The Attacking Ocean (11 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Three quarters of a century ago, a charismatic British excavator, Leonard Woolley, spent twelve seasons from 1922 to 1934 excavating the ruins of the ancient city of Ur, biblical Calah, associated in the Old Testament with Abraham. Woolley excavated on a grand scale.

10

Hundreds of workers cleared overburden accompanied by lilting songs chanted by a Euphrates boatman recommended by his legendary foreman Sheikh Hamoudi, whose passions in life were said to be archaeology and violence. A decisive leader who was never at a loss, Woolley worked with only a handful of European colleagues, moving earth by the ton. He excavated the great ziggurat pyramid of Sumerian king Ur-Nammu, built during the twenty-first century B.C.E. and still towering above the ruined city. His men cleared entire city quarters, where Woolley delighted in showing visitors the cuneiform inscriptions set in the doorsills that identified their owners.

Figure 4.3

Archaeological sites mentioned in

chapter 4

.

This remarkable archaeologist became world famous for his excavation of the spectacular royal graves under the city, notably that of Prince Puabi. Woolley was a vivid writer, who brought the past to life with effortless panache—even if some of the details did not entirely match his observations. He described the solemn royal funerary processions, the ordered courtiers being handed clay cups and simultaneously taking poison to accompany their lord into the afterlife. Spectacular stuff by

any archaeological standard, unfortunately much of it unverified, for Woolley’s excavation notes are too incomplete by modern standards. But the royal graves momentarily paled into insignificance alongside the discoveries at the bottom of a deep pit sunk to the very base of the great city mound.

As part of his study of the chronology of Ur, Woolley had excavated a small mound called al-‘Ubaid about six kilometers north of the city. Here a previous excavator had found a very early temple built by Ur’s first Sumerian king that clearly merited further excavation. The new excavations probed a low tumulus about 1.8 meters deep some fifty-five meters from the temple. A small village—built on a low hill of clean river silt that stood above the floodplain—emerged from the mound, marked by hundreds of painted potsherds, the remains of small matting houses, and tools made of obsidian (volcanic glass), but no metal artifacts whatsoever. In the days before radiocarbon dating, Woolley could not date the village, but it was earlier than the Sumerian temple and anything he had so far discovered at Ur itself. He assumed that these humble farmers were the first inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia long before the first cities rose along the Euphrates.

After excavating al-‘Ubaid and the royal graves, Woolley turned his attention to the base of the Ur mound. A small test trench yielded ‘Ubaid-like potsherds on sterile sand underlying deep flood deposits. The thick zone of mud puzzled Woolley. His staff was also nonplussed. Then his wife, Katherine, came by. She glanced at the trench and remarked casually, “Well, of course, it’s the Flood.” In an era still somewhat obsessed with proving the historical veracity of the scriptures, Woolley had wondered the same thing, but “one could hardly argue for the Deluge on the strength of a pit a yard square.”

11

He returned in 1930 and sunk an enormous pit that went down nearly twenty meters to bedrock. The great trench yielded a stratified chronicle of ever-earlier settlement that had culminated in the early Sumerian city. First the diggers uncovered eight levels of houses, then the thick layers of a potting factory where the potters had discarded their “seconds” and constructed new kilns atop the broken vessels. Woolley

tracked the changes in pottery styles as the diggers went deeper. He started with the wares found in the houses, then the vessels from the potters’ precinct—plain red pots and vessels fashioned from greenish clay with red-and-black-painted designs, just like those from nearby al-‘Ubaid.

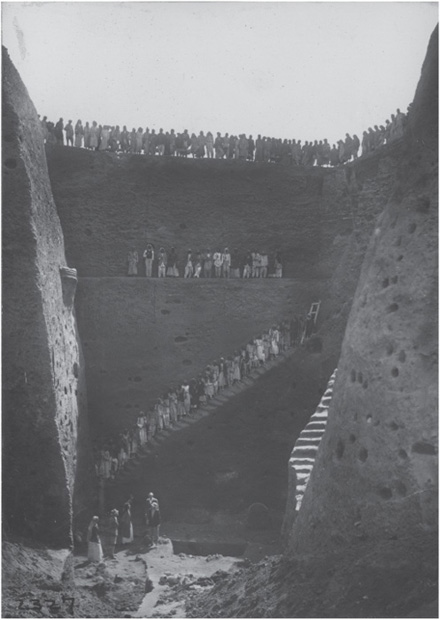

Figure 4.4

The so-called Flood Pit at Ur, excavated by Leonard Woolley. © University of Pennsylvania Museum.

Some of the owners of the red vessels lay in graves dug into sterile river silt under the potters’ workshop. The dig passed through nearly three meters of clean river silt deposited by the Euphrates. Below lay three superimposed levels of mud-brick and reed houses identical to those at the original al-‘Ubaid site. At last the excavators reached stiff green clay, once a swampy marsh—what Woolley called “the bottom of Mesopotamia.” Apparently the first occupants of Ur tipped their garbage into the marsh, built up a low mound, and then settled on it, inadvertently forming the core of a much later city.

The excavation of what soon became known as the Flood Pit at Ur gave Leonard Woolley a unique chance to exercise his fluent pen. With effortless imagination, he pulled out all his literary organ stops. Here, he claimed, was not only evidence of a great flood then popularly associated with the Garden of Eden but also archaeological confirmation of the great inundation described in Assyrian and Sumerian epics preserved on clay tablets. The ‘Ubaid people of preflood times had not been obliterated by the biblical deluge, but had survived the waters to plant the seeds of Sumerian civilization. “And among the things they handed down to their successors was the story of the Flood … for none but they could have been responsible for it.”

