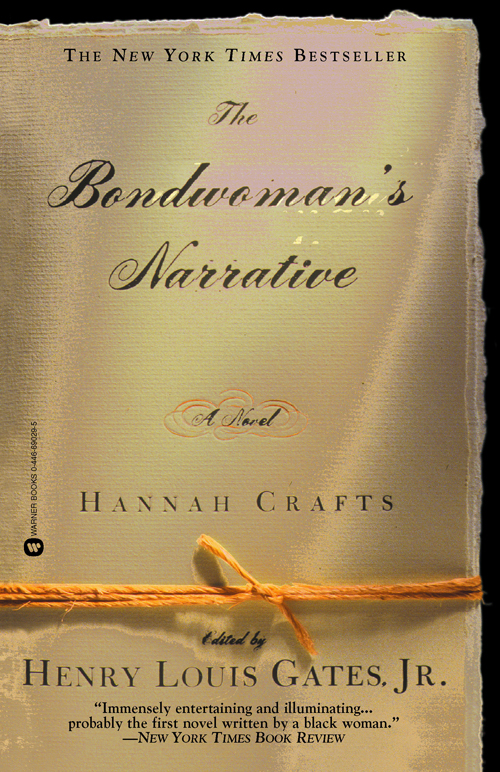

The Bondwoman's Narrative

Copyright © 2002 by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

First eBook edition: April 2002

ISBN: 978-0-7595-2764-5

CONTENTS

C

HAPTER

2: The Bride And T he Bridal Company

C

HAPTER

3: Progress In Discovery

C

HAPTER

13: A Turn of The Wheel

C

HAPTER

15: Lizzy’s Story Continued

A N

OTE ON

C

RAFTS’S

L

ITERARY

I

NFLUENCES

A

LSO BY

H

ENRY

L

OUIS

G

ATES

, J

R

.

The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American

Literary Criticism

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man

The African-American Century: How Black Americans

Have Shaped Our Country

(with Cornel West)

Colored People: A Memoir

(with Cornel West)

Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American

Experience

(with Kwame Anthony Appiah)

E

DITED BY

H

ENRY

L

OUIS

G

ATES

, J

R

.

Our Nig; or, Sketches from the Life of a Free Black by Harriet E. Wilson

In memory

of

Dorothy Porter Wesley,

1905–1995

on whose shoulders

we stand.

The Search for a Female Fugitive Slave

Each year, Swann Galleries conducts an auction of “Printed & Manuscript African-Americana” at its offices at 104 East Twenty-fifth

Street in New York City. I have the pleasure of receiving Swann’s annual mailing of the catalogue that it prepares for the

auction. The catalogue consists of descriptions of starkly prosaic archival documents and artifacts that have managed, somehow,

to surface from the depths of the black past. To many people, the idea of paging through such listings might seem as dry as

dust. But to me, there is a certain poignancy to the fact that these artifacts, created by the disenfranchised, have managed

to survive at all and have found their way, a century or two later, to a place where they can be preserved and made available

to scholars, students, researchers, and passionate readers.

The auction is held, appropriately enough, in February, the month chosen in 1926 by the renowned historian Carter G. Woodson

to commemorate and encourage the preservation of African American history. (Woodson selected February for what was initially

Negro History Week, because that month contained the birth dates of two presidents, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln,

as well as that of Frederick Douglass, the great black abolitionist, author, and orator.)

For our generation of scholars of African American Studies, African American History Month is an intense period of annual

conferences and commemorations, endowed lecture series and pageants, solemn candlelight remembrances of our ancestors’ sacrifices

for the freedom we now enjoy—especially the sacrifices of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—and dinners, concerts,

and performances celebrating our people’s triumphs over slavery and de jure and de facto segregation. We have survived, we

have endured, indeed, we have thrived, Black History Month proclaims, and our job as Carter Woodson’s legatees is, in part,

to remind the country that “the struggle continues” despite how very far we, the descendants of African slaves, have come.

Because of time constraints, I usually participate in the auction by telephone, if at all, despite the fact that I devour

the Swann catalogue, marking each item among its nearly four hundred lots that I would like to acquire for my collection of

Afro-Americana (first editions, manuscripts, documents, posters, photographs, memorabilia) or for the library at my university.

