The Beckoning Silence (15 page)

Read The Beckoning Silence Online

Authors: Joe Simpson

Tags: #Sports & Recreation, #Outdoor Skills, #WSZG

‘Will it affect my modelling career?’ he asked as she pushed him into a cubicle.

‘I’ll see you in the bar, Ray.’ I called after him and then smiled at the receptionist. ‘He’s very, very stupid, I’m afraid,’ I said loud enough for Ray to hear. ‘It’s congenital, you see,’ I added and she smiled at me warily.

He appeared at the bar an hour later proudly displaying the bristling line of stitches in his cheek.

‘It cost four hundred bloody dollars,’ he complained bitterly.

‘That’s American health care for you.’ I peered at the stitches. ‘Looks like they’ve done a good job. You’ll hardly see the scar in a year or so.’

‘Listen, I’ve been thinking,’ Ray said. ‘Maybe we should try another route. Get a bit more ice climbed before we go back to Bridalveil.’

‘Oh, good,’ I brightened up. ‘I was worried that you might have been put off it altogether.’

‘No way,’ Ray said sharply. ‘I’ve got a bone to pick with that bugger now.’

The following day we climbed the Ames Ice Hose. The last pitch was melting furiously. Of the six ice screws I placed on lead all but the last one had melted out by the time I had reached the top and Ray had only to pluck them from the ice with his fingers.

The Ames Ice Hose proved to be one of the finest ice climbs I had ever enjoyed, varied, sustained and challenging. Indeed we climbed it in such fine style that our confidence came surging back after our setbacks on Bridalveil Falls.

Early the following morning, nursing Ames Ice Hose celebration hangovers, we tramped wearily back up to the Falls. A light snow was dusting the air and it was freezing hard. For once there were no other parties on the climb. We could now make idiots of ourselves in peace.

Ray climbed swiftly back to the blood-spattered cave and set up a solid belay from which I led up a steep ice pillar to a solid belay on ice screws and threaded icicles just to the left of the central overhanging band of cauliflower ice. ‘Don’t worry, I’m right behind you,’ he said with a grin as I made the first tentative swings of my ice axes. After about 15 feet I found myself braced across a groove between two vertical ice pillars with my arms tiring rapidly. Ray was out of sight hidden safely beneath the overhanging start to the pitch. My breathing became a little ragged as I struggled to place an ice screw in an awkward spot between two hollow icicles. An awkward swing to the right around the pillar led into a confused area of bulging leaves of ice. It pushed me off balance, forcing me to hang free on my arms from my axes as I tried to work out the best way forward.

A solid axe placement high and to my right enabled me to pull myself up to a point where I could lock my right elbow. I instinctively pushed the elbow out to my right. In an instant it had slid behind an adjacent leaf of ice and by pressing outwards I found that I could hold myself easily in balance. When I made the same move with my left arm I found myself perched on the overhanging ice with both elbows shoulder high at right angles to my body jammed behind convenient slivers of ice.

Good God!

I thought.

I’m chicken-winging. So that’s what the guy was on about.

It was an astonishingly stable and restful stance despite the spectacular position in which I was poised. I let out a whoop of glee and Ray called up to ask me if I was OK.

‘Fantastic,’ I yelled. ‘Bloody superb.’ I looked above me and was disappointed that there was not the second band of overhangs that form in some years. Until that point the very prospect of such an increase in difficulty had filled me with dread. I knew that having overcome the first band of overhangs it would be extremely difficult if not impossible for me to retreat. Yet now I was looking forward to finding the way ahead blocked by another seemingly insuperable barrier. I knew I would be able to climb it with ease. So long as it was water ice, I felt sure I could climb 6+, even grade 7. It wasn’t vain boastful pride; it was simply true. I had learned that I was better than I had thought, at least on that day and at that time, and it made me feel wonderful. I knew then that we were going to succeed.

It was not about being a ‘hard’ climber, not a challenge to prove to others how good we were, but a pure and simple test of ourselves. That moment when I knew I was strong enough and powerful enough, mentally and physically, to overcome the obstacles in front of me came as a rushing exultation, a joyous realisation that this was why I was here. George Mallory once wrote after succeeding on a climb, ‘We’re not exultant: but delighted, joyful: soberly astonished … Have we vanquished an enemy? None but ourselves …

’

I was meant to be there.

This is who you are; why you do this,

I thought, and grinned broadly all the way to the top of the pitch, delighting in the intricate mixture of power and subtlety, the delicate balance between gymnastic dance and thuggish strength. I became entranced, absorbed in the game of reading the ice. The feeling of invincibility was infused with the wondrous irrationality of what I was doing – immutable, anarchic living, the essence of climbing, of simply being.

Whether it was on a towering granite headwall, a Himalayan behemoth, an Alpine north wall, or a fragile lacy confection of towering water ice, the feeling was the same.

All my depressed thoughts had become meaningless. There was only one reason for my being there – to climb into the unknown, pushing my limits to discover how far I could go. I knew it would fade rapidly once the climb was done, and I wanted to luxuriate in the feeling. I hadn’t felt like that for a long time. I had missed it.

The outcome needed to be uncertain, the prospect frightening, the potential for injury high, otherwise there would be nothing learned and nothing proved. I didn’t want to die but if death hadn’t been ever-present then I doubt I would have been there. It set the parameters of the game. What we stood to lose was everything. We were fugitives from reality and yet things never seemed so real, so clear and sharp and right.

