The Book of Secrets

Read The Book of Secrets Online

Authors: Fiona Kidman

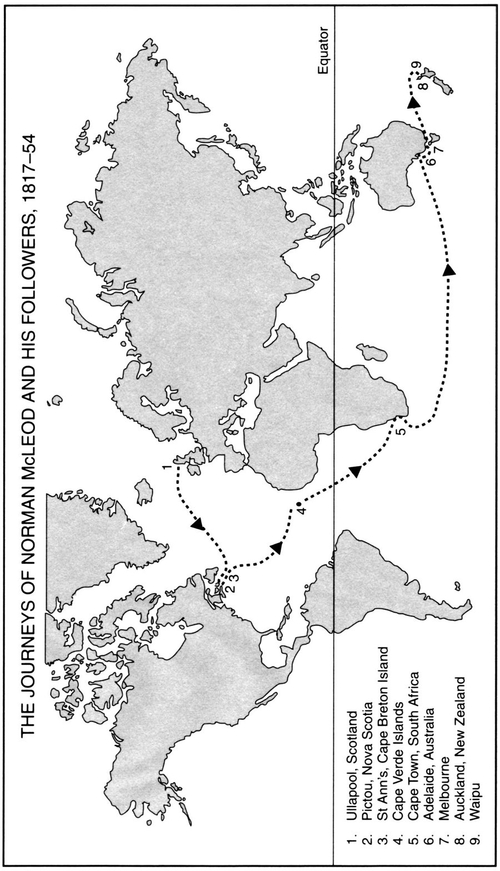

Norman McLeod was a real person, as were many of the people described as having accompanied him on his journeys. They really did undertake the migrations in the circumstances of the book. Beyond this, the work is fiction. All of the people on the Ramsey family tree are fictitious, and so are the family members of Eoghann MacKenzie. Any means of likeness to people, living or dead, in those contexts, are coincidental.

I thank my many informants who spent valuable hours with me; and several more who offered help but whom I was prevented from meeting because of time or distance. For very practical help, I am especially grateful to Warwick Flaus and his wife Janet Cameron, Wellington; John and Sherry MacPherson, Halifax, N.S., and Clinton and Jean MacPherson, Port Morien, N.S.

The people of Waipu set me on the book’s path many years ago, and during their lifetimes the late Misses Lang gave invaluable advice. All of them are remembered with affection and respect.

Thanks are due, too, to Marvin Wodinsky and other staff at the Canadian High Commission in Wellington; to very kind staff at both Public Archives in Halifax, N.S., and at the Beaton Institute, University College of Cape Breton; and also at the Gaelic College, St Ann’s, N.S., and the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington.

In 1985 I held the New Zealand Scholarship in Letters; it was essential to the writing of this book.

M

aria was old and the stairs were steep. There was a wind that evening, not a high one, but a persistent singing across the sea. The old timber creaked, the iron on the roof was almost rusted through; another winter or so and it would be through all over. Already she kept a large china bowl under the leak in the corner of her room.

The state of the roof did not unduly worry her. It would hold for another year or so and that would be long enough. Maria did not intend to live forever. But tonight she was tired, although she didn’t know why, for she had done little except walk to the gate to collect her deliveries after the grocer had left them. They had not spoken to each other, nor had they done so for more than fifty years. It was not the same grocer of course, they had come and gone. The gate was too far away for her to get a good look at them when they stopped, but she always knew when there was a new one. Sooner or later he would have to write a note in response to hers. This was how they did business, she and the men at the store. Each week she wrote a list of the things she needed, and the next week the goods were delivered.

But things had changed as the years passed. They no longer supplied calico, molasses was not always available, there was a shortage of wheat meal, or worse, they did not always know what her orders meant. Once she sent for a stone jar; they sent her back a curious flat bag called a hot water bottle. It took several weeks of notes to establish what this was all about. She nearly went to see the man at the gate but this seemed to be tempting fate.

