The Beckoning Silence (30 page)

Read The Beckoning Silence Online

Authors: Joe Simpson

Tags: #Sports & Recreation, #Outdoor Skills, #WSZG

Anna had brought them suddenly to life and given us a melancholy sense of how much they had lost. When she spoke of their long-drawn-out death she shook her head sadly and when she said ‘and we cried and we cried and we cried’ I felt chastened by her pity.

I thought of all the hopes and ambitions that had driven them to this place to meet, however fleetingly, with Anna and touch her with the brilliance of their lives, and then they were gone, and Anna’s life was for ever coloured by the memories of their kindness and humanity.

We live within such a tiny capsule of time yet it seems vast until death rudely makes it so insignificant. It humbles us. I glanced up at the Eiger bathed in warm afternoon sunshine and thought of those terrible storm-torn days sixty-five years ago and a young girl staring up at the face hoping against hope that the young men would return.

‘Did you know Hinterstoisser and Toni Kurz?’ Ray asked and Anna shook herself from sad memories and smiled in recognition.

‘Oh, of course,’ she said. ‘In the early years we met many of the climbers coming for the wall.’

‘You met Toni Kurz?’ I was aghast.

‘Yes, yes, he was a fine boy.’

‘Who was the leader? Was it Hinterstoisser? He was supposed to be the master climber.’

‘Yes, perhaps he was, but it was Rainer who was the leader. He was so strong, like this.’ Anna broadened her shoulders to mimic a body-builder’s physique. ‘A strong man. He was the leader.’

‘And Hinterstoisser?’

‘Yes, he was good but not the leader. We watched them climb,’ Anna said. ‘I saw Angerer hit by the rock-fall. Rainer bandaged his head.’

‘How?’ Ray asked in amazement.

‘We had a big telescope outside the hotel. I was always watching. It is upstairs if you wish to see it. We took it down from Alpiglen when we decided to sell the hotel.’

‘Yes, that would be good to see,’ Ray said.

‘What was Angerer like?’ I asked feeling a little guilty at interrogating Anna so insistently but I couldn’t resist the opportunity to hear about these men at first hand. I knew the story of their lives and deaths so well that I wanted this chance to know them more intimately, to have them brought vividly to life by the fond and melancholy memory of an old lady who had witnessed their passing.

‘Oh, Angerer,’ Anna said with a fond smile. ‘He was so pretty. He was like a girl, so slim, and his face, very smooth just like a girl. And always he was looking at his sweetheart. He had a photograph of her hanging around his neck and always he was looking …’

It was an poignant detail that neither of us had ever considered. After all they were simply names on a page. It had never really occurred to us that they had loved ones. I thought of the three long bitterly cold bivouacs that Angerer had endured after being struck on the head by a rock. When they had reached the Flat Iron it became apparent that his condition was worsening. By the time they had retreated to the Swallow’s Nest and Hinterstoisser was desperately attempting to reverse his Traverse, Angerer was observed to be slumped to one side, no longer taking any part in the proceedings.

‘And Kurz? How was he?’ Ray asked.

‘He was young. They were all so young,’ Anna said. ‘His was a terrible death, very sad.’

I thought of a boyish Kurz sitting in a meadow with alpine flowers at his feet, shelling a boiled egg, staring back at me from that old photograph. It was he who had brought me here. His life and his death, insignificant, I suppose, given the countless tragedies that had ensued in the intervening years, had stayed with me from the moment I had first read about him. Anna’s story had suddenly made him as real as if he had sat by me only days before.

The world has a life of its own. Nothing we do affects it. It goes on and on, never looking back, unaware of a past, oblivious to the future, never hesitating in its inexorable progress through time. If life were not to have death at its end and had death not been preceded by life, neither would have any meaning. We need to die or our lives are meaningless. The poet, Yasar Kemal, seemed to sum it up when he wrote:

Anybody, whether a novelist or not, must have purpose in life. And that purpose is to understand human reality in the face of death. Death only exists because there is life. That is the great poetry of the world. That is its reality.

If Toni Kurz had not died on the Eiger, if Max Sedlmayr and Karl Mehringer had not passed this way then nor would I. They gave meaning to my actions.

‘Did they stay in the hotel?’ Ray asked.

‘Oh no, they were very poor. We let them stay in the wood shed. One franc a night,’ she added chuckling. ‘They cut wood for us, always helping out.’

