five centuries ago: “The physical geography of Egypt is such that, as you approach the country by sea, if you let down a sounding line when you are still a day’s journey away from land, you will bring up mud in eleven fathoms [twenty meters] of water. This shows that there is silt this far out.”

5

The landfall on a low coastline in front of the prevailing north wind required nice judgment. Herodotus must have watched as his skipper used a lead and line tipped with wax that brought up river silt to calculate his distance offshore.

As they made landfall, Herodotus and his fellow passengers would have gazed on a low-lying, hazy shoreline marked by occasional palm trees and long, sandy beaches. The Nile delta was somewhat of an anticlimax for travelers who had braved the ocean in expectation of ancient

wonders. There were no temples or monuments wrought in stone along this featureless coast, apart of course from the marvels of their destination, a growing Alexandria, soon to become one of the great cities of the classical world. Many centuries later, Florence Nightingale of Crimean War nursing fame aptly wrote of the surrounding landscape in 1849: “The dark colour of the waters, the enormous unvarying character of the flat plain, a fringe of date trees here and there, nothing else.”

6

One travels by donkey or boat across a level obstacle course of irrigation canals, small fields, and villages. Tales of the Nile with its wondrous summer inundation had spread far and wide by Herodotus’s time, but the river lacked a spectacular estuary crowded with oceangoing ships. Instead, it dissipated into an enormous fanlike delta several days’ journey upstream from the Mediterranean Coast.

Herodotus thoroughly enjoyed his time in Egypt. His

Histories

masked the Nile valley in a delicious mélange of fact and fantasy. He correctly described ancient Egyptian mummification of the dead, fantasized that the Pyramids of Giza owed their building to pharaoh Khufu’s daughter’s earnings from prostitution, and recorded all kinds of gossip imparted by priests who lived off gullible tourists. But for all his tall stories, he realized that Egypt and its people depended on the Nile’s summer flood and the fertile soils of its great delta. Life in the Nile valley involved a delicate balancing act with an environment marked by unreliable floods and ever-changing sea levels. Herodotus remarked prophetically that should the Nile cease to bring water to the delta, then the Egyptians, with virtually no rainfall, would suffer torments of starvation like the Greeks.

At 6,650 kilometers, the Nile is the longest river in the world, flowing almost directly south to north. In its more northerly reaches it passes through some of the driest landscapes on earth.

7

In Herodotus’s day, no one had any idea of the length of the Nile or of the source of its waters. The flood arrived at the First Cataract upstream of Egypt’s frontier town Swenet, now Aswan, about 1,127 kilometers south of the Mediterranean, in early summer, seemingly by magic. As the inundation rumbled over the rocky granite outcrops, the ground trembled, so much so that the Egyptians believed that the river originated in a vast under

ground cavern below the cataract. They made offerings to the rain god Khnum on Abu (Elephantine) Island in the middle of the river, so named because of its associations with the desert ivory trade. Here a Nilometer, a graduated column, allowed priests and officials to estimate the height of the impending flood downstream.

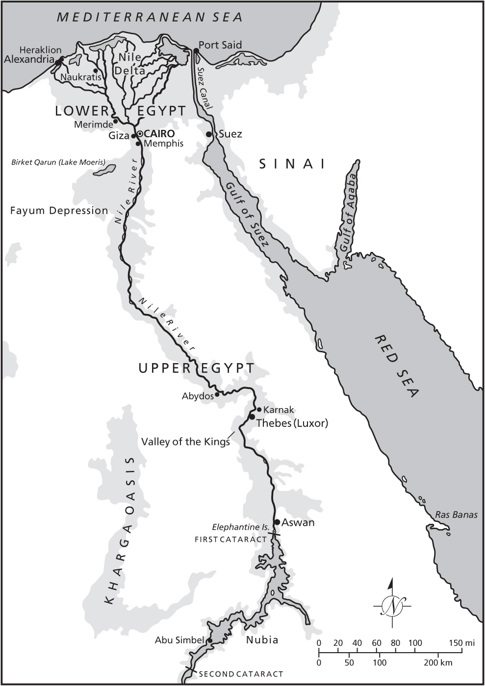

From the cataract, the narrow green Nile floodplain shoots like an arrow across the eastern Sahara Desert. It is as if ancient Egypt were a giant lotus flower. The stalk ran through the narrow valley that is Upper Egypt, then flowered into the blossom, the fan-shaped delta of Lower Egypt, known to the pharaohs as Ta-Mehu, “the flooded land.” (The Nile flows from south to north, which means that Upper Egypt is in the south, a confusing label for many people.) From an area near modern-day Cairo (a medieval Islamic city), the delta opens up dramatically into a featureless landscape. It is as if one is entering another country, which is why the ancients spoke of their state as formerly two lands. Close to the Mediterranean shore, the Nile dissolves into once-extensive marshlands and brackish lagoons, what the Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson calls “a shifting landscape, poised between dry land and sea.”