When I reached the belay cave near the top of the Falls I fixed three solid ice screws and shouted down to Ray that I was fine and he could come up. I leaned back on the slings and looked out over the plunge of the frozen ice falls. The snow had cleared from the air. Telluride lay huddled in the valley far below. The air had a bright translucent quality, a tangy, crisp perfection, cool on the lungs. The clean, gin-clear winter sky had an almost solid feel to it, like a polished wine glass that you could reach out and ping with your finger. I pulled hard on the ropes as Ray began to move, slow and stiff from his long wait beneath the icy overhangs.

I looked at the main stream of the waterfall plunging into space in a rushing white stream, ice crystals glinting in the afternoon sunlight and clouds of steamy vapour blowing back into the sky. I listened to the calculated dissonance of the thundering water as it rose and fell in swells of sound like a heavy symphonic weltering sea, so resonant that the crashing of the water in the plunge pool was a memory of the oceans with the surf calling its crying song. I wondered why we had ever been menaced by the sight of it and not transfixed, mesmerised by its beauty as I was now. Part of me knew that I was seeing with exultant eyes deceived by the chemical rush of excitement. But it was true for the moment and I would happily accept it as such.

Soaking up the spectacle, enjoying the experience of being there, happy and alive, reading it in my mind in a tumble of breathless metaphors, I tried to capture it in my memory for ever. I knew it would fade. It always did and the thought saddened me. What a strange, inexplicable misfortune it is, to come to this edge of perfection and then let it slip through your fingers.

I wanted to hold the moment for as long as possible before the inevitable lurch back to grey reality. The French have an expression for feelings such as these,

le petit mort,

the little death. The post-coital depression, the fleeting saddening loss when it is over. It seemed about right to me then. The bitter-sweet, heady ache of ecstasy and loss. The half-lost, half-won game of life that we could never quite finish. It seemed, sometimes, fleetingly, you could come close to the ineffable edge of perfection when it all goes to glory for the briefest of moments, an inarticulate moment, that leaves you with a vulnerable shattered sense of wonderment. It was life enhancing: pure emotion.

The ropes jerked tight in my hands. Ray had fallen off. I glanced down and saw him swing out from the overhangs with an expression of alarm and irritation on his face. The ropes slackened. He was climbing again. I was laughing at the fun of it all and the memory of his surprised dismay. He had been rushing the pitch, hooking his axe picks into air bubbles rather then smashing them forcefully into the ice.

Again the ropes went tight as one of his lightly hooked picks popped out of the ice, and I heard a stream of curses above the roar of the falls. He swung out into space in a gentle pendulum and his oaths swung out on the wind with him. I laughed again and shouted friendly insults into the winter sky.

Ray arrived in the cave breathless and smiling broadly. I knew how he felt. I clapped him on the back, and squeezed his shoulder and grinned happily at him but we did not hug. That was what Tat had been good at.

As we stumbled down the path in the gathering dusk we chatted excitedly about the climb, wondering at the audacity and skill of Jeff Lowe and Mike Weiss in attempting the climb nearly a quarter of a century earlier.

‘You know your idea about tick lists?’ Ray asked as we trudged down towards the car. ‘What do you have in mind?’

‘I’m not sure really. It was just an idea I had. You know, do a few classic lines, fill in the holes in my climbing CV before giving it all up.’

‘Do you still want to do that?’ Ray asked. ‘After this?’

‘Yeah, I think so,’ I replied and stopped to look at Bridalveil rearing up at the head of the canyon. ‘It was good, wasn’t it?’

‘Superb,’ Ray said quietly.

‘It would be nice to leave it like that, wouldn’t it?’

‘Yeah. I suppose it would,’ he agreed. ‘But it would be nice to keep doing it.’

‘I know, but it has to end some time,’ I said. ‘And I’d like it to be on my terms.’

‘Like Tat, you mean?’ Ray said and laughed softly.

‘Yeah, like Tat,’ I said quietly. ‘He was right you know. He just got unlucky.’

‘OK, so what about this tick list then? Any more cunning plans up your sleeve?’

‘Maybe The Nose or Salathe?’

‘Yes, that would be good,’ Ray said. ‘I’ve never been to Yosemite. And it would be warm …’

‘I suppose so,’ I said. ‘Still we’ll never stop if we don’t get a final short list. And I mean short.’

‘OK, so Bridalveil was one of them. The ice climb. Salathe or The Nose would be the rock climb on the list. We need a mountain route. A real classic. What do you think?’

‘A new route somewhere, perhaps,’ I said doubtfully. ‘I’ll think on it.’

‘Yeah, me too,’ Ray said as we reached the car. ‘Come on, let’s go drink beer. We deserve it.’

Joe cutting loose on Quietus Stanage Edge, Derbyshire

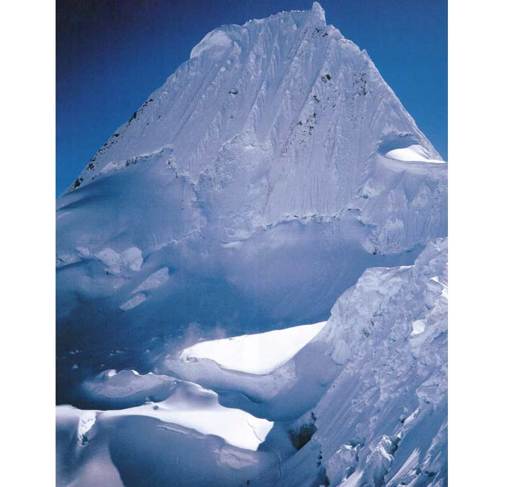

Ian Tattersall on the summit of Alpamayo

A ghostly face in the ridge watches over climbers following our tracks on Alpamayo