THE BEAST OF BOGGY CREEK: The True Story of the Fouke Monster (15 page)

Read THE BEAST OF BOGGY CREEK: The True Story of the Fouke Monster Online

Authors: Lyle Blackburn

It was true about the two couples moving into the house. One couple was Don, our four children and myself. The other couple was Charles and Elizabeth Taylor. They had no children. At the time she was pregnant. The first night we stayed there we don’t know who or what was fooling around the house. We did take the children and go across the highway to our neighbor’s house, not the landlord’s because he lived about 3 or 4 miles from us.

Bobby and Corky Hill did come to spend the weekend with us. They went to the creek to fish, but never did because they found the footprint [

12]

as soon as they got there. That night we had a visit from the Fouke monster. Don and Charles were not at work, they were there. The thing was either awfully smart or there were two of them because it would lead Don and Charles away from the house and before they got back it would already be there.

They did go to the constable’s home after a gun and then he brought another one. The bathroom scene was true except Bobby ran into the living room instead of the bedroom.

When the hand came in the window, it was Elizabeth who was sitting there on the couch. Bobby was sitting in the chair holding a butcher knife. When he saw the hand, he grabbed Elizabeth and threw her on the floor.

The rest was true until the part where Bobby went all the way through the door. He didn’t. He ran around the porch to the front door and just as I was about to open the door for him, he stuck his whole arm through the glass part of the door.

We did go back to the constable’s house when Bobby was in shock but no one laid a hand on him except Don. Bobby kept coming to on the way to the hospital. He was screaming and trying to kick out the car windows so Don would knock him back every time he came to. We had no police escort either. We escorted ourselves to St. Michael’s Hospital by blowing the car horn and running every red light from Fouke to St. Michael.

There you have the story as it happened. The Texarkana law did go out to the house with guns and look around but they couldn’t find anything. It seemed to us that the thing was after our dog because every room our dog went into was where the thing tried to get in next.

Although Mrs. Ford’s account may be more accurate in terms of the chronology of events, whether or not Bobby jumped through a screen door or shoved his hand through some glass, and whether they had a police escort or not, the fact is that the families experienced something very strange. They still believed a seven-foot hairy creature had visited their home on possibly more than one occasion, not to mention that they fired guns at the creature and

something

stuck a hairy hand or paw through the window. Despite any liberties Pierce took in the pursuit of entertainment, there is no denying the fact that something mysterious lurked in the culture, conscience, and surrounding countryside of down-home Arkansas. Now that something was about to experience its very own permanent cinematic legacy.

Four-Wall Phenomenon

Once the raw movie was in the can, as they say in the business, Pierce packed it into his car and headed to Los Angeles. Mr. Ledwell had reached his monetary limit—roughly $100,000—at that point, so if the movie was going to be completed with editing and soundtrack, Pierce would need the help of someone willing to cut him a deal. He didn’t have any Hollywood contacts, but after asking around, Pierce was put in touch with Jamie Mendoza-Nava, who owned a small post production house. Mendoza agreed to finish the movie without much cash up front, if Pierce would pay the fee for his editor and agree to give Mendoza a small percentage of the royalties.

Recognizing a fair deal—and his only option, really—Pierce turned the project over to Mendoza. The raw film was then edited by Tom Boutross (who had previously cut the classic horror film,

The

Hideous Sun Demon

) while Mendoza composed the soundtrack. In a short time, Pierce was the proud owner of a completed movie.

The next step was to find a suitable distributor. But, as expected, an independent filmmaker from Arkansas shopping a “Bigfoot” movie was not going to receive a red carpet welcome at any Hollywood studio. And, in fact, for a while it seemed he would not get so much as a bathroom rug to step on. He was repeatedly hung up on or laughed at by studio reps. Or he was told that he would need an agent to submit the film.

So Pierce needed another plan. Not only did he believe in his film, and was not a man to give up easily, but he owed Mr. Ledwell a rather substantial sum. Ledwell had been calling nearly every day to find out if he had any luck selling the film. Things were not looking good. So Pierce drove back to Texarkana and promptly headed to an abandoned, run-down theater. If nobody in Hollywood was interested, then he would just show the movie himself. In his

Fangoria

interview, Pierce said: “I went to the old Paramount Theater in downtown Texarkana. I went in, and I saw that the projectors and stuff were still there. I talked to an old projectionist, and he said, ‘Oh yeah. They’ll run.’ So I called the company that owned the theater and asked if I could use it to have a world premiere. And they said, ‘Well, Mr. Pierce, we’ll sure

rent

you that theater.’”

Pierce convinced Ledwell to cough up $3,500 to rent the theater for one week and hire all the necessary crew including ticket-takers and a projectionist. This self-driven process was not common, but some, like Sunn Classics, had gone this route in order to play its low budget films. Known as “four-walling” (i.e., renting the entire theater to the “four walls”), Sunn had ironically done this a year earlier in order to market

Legend of Bigfoot

, a pseudo-documentary produced by famed cryptozoologist Ivan Marx. In fact, Pierce cites

Legend of Bigfoot

as having an influence on his own movie.

Since the theater hadn’t been used for some time, Pierce and his crew had to literally hose down the floors and clean it up themselves. Nerves ran high. Would all their hard work pay off? Or would the film flop? But just one look around the block outside the theater on opening night was sufficient to answer that question. The buzz the Fouke Monster had created in the newspapers just a year earlier would have no problem in carrying over onto the big screen.