We spent an hour listening to Anna’s reminiscences, avidly looking through her extraordinary scrapbook of history. When at last she left we sat back and stared at each other in amazement.

‘Well, that’s made the holiday,’ I said. ‘Whatever happens, it won’t beat that.’

‘No,’ Ray agreed and stood up. ‘I’m going to sort out my kit for tomorrow. What time’s the first train?’

‘Seven, I think,’ I said. ‘I’ll set the alarm early and get a good breakfast on for us. We should be on the face by eight-thirty. Anyway, there’s no rush. We’ll have all day to reach the Swallow’s Nest.’

‘Yeah, that’s true.’ Ray turned and walked back to the room. I rang Pat Lewis, my long-suffering partner, to tell her the great news about the forthcoming climb. She seemed a little less enthusiastic than me. She started to tell me to be careful and then stopped. We had been through that scenario too many times. ‘Take care of Ray for me,’ she said. She had a soft spot for Ray and I promised I wouldn’t let him out of my sight.

‘I’ll ring you as soon as we get down. I won’t have the phone on to save the batteries. Don’t worry about us. We’ll be having fun.’

I opened my book and tried to read, but the setting sun was painting the mountains in crimson light and distracting me from the words.

I put my book down and glanced up at the mountain as the sun angled across the ice fields illuminating the Ramp in a wash of gold. We were making an attempt on the face the following morning but the combination of sunshine, a strong gin and a second reading of

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin

had helped drive the prospect clean from my mind. It was a wonderful, hypnotic novel of fabulous scope, swinging between joy and bleakness: lyrical, angry and earnest. I felt calm and relaxed as I watched an isolated cumulus cloud drift in to the great amphitheatre of the face. A breeze scattered it into tendrils of mist that hung around the icy rim of the Spider until the sun burned it from existence.

I read for an hour, struggling with the fading light, completely enthralled by the words, forgetting for the first time in weeks the insistent, mesmeric pull which the Eiger had been exerting on me; I had escaped its shadow. As I returned to the book it occurred to me that the only reason I was here was because of reading; it was the reason I began to climb.

There is something about reading that takes you beyond the constrictions of space and time, frees you from the limitations of social interaction and allows you to escape. Whoever you encounter within the pages of a book, whatever lives you vicariously live with them can affect you deeply – entertain you briefly, change your view of the world, open your eyes to a wholly different concept of living and the value of life. Books can be the immortality that some seek; thoughts and words left for future generations to hear from beyond the grave and awaken a memory of another’s life.

Climbing taught me how to look at the mountains, how to read their secrets and survive on their heights. More recently, particularly since I began to write, it taught me how to look at people – myself included – to see how we behave, how climbing changes us. I feel that the frontier of climbing is no longer technical or geographical but ethical. This is what climbing should be about: using the tradition, ethos and passion of our sport to arouse greater responses within ourselves, echoes of what we would like to be.

After having climbed a great classic route I always thought that I never wanted to repeat it. It was unique, intensely personal, and I never wished to lose that perfect sense of it or the passion which had driven me to climb it.

It had always seemed to me that passion, like love, should never fade. I had read that in love you should not do things by halves, that if you love a woman you should love her entirely, give everything. You don’t make love to other women, you don’t take her for granted. It is something I am painfully aware that I have always failed to do. The mountains had made me selfish and I could love no one entirely because of them, or so I told myself. Then again I had once thought that I loved mountains in this way, unequivocally, selflessly: once this was true to the loss of everything else. With the eroding passage of the years I now sometimes think that even here I failed.

As I sat reading in the sunshine, sipping an iced drink and glancing occasionally at the looming majesty of the Eigerwand rearing out of the meadows in front of my chalet, I realised that I was finding it difficult to leave the mountains. In a way I had come back to my roots, but with the passing of the years and of so many friends I suspected that my passion had been eroded.

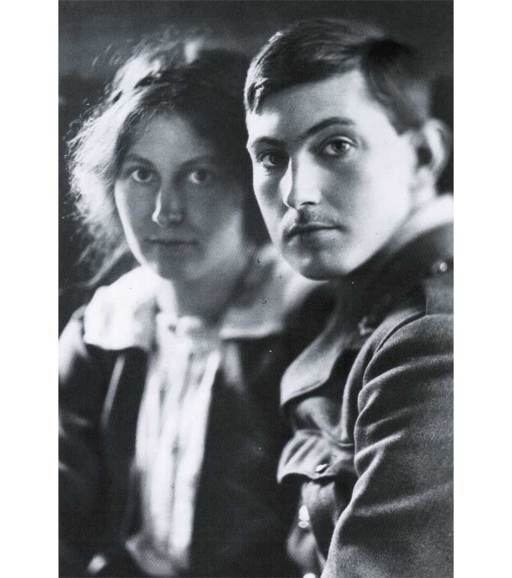

The wildest dream:George and Ruth Mallory.