This year’s catalogue was no less full than last year’s, reflecting a growing interest in seeking out this kind of material

from dusty repositories in crowded attics, basements, and closets. I made my way through it leisurely, keeping my precious

copy on the reading stand next to my bed, turning to it each night to fall asleep in wonder at the astonishing myriad array

of artifacts that surface, so very mysteriously, from the discarded depths of the black past. Item number 20, for example,

in this year’s catalogue is a partially printed document “ordering several men to surrender a male slave to the sheriff against

an unpaid debt.” The slave’s name was Aron, he was twenty-eight years of age, and this horrendous event occurred in Lawrence

County, Alabama, on October 30, 1833. Lot 24 is a manuscript document that affirms the freed status of Elias Harding, “the

son of Deborah, a ‘coloured’ woman manumitted by Richard Brook … [attesting] that he is free to the best of [the author’s]

knowledge and belief.” Two female slaves, Rachel and Jane, mother and daughter, were sold for $500 in Amherst County, Virginia,

on the thirteenth of October in 1812 (lot 13). The last will and testament (dated May 9, 1825) of one Daniel Juzan from Mobile,

Alabama, leaves “a legacy for five children he fathered by ‘Justine a free woman of color who, now, lives with me’” (lot 17).

These documents are history-in-waiting, history in suspended animation; a deeply rich and various level of historical detail

lies buried in the pages of catalogues such as this, listing the most obscure documents that some historian will one day,

ideally, breathe awake into a lively, vivid prose narrative. Dozens of potential Ph.D. theses in African American history

are buried in this catalogue.

Among this year’s bounty of shards and fragments of the black past, one item struck me as especially interesting. It was lot

30 and its catalogue description reads as follows:

Unpublished Original Manuscript. Offered by Emily Driscoll in her 1948 catalogue, with her description reading in part, “a

fictionalized biography, written in an effusive style, purporting to be the story, of the early life and escape of one Hannah

Crafts, a mulatto, born in Virginia.” The manuscript consists of 21 chapters, each headed by an epigraph. The narrative is

not only that of the mulatto Hannah, but also of her mistress who turns out to be a light-skinned woman passing for white.

It is uncertain that this work is written by a “negro.” The work is written by someone intimately familiar with the areas

in the South where the narrative takes place. Her escape route is one sometimes used by run-aways.

The author is listed as Hannah Crafts, and the title of the manuscript as “The Bondwoman’s Narrative by Hannah Crafts, a Fugitive

Slave, Recently Escaped from North Carolina.” The manuscript consists of 301 pages bound in cloth. Its provenance was thought

to be New Jersey, “circa 1850s.” Most intriguing of all, the manuscript was being sold from “the library of historian/bibliographer

Dorothy Porter Wesley.”

Three things struck me immediately when I read the catalogue description of lot 30. The first was that this manuscript had

emerged from the monumental private collection of Dorothy Porter Wesley (1905–95), the highly respected librarian and historian

at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University. Porter Wesley was one of the most famous black librarians and

bibliophiles of the twentieth century, second only, perhaps, to Arthur Schomburg, whose collection constituted the basis of

the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library, which is now aptly named after him. Among her numerous honors was an honorary

doctorate degree from Radcliffe; Harvard’s W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for Afro-American Research annually offers a postdoctoral

fellowship endowed in Porter Wesley’s name. Her notes about the manuscript, if she had left any, would be crucial in establishing

the racial identity of the author of this text.

The second fact that struck me was far more subtle: the statement that “it is uncertain that this work is written by a ‘negro’”

suggests that

someone

—either the authenticator for the Swann Galleries, who turns out to have been Wyatt Houston Day, a distinguished dealer in

Afro-Americana, or Dorothy Porter Wesley herself—believed Hannah Crafts to have been black. Moreover, the catalogue reports

that “the work is written by someone intimately familiar with the areas in the South where the narrative takes place.” So

familiar was she, in fact, with the geography of the region that, the description continues, “her escape route is one sometimes

used by run-aways.” This was the third and most telling fact, suggesting that the author had used this route herself. If the

author was black, then this “fictionalized slave narrative”—an autobiographical novel apparently based upon a female fugitive

slave’s life in bondage in North Carolina and her escape to freedom in the North—would be a major discovery, possibly the

first novel written by a black woman and definitely the first novel written by a woman who had been a slave. (Harriet E. Wilson’s

Our Nig,

published in 1859, ignored for a century and a quarter, then rediscovered and authenticated in 1982, is the first novel published

by a black woman. Unlike Hannah Crafts, however, Wilson had been born free in the North.)