Doing things this way had worked for so many years that it seemed unwise to alter the pattern. Besides, Maria did not know for sure whether they would allow her to speak with the grocer. Perhaps it no longer mattered what she did, or to whom she spoke, but there were other times when she could not be sure. The edges of the past blurred and fused with the present.

It actually frightened her to think that she might be able to walk through the grass and across the paddock, to open the gate and keep on walking along the dusty path that ran to the village, and into the

shop itself, and that no one would stop her. Maybe they wouldn’t even notice.

When she was halfway up the ladder-like stairs, holding onto the slight rail as she went, one thickened hand after another, there was a smash below, the glass in a window breaking downstairs.

After that, there was a silence for a moment. But then a sound both delicate and biting followed, as if some of the glass had caught on the window ledge, hovered and balanced, then tinkled to the floor.

Voices called.

Ma-ri-a

…

Ma-ri-aa.

Young voices distilled on the night breeze.

Another window smashed.

Maria?

It was a question on the wind now. Would she answer them?

Mari-aa.

Laughter.

Yes, they would notice if she walked down the road. They had not forgotten she was here.

The voices moved away.

Maria was panting with exertion as she reached the top of the stairs. She was not afraid. Fear had flown out the window long before the rocks came through. But if she was honest with herself, there was still anger. It was not just the climb which made her breath rasp.

Three. Three panes now. There were three gaping holes at the front of the house and there was no paper or sacking left to block them up. Why did they do it to her? Would they like to see her ride out of the window onto the old macrocarpa tree on a broomstick? Eh? Was that what they would like? Ah, that she could have flown.

She knew little about flight. But she knew there were aeroplanes. She did not keep in touch with the world and time passed without her always knowing what month, or even year it was, and for the most part she had shunned the newspapers which could have been brought to her house in the delivery van if she chose. But she had avoided seeking them out since the last ones had been used to reline the walls of her bedroom. They were still on her bedroom walls, yellow and brittle with age, the year 1897, the year the world had stopped. Or she had stopped being in the world. It was neither here nor there.

But every now and then one would arrive wrapped around her orders, and then secretly, as if in some perverse rite at which someone might catch her, she would scan each word, reading and re-reading the page and storing it under her bed to look at again some day.

So she had come to know one or two things that went on in the world.

And she had seen the plane overhead, she knew what they were.

Would she have flown if she could? Maria did not know for sure any more, and only vaguely recollected that once, of her own accord, she had made a decision to remain here.

Perhaps fate, and the Man, had decreed that she should be here. Though they were one and the same. Her kinsfolk would say it was God, but she knew better. She thought it was the devil, and to be afraid was pointless for she was committed to darkness and the devil. They were part of a logical process that would never end. There was no heaven.

Something brushed her face, and she almost dropped her candle. Ah — now she was frightened.

But it was a tiny trapped sparrow, more frightened than she was, that had flown in through one of the broken panes.

Ah, her voice soothed — there, there, hush little bird. Don’t be afraid — quiet now, quiet, you’ll beat yourself to death on the rafters. Poor little bird, what were you doing out so late? There now, don’t break yourself.

The sparrow clung to the ceiling beam, tottering as if stunned. She thought it would fall but it recovered itself, staring at her with tiny terrified eyes, its breast rising and falling, the feathers fluffed and trembling.

Well well. Nobody ever asks if they can come in here. Nothing comes for years and sooner or later there’s always something comes crashing through without asking.

— That being the case I suppose there’s no point in telling you to go. No doubt you’ll stay here as long as it’s convenient to you —

She put the candle on the dresser and climbed into bed, then remembered that her hot water bottle was still downstairs. She shivered. It was a long way to go down again. It would be cold by now anyway, lying on the kitchen table, and she had banked the fire up for the night so that it would take a long time to heat more water. She would have to go cold. The blankets were so thin you could see the light through them when they hung on the line for their summer wash. They scratched against her chin.

The bird stirred on the rafter, stretched its wings and cheeped.

In spite of the wind, she slept. She dreamed.