12

Even Sumerian king lists spoke of rulers who reigned before and after what must have been an epochal flood, even if it was not the one in the scriptures.

The silt deposit was deepest on the north side of the city, where the mound had broken the force of the inundation. He estimated that the flood covered an area at least 480 kilometers long and 160 kilometers across, destroying hundreds of villages and small towns. Only the oldest cities were safe on their ancient mounds. The disaster must have been catastrophic and endured in human memory for generations. “No wonder that they saw in this disaster the gods’ punishment of a sinful generation and described it as such in a religious poem.”

13

The Flood Pit with its evidence for a huge inundation caused an

international sensation at the time, overshadowing similar flood deposits found elsewhere in the depths of other city mounds. Today both archaeologists and linguists doubt that the Ur floods, or any others for that matter, were the source of Mesopotamian flood narratives. They think they are merely evidence for endemic, sometimes catastrophic inundations in the flat terrain of southern Mesopotamia, where the gradient of the flood-plain changes by a mere thirty meters over seven hundred kilometers.

Today, prosaic finds like stone artifacts and characteristic greenish, painted ‘Ubaid pottery like that from Ur document a far-flung, simple farming culture that flourished over a wide area of southern Mesopotamia. Upstream of the wetlands and marshes, the landscape gave way to arid terrain, where human settlement clustered near major watercourses and on levees and natural ridges that became islands when the floods came. Nearby marshes and wetlands with their abundant plants, wildlife, and fish served as anchors for many early farming communities, such foods being the fallback when fast-running water swept away growing wheat and barley before being absorbed by the spongelike reeds and swamps of the lower delta.

This insurance worked well, for within two thousand years or so profound changes were under way in southern Mesopotamian life. The Gulf was retreating slightly; life-sustaining marshes with their vital food staples may have proliferated as freshwater wetlands replaced brackish lagoons. From the earliest days of farming, people living by the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers had diverted floodwaters through narrow furrows onto their small fields, lying strategically close to side channels. Barley and wheat grew well in the fertile soils and the floods of early summer came at a critical moment for the growing crops. As the centuries passed, small clusters of reed dwellings became larger, more permanent communities built on levees and low ridges. Hamlets coalesced, then turned into larger villages and small towns, clustered around shrines to patron deities, just like the humble settlement on the low mound at al-‘Ubaid near Ur. No one living in these growing communities had any illusions about the risks of farming in an environment where the capricious rivers nearby could flood and wipe out generations of close-set houses in a few hours, then change course without warning.

A combination of irrigation and food from marshes worked so well that some of the larger towns became the world’s first cities. Uruk was the home of the mythic Gilgamesh, hero of the epic that bears his name, and one of the earliest cities on earth. The city’s weathered mounds lie in an arid landscape east of the present-day Euphrates, on the banks of the now-dry but ancient Nil Channel, which provided both irrigation water and access to trade routes up- and downstream. Canals separated Uruk’s bustling neighborhoods, so much so that some imaginative modern observers have called Uruk the Venice of Mesopotamia. According to the

Epic of Gilgamesh

, Uruk had three segments, “one league city, one league palm gardens, one league lowlands, the open area(?) of the Ishtar Temple.”

14

The city originally came into being when two large villages merged into a single settlement around 5000 B.C.E. Serious growth began a thousand years later, when crowded neighborhoods of small houses clustered around major shrines. By 3500 B.C.E., Uruk was much more than a large town. Satellite villages, each with their own irrigation system, extended as much as ten kilometers in all directions. Uruk and its temples had become a major trading center, linked with communities near and far by trade that moved up and down the great rivers. However, throughout its life, the thriving city relied on the nearby marshes, which figured prominently in incantations and myths, for it was from the reeds that the god Marduk had created the first dwellings in this violent land:

Marduk laid a reed on the face of the waters,

He formed dust and poured it out beside the reed.

That he might cause the gods to dwell in the habitation of their hearts’ desire.

15

These reeds would never have grown had it not been for the rise and fall of the Lower Sea to the south.

Distant, unseen forces governed the fate of Sumerian cities. For thousands of years, rising sea levels downstream rendered much of the flat landscape south of Ur unsuitable for human habitation, except where natural ridges lay above flood level. Then the Gulf shoreline retreated significantly after 4000 B.C.E. Marshes formed and became an anchor

for human life, while the rivers remained an unpredictable force. Both the Euphrates and the Tigris meandered over the landscape in broad loops and sometimes changed course when they burst their banks during major floods. The Euphrates has shifted its lower reaches time and time again without warning, transforming both natural and humanly altered landscape in fundamental—sometimes catastrophic—ways. Each village and every city faced a daunting landscape that could change in days. No river channels in southern Mesopotamia were permanent. One rapid shift saw the Euphrates redirect its course abruptly from east of the growing city of Nippur to much farther west, leaving the city literally high and dry. Uruk suffered greatly when the Euphrates shifted eastward from a line through the city to a more easterly course that favored another urban center, Umma.

All of this made for a volatile political and social environment and for haphazard settlement patterns that followed elongated levees along major channels and minor ones that ran parallel to the main channel. Mesopotamia was a volatile, ever-changing landscape, whose configuration changed with rises and falls in Gulf sea level and with the severity of river flooding. This helps explain why Sumerian civilization was a jigsaw of intensely competitive city-states, each with its own hinterland of villages and irrigated lands, and completely dependent on the vagaries of the natural environment and the ocean that lay far over the horizon.