8

Here inhabitants once passed from village to village down narrow, reed-swathed defiles where bird life abounded and catfish lingered in the shallows.

The boundary between the Upper and Lower Nile was the area the ancient Egyptians called the Balance of the Two Lands, the place where the Nile splintered from a linear valley into myriad channels. The Balance became the administrative center of Egypt when the first pharaoh, Narmer, unified the Two Lands into a single kingdom around 3000 B.C.E. The pharaohs ruled their domains from nearby Memphis for three millennia. A line of royal pyramids at the edge of the desert extends almost thirty-two kilometers along the edge of the desert cliffs west of the ancient capital. Lest one wonders why the capital lay in the Balance of the Two Lands, consider this: Ta-Mehu has been Egypt’s granary for more than five thousand years. Today, the delta’s fields, two thirds of the country’s habitable lands, provide two thirds of the country’s agricultural output. Three thousand years ago, the pharaohs depended on the same acreage to feed their people, so they made sure their capital was close by. They were also well aware that Ta-Mehu was under siege from the Mediterranean, the northern frontier of their land.

Figure 3.2

The Nile valley.

THE NILE DELTA is one of the largest in the world. It covers some 240 kilometers of the Mediterranean shoreline and extends about 160 kilometers upstream to the vicinity of Cairo. This is an arcuate (arc-shaped) delta, like an upended triangle with an arc-like lower edge. The delta has always been vulnerable to rising sea levels, for it is a meeting

place between the land and the ocean. Today the outer margins of the delta are eroding in the face of destructive waves driven by the prevailing winds and winter storms of a rising Mediterranean. In places, the coastline is advancing as much as ninety-one horizontal meters a year. By 2025, experts project a sea level rise of thirty centimeters, which will inundate about two hundred square kilometers of agricultural land. The Nile delta is slowly becoming a salty wasteland, yet about half of Egypt’s eighty million people live in the general region, with rural populations alone averaging one thousand people per square kilometer.

For all its dense population today, Ta-Mehu is a geologically new land.

9

Eighteen thousand years ago, the late Ice Age Nile flowed into a Mediterranean that was much lower than today. Cores bored into delta deposits and the underlying bedrock tell us the coastline was at least fifty kilometers farther north than today. At the time, the Nile flowed across an alluvial plain dissected by numerous small channels. The faster-flowing river waters of the day deposited little silt on the plain. Had you visited the mouth of the Nile, you would have gazed across a gently undulating near desert, a sharp contrast to the lush floodplain of today. Your feet would have crunched on coarse river gravel brought down by summer floods. The Nile itself would have flowed vigorously down a steeper gradient than today. At flood time, some of the water would spill over into shallow depressions, where stunted grass would grow in the lingering damp. But the landscape would have been bleak and inhospitable, even at the shore, which was devoid of the lagoons and lakes that formed in later times.

After about 7500 B.C.E., sea levels climbed rapidly. An unstable, constantly changing shoreline migrated southward as the Mediterranean flooded broad tracts of coastal lands and deposited marine sand over a wide area. One would still have trodden on gravel rather than fine river silt, despite a shallowing river gradient. The coastline would still have been a desolate waste of sandy beaches and blowing dunes with no standing water except in the river and its side channels. The big change came around 5500 B.C.E., when sea level rise slowed, just as it did in the Persian Gulf. The now much more sluggish Nile ponded in the neighborhood of modern Cairo. Here, at the Balance of the Two Lands, the

stalk of the lotus—a relatively narrow valley—now blossomed into a broad delta, the flower of the long plant. As the ponding, and now much slower flowing, Nile deposited enormous quantities of silt along its course, the delta assumed its basically modern configuration. Now dozens of channels large and small carried the river to the sea. At flood time, the inundation spread over the delta, effectively waterlogging much of the land. Meanwhile, the Sebennetic channel of the Nile, in the western part of the delta, transported so much coarse sand to the coast that it formed an extensive sand barrier, a natural fortification against the rising sea. By now, tiny numbers of hunters and foragers must have settled the flat landscape, not so much the flatlands, but the extensive lagoons, lakes, and marshes that formed behind the shoreline. Here, as in southern Mesopotamia, extensive wetlands served as a magnet not only for small numbers of humans, but also for migrating waterfowl on the great Nile valley flyway. Rich in fish and plant foods, and also reeds for housing and canoes, the coastal waterways soon attracted hunters, and, shortly afterward, farmers and herders.