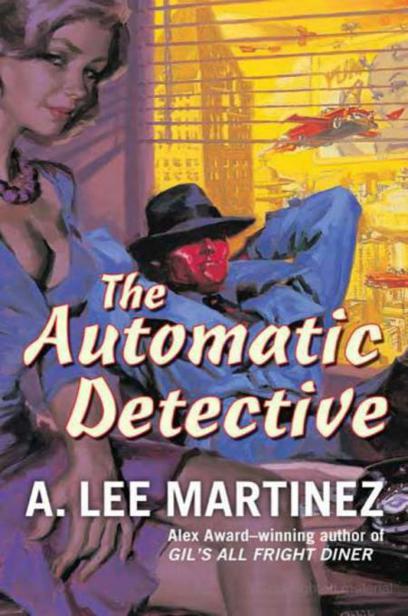

The Automatic Detective

Read The Automatic Detective Online

Authors: A. Lee Martinez

The Automatic Detective

Tor Books by A. Lee Martinez

Gil's All Fright Diner

In the Company of Ogres

A Nameless Witch

The Automatic Detective

A. LEE MARTINEZ

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed

in this novel are either products of the author's imagination

or are used fictitiously.

THE AUTOMATIC DETECTIVE

Copyright © 2008 by A. Lee Martinez

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book,

or portions thereof, in any form.

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

For Mom, thanks for helping bring my genius to the world

For the writers of the DFWWW, for always recognizing

my astounding talent, criticizing my lousy writing,

and just generally putting up with me

And for Zarkorr the Invader . . .

CITIZENS OF EARTH, BEWARE

!

The Automatic Detective

The Learned Council had an official name for Empire City.

Technotopia.

Yeah, it wasn't a real word, but that was kind of the point. The Council loved to reinvent things, improve them, make them new and snazzy. Of course Empire had a lot of unofficial nicknames as well.

Mutantburg. Robotville. The Big Gray Haze. The City That Never Functions.

But Technotopia was the official party line, along with the motto "Building Tomorrow's Town. Today." I guess it all depended on what you thought the future should look like. If you were looking for a bright and shiny metropolis where all of civilization's problems had been solved through the wise and fortuitous applications of equal parts science, wisdom, and compassion, then I guess you'd be out of luck. But if your ideal tomorrow was a sprawling, impersonal city with rampant pollution, unchecked mutation, and dangerous and unreliable weird science, then I guess you would be right at home.

Name's Mack Megaton. I'm a bot. Or automated citizen, as

the Learned Council liked to phrase it. There were three classes of robot in Empire. You had your drones: low sophistication models geared toward mundane tasks. Then there were the autos: humanoid models designed for more complex work. Then you had your bots: autos and drones that qualified for citizenship. I hadn't quite reached bot status yet, but so far my probation had been going smoothly, and I was only forty-six months, six days, four hours, and twenty-two minutes from crossing that objective. I occupied a more vague class between auto and citizen. I couldn't vote, couldn't hold public office, and if the Learned Council decided to issue a recall, there wasn't much I could do about it.

I was barely two years old and weighed a compact seven hundred and sixteen pounds. That's light when you're seven feet tall and made entirely of metal. I could punch through concrete and bend steel. I could not, however, tie a bow tie. My programming was state of the art: adaptive, intuitive, evolutionary. I wasn't programmed knowing how to drive a cab, and I got along just fine doing that. I wasn't designed to play poker, and I was a decent card sharp, though it's easier to bluff when you have a featureless faceplate. But my artificial intelligence couldn't wrap its binary digits around the ins and outs of getting a bow tie on. My hands didn't help any. They weren't designed for delicate work, more like sledgehammers with fingers. But the Bluestar Cab Company insisted all its drivers wear bow ties. Real, honest-to-God bow ties. No clip-ons. That's what got me involved in the mess.

A bot's got bills to pay. Bill, really. I used to be juiced by a small atomic power core. That was gone now. The Learned Council removed it as part of the terms of my probation. But I still consumed a lot of electricity in a day, and it didn't come cheap. Not in Empire. There was barely enough to go around in this town. To get my fair share to keep up and running costs

plenty. It was fortunate that I didn't have many other expenses or I'd have never been able to support myself driving a cab. As it was, I usually had to operate at half-power. Used to feel sluggish doing that, but I'd gotten adjusted to it.

So every morning at the end of my recharge cycle, I'd get shined up and dressed for work and head out the door. And along the way, I'd stop by my neighbor's apartment and have Julie wrap that tie around my barely existent neck. She didn't mind. She was the nicest, warmest person I'd met in Empire. Every time I scanned her, I was always glad I hadn't gone with my original program and led that robot army.

She was always expecting me, usually already waiting with a smile and a friendly word. Today, she wasn't. No big deal. Probably just busy. Those two kids were a handful sometimes. And her husband wasn't much help.

I knocked on the door. No one answered. My internal chronometer counted off sixty seconds before I knocked again. It was another thirty-six seconds before the door slid open and Julie stuck her head out. By then my intuition simulator started beeping. When that little ping went off in my right audio sensor, it usually meant trouble. I couldn't turn the damn thing off, so I did my best to ignore it.

"Mack." She looked surprised to see me. "Oh, Mack, I'm sorry. I forgot."