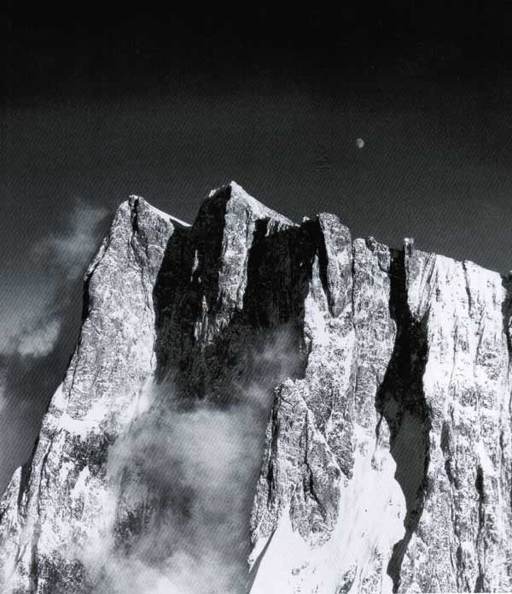

Moon rises over the Walker Spur. Grandes Jorasses, Chamonix. Photo by Bradford Washburn.

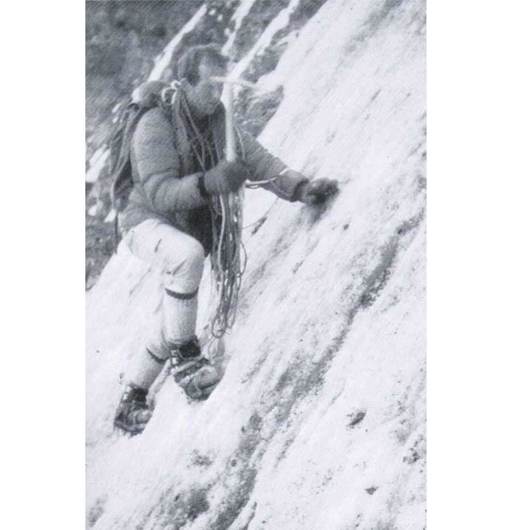

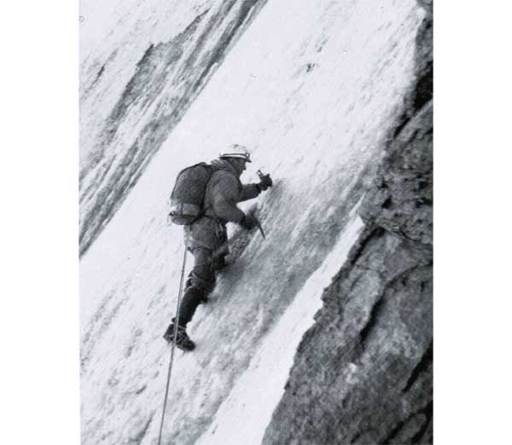

Chris Bonington cutting steps into the Spider on the first British ascent, 1962.

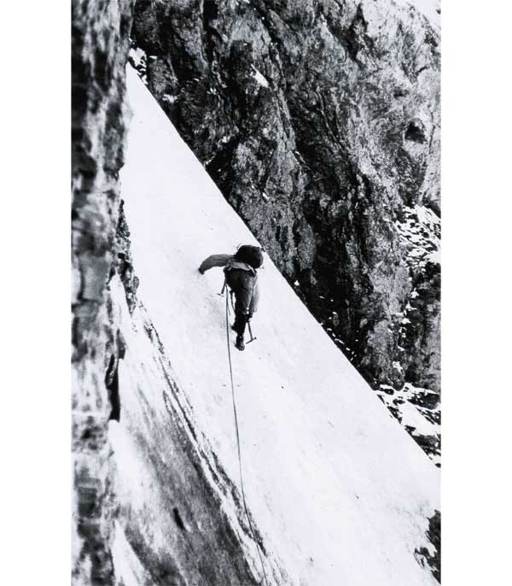

Don Whillans climbing the First Ice Field using an ice dagger.