The movie premiered on August 18, 1972. Pierce sums up the excitement: “There were people lined up for four or five blocks. People had brown-bag

lunches

with ‘em because they knew they couldn’t get into the next showing, but they didn’t want to lose their place in line. I knew it was gonna work when they started laughin’ and getting excited, and screamin’ whenever that booger’d jump out…. I got a G rating, and so the kids were in there screaming—it was scarin’ the

devil

out of ‘em. I knew then I had a winner.”

In no time, Pierce pulled in enough cash to double his efforts. He took his only other print of the film, which was actually a reject copy, and began showing it in another rented theater in Shreveport, Louisiana. It was a hit there, too. Then came the calls from Hollywood studios, realizing they had bet on the wrong horse… er, monster. But they mostly wanted to “test” the movie in other markets without paying any money up front. Pierce wisely passed and continued to four-wall his own showings. It didn’t take Pierce long to pay off Ledwell, Mendoza-Nava, and others who had kindly fronted the expenses, but so far he hadn’t seen much return for his own investment of time and effort over the previous year. That changed dramatically, however, when he struck a deal with Howco International, a successful regional distributor.

Pierce asked for one million dollars (plus money to cover taxes) for a 50 percent interest in the movie. Howco balked at first but soon made Pierce’s dream of becoming a millionaire a reality with one monstrous million dollar check. With a proper distributor, Pierce worked closely with Howco to promote the movie, transforming it from a four-wall phenomenon to a certified national sensation that played in theaters and drive-ins across America. Pierce was also able to cut a deal with American International Pictures (home of the low-budget cinema mogul, Roger Corman) to bring

The Legend of Boggy Creek

, and awareness of the Fouke Monster, to audiences worldwide.

The film was a remarkable success, going on to gross more than $25 million dollars, a figure backed up by notes in Pierce’s own papers and verified by his daughter Amanda. Some claim the movie made upwards of $100 million, but $25 million is the official mark. It’s certainly an amazing outcome for a first-time director who depended on volunteer help, civilian actors, and his own ingenuity to make it happen. And it was something the little town of Fouke could be proud of, right?

Wrong.

The Aftermath

The timing could not have been better for

The Legend of Boggy Creek

. It was a time in the 1970s when interest in Bigfoot was on the rise and the media did not have such a cynical view of the unexplained as they have today. Despite the G rating, Pierce’s docudrama style managed to not only scare the moviegoers, but to blur the line between the real and the sensational aspects of the subject matter. This resulted in fevered reactions ranging from real fright to all-out Fouke Monster mania.

Once again people began to descend on Fouke like wolves on a rabbit feast. The curious now came from

hundreds

of miles around, not just regionally, in hopes of either spotting the monster, having a look at houses shown in the movie, or to hunt the monster itself, as many locals had done a few years earlier. It was a flashback to the chaos incited by the radio station reward of 1971, but this time the craziness was even worse. As they did during the previous invasion, town officials forbade hunters to take guns into the woods to look for the monster except during deer season. It was all they could do.

New, larger bounties were posted. On September 16, 1973, the Texarkana-Arkansas Jaycees offered a whopping $10,000 reward for the capture of a live monster. The story ran in newspapers as far away as Victoria, a small town in south Texas. As expected, this drew even more hunters to Fouke, many of whom had shotguns perched in their truck’s gun racks and dollar signs in their eyes.

Letters deluged the town, adding postal employees to the list of annoyed locals. At one point the Fouke Mayor’s office had a bundle of nearly 800 letters asking about monster hunting. One letter read: “We have seen a movie… and would like some information on the Boggy Creek monster as well as some information on the country you are in.” Another added a sense of urgency: “We are interested in receiving all information that you could possibly send us concerning the creature there in your area. We feel that this is very important to mankind.” Some letters were addressed to the Fouke Monster itself!

With the new wave of tourists, a few townsfolk recognized the opportunity and unveiled some sophisticated merchandising. Bill Williams, the new owner of the Boggy Creek Café, added several items to the menu such as the “Three-Toed Sandwich” and the “Boggy Creek Breakfast.” Willie Smith went further by manufacturing an unbelievable selection of money clips, cards, key chains, ash trays, bumper stickers, license plates, and other items engraved with “Home of the Fouke Monster.” He sold these out of the café and his gas station next door. Smith’s son, Monroe, later remarked that he was getting more questions from tourists about the monster than gas sales.

Smith also whipped up a new batch of his famous three-toed casts. These casts are now considered collector’s items in the cryptozoology community, since the originals were lost forever when the café burned down in the late 1970s. If anyone still has a first generation copy of the cast, especially if it’s signed by Willie Smith and Smokey Crabtree, you’ve got a genuine treasure on your hands!

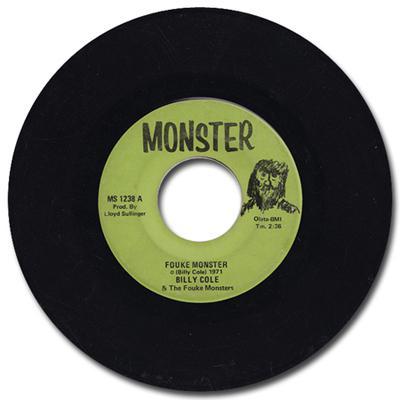

Jane Roberts, the wife of future mayor Virgil Roberts, also got in on the hype by creating her own miniature footprint replicas. She reportedly manufactured 5,000 copies, complete with a hand-painted “Greetings From Boggy Creek” message, and sold them to outside distributors for 50 cents each. A 45-RPM vinyl record was released, featuring a song called “Fouke Monster” by Billy Cole and The Fouke Monsters. The song, commissioned by Pierce as movie advertising, sounded like quirky 60s-era rock with a spooky chorus that chanted “Monster, Fouke, Monster, Fouke, Monster.”