She slid the door wide enough to step out and shut it before I could catch a view inside. She snatched the bow tie from my large metal hands and started to tie it. She fidgeted a bit, glanced back at her closed door.

"Everything all right, Jules?" I asked, despite my better judgment.

She laughed, trying to pass it off as casual, but it came out anxious. "Oh, everything's fine, Mack. Thanks for asking."

I was pretty good at reading people. I had a peachy little

voice and body language analyzer subroutine that rarely failed, but I didn't need it for this because Julie was a bad liar.

I'd done my part. I'd asked. It wasn't any of my business now. Probably nothing serious anyway. Stress is stress. The biological body reacts the same way no matter the source, whether being chased by a bear or in the middle of a domestic tiff. Julie and her husband fought a lot.

But Julie always smiled for me. Always. She was smiling now, but it wasn't the same. My analyzer didn't bother spelling it out to me, but it encouraged that pinging in my audio to get louder.

"There you go, Mack. Sorry, it's a little crooked, but I'm kind of busy right now."

"No problem, Jules. Thanks."

"Sure." Another furtive glance at that door. "Have a great day."

I was about to return the sentiment but she disappeared into her apartment before I got the chance.

"Mind your own business, Mack," I said.

Talking to myself was a bad habit. You'd be surprised at the extraneous behaviors that make it into your personality template when you hang around with biologicals. My intuition must've caught the hint though, because it stopped beeping.

I adjusted my tie, careful not to loosen it or else I'd have to knock on the door again. I wasn't built for stealth, and the strange yellowish metal they use for flooring in the cheaper apartment complexes squeaks when I walk on it. Despite the noise and my stalwart vow to keep my nose clean (which should have been easy since I didn't have a nose), I heard something break in Julie's apartment. A plate or piece of glassware falling off a table. Nothing serious.

I stopped, cranked my hearing to the max. My audio array

isn't much better than human hearing, but I've got a directional mic. It doesn't penetrate steel doors. Everything in Empire, even the doors, was made of metal.

Muffled voices. Julie's. Gavin, her husband. Holt, one of the kids. Somebody else I didn't know. Another round of shattering glass. And another. Then a stifled scream. The wet slap of meat hitting meat, somebody getting hit. Crying.

My intuition simulator didn't fire up again. No need for it. I didn't need a ping to tell me there was a problem.

Consciousness is a quagmire, whether found in squishy organic tissue or an interminable string of squirming electrons. I don't know where logic is found in the human brain, and I don't understand the inner workings of my own electronic brain either. It's dozens upon dozens of programs interacting, prioritizing, compiling, doing lots of other technical stuff. Somewhere in my common sense replicator, in that ricocheting string of ones and zeroes, there must've been a digit missing, and as I moved back toward Julie's apartment, I cursed Professor Megalith for not spending more time in beta testing.

I knocked. It got quiet inside real fast. The door slid open. Julie stuck out her head.

"Is everything all right, Jules?" I asked again.

She answered the same way. "Yeah, yeah. It's fine."

"How's Gavin?"

"He's fine."

We didn't say anything for a bit (four seconds for those of you without a built-in clock), but I could record crying still coming from inside. April, their daughter: one of the top voices in my recognition file. Hearing her sob quietly made me glad I was doing this. But what was I doing?

"It's not a problem, Mack," said Julie. "Thanks anyway."

Empire was a progressive town. It's the only city in the

world where a robot could earn full citizenship rights. But I was built for world domination, and I couldn't blame the authorities for wanting some time to see if I was truly interested in reforming. I had another four years probation left before the law considered me safe enough for citizenship consideration. If I blew it, there'd be no place left for me to go where I wouldn't be just another piece of property, an unlicensed weapon with a mind of its own, headed for the scrap heap.

If I barged into that apartment, I'd blow it, but if I wasn't going to follow through, I shouldn't have come back in the first place.

Julie tried to slide the door shut, but I thrust my hand against the jamb. I didn't ask to come in. I pushed it open and stepped inside.

The apartment, like 92 percent of all apartments in Empire, was one room partitioned into various areas. Except the bathroom, which was a metal box (always metal) in the corner about the size of three phone booths put together. It didn't take long to sweep the place with my opticals and see the problem. It wasn't Gavin, as I'd first assumed. He slouched in a chair. He held a hand clamped over his mouth, and blood dripped down his chin. I spotted broken dishes and the remains of half-eaten breakfast scattered on the floor along with two teeth. Gavin's, I assumed.

The kids were huddled in a corner. They were both mutants. Few people were born mutated in Empire. It was more often something that just happened one day. There were a lot of strange chemicals in Empire's waterworks, weird radiation pockets hovering in its streets, and unstable mutagenic gases floating invisibly in the air. On any given day, every biological citizen was subjected to dozens of genetic destabilizing agents, and every citizen knew that they might sprout a third eye or grow tentacles at any moment. There didn't seem to be a pattern

to it, and your social status, the size of your bank account, none of that mattered.

Of the two Bleaker kids, Holt was the more obvious mutant. He had scales and a long tail. Nothing too serious. Mutation was acceptable in Empire, even commonplace, and while the rest of the country was working out issues based on hereditary pigmentation, Empire had moved well past such noisy debates. It was just impractical to argue when the only real difference between a norm and a mutant was one unpredictable genetic reaction just waiting to happen.