The Book of Secrets (2 page)

Read The Book of Secrets Online

Authors: Fiona Kidman

I

have lived alone in this house for a long time. I have not kept records. I do not have marks on the wall, or diaries, though I am the keeper of certain books which do not belong to me but have fallen into my hands. I have a suspicion that these things never happen entirely by chance, for among them is what I call the book of secrets. This was my grandmother’s way of telling it, the secrets of her life. They are secrets to which I am linked through being her kin, and we are bound by the common thread of my mother’s life. Once I would have dismissed this as being of no importance but now I can no longer ignore it, the binding together which it made. We all had a voice, a way of telling it.

I will come back to the secrets, for they haunt me always, but now it is time for me to tell it, for myself. I tell it aloud as I go, here in this house, though no one can hear me while my hands move across the page.

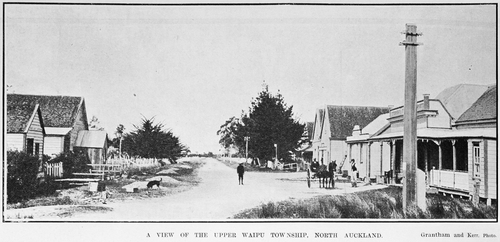

I am Maria McClure. I was born at Waipu, a coastal village in the northern part of New Zealand, in 1878, twelve years after the Man died. The birth took place in this same old house that I live in now, a board house of two storeys, near the river arm that comes in from the sea.

The house stands alone in a paddock. At the back are macrocarpa trees, and alongside of it a single stark, skeletal giant that has been stripped of its leaves by lightning. The great tree just died. It is not entirely safe, so close to the house, but no one would think to remove it. It stands there bleached white now as the years pass and sometimes in high winds I imagine that it will fall over but it never does.

I think it is about fifty-five years that I have been on my own. I live away from the society of people in the world.

I say in the world, though it is difficult to say much about what the world is like, or what it means to the people who have joined it. I doubt if there are many still alive of those whom I knew when I was forced to abandon their company.

There is only one, whom I dream of seeing, and she came later.

Is she alive out there in the world?

I have come a long way by snow and ice to this land of sunlight.

I? Maybe not I, but those I spoke of, the ones who came before.

I spoke of a Man. His name was Norman McLeod, whom the people also called Tormod. He led a group of men and women across the wide world from the Highlands of Scotland to Pictou in Nova Scotia to St Ann’s on Cape Breton Island to Australia to New Zealand. The journeying took thirty-five years, and longer for some. It was like Moses in the wilderness. It was done in the name of God.

He was born near Stoer Point in rugged Assynt, Sutherland County, Scotland, in 1780.

His parents lived by the parted rocks at Clachtoll in a house of stone and turf. His mother gave birth to him at harvest time when the barley was being gathered, by the light of a fire fuelled with bog fir. The slate grey Atlantic bore a rim of silver on its horizon, but close at hand the wild green sea pounded on the headland of streaming rocks. The machair grass tossed in the wind and a violence was on the land.

McLeod grew tall, and his eyes turned also to cool slate. He had black hair when the journeys began and a lean hard mouth in a thin face. My grandmother said it was a cruel mouth. Others, when they spoke of him, said that he was a caring man who did what he believed was right for the people who followed him. But across the breadth of the world they could not decide whether he really knew what was right for them or not. Now he has lain in the cemetery by the sea for close to ninety years and still, I’ll wager, there will be some who cannot agree. There is no doubt in my mind that he was proud, and that his pride led him to harsh ways. He thought that he knew better than all the Church of Scotland, believed that he had discovered a better path for his people to follow (indeed, you would think he had invented it) and that they were like children who would not know what was in their own best interests. I call that pride. I have been accused of the sin of pride myself, and look where it has landed me. I will shortly tell you.

One thing is for sure, that when the people in the community spoke of the Man, there was only one person to whom they were

referring. Around these parts there are many strange names given to men — they are called the ‘Bear’ and ‘Prince’, ‘Captain’, ‘Red’, ‘the Black’, ‘the Strong One’ and other names to identify one from the other, but if anyone said ‘the Man’, then there was only one and it was him. Though he did call himself Norman, like the Apostle Paul of old. He thought of himself as one with Paul.

His people, who were also mine, were driven out of the

north-west

Highlands of Scotland by the terrible clearances of the crofters a hundred and fifty years back. The crofting people had occupied cottages and land owned by the lairds, since time immemorial. The lairds were like fathers to them, they would do pretty much anything that a laird wanted, including defend him and fight for him. They never thought that they would be evicted from their homes, but things changed after Culloden and Bonnie Prince Charlie. The lairds said they had been betrayed; they were hungry devils who wanted some reason to put the people off the land. That is how it has been told to me. They wanted to run sheep on the land, blackfaces they called them, and there was no room for men and women and children alongside of sheep. They wanted also to make money from the kelp industry. This was a cruel affair, for the people who worked it got killed in the freezing waters of the Atlantic. Oh, but it was very profitable though.

I know about these things because my grandmother told me of them, my grandmother Isabella MacQuarrie, the one they did say that I took after, a wild one, yes, they said it was her I might thank for my wild and wicked ways that have put me away inside this old house far from the sight of decent men and women and certainly of children for fifty-five years. Thanks to her, they say, I am called the witch of Waipu. They may think I do not know of this, but I know more than they think. I know things because I hear them come through the ground in the night, I press my ear to the ground and the word travels; the damp smell of the earth is a revelation. Thank God, I say, for one day I will be put in it for good and it is a fine thing to know I will go on hearing things down there. I am not afraid of being locked in that fastness, the earth is a warm blanket full of hum and carry on. And I can hear stories on the breeze at morning, in the crackle of crickets in the midday sun, and in the birdsong at evening. Ah the old woman is truly mad, she hears voices, they do well to shun me. No, I tell you

it is them that are mad and do not know what is all around them, for I have learned many things, here in my board house by the sea, and I have been told things. For I have not always been alone.

I was banished to this house for the sin of fornication. I was a girl of just twenty years when I met Branco the road mender. At that time the north was full of dark men from Dalmatia, which from my random newspapers I now know as part of Yugoslavia. All the good British people (with whom the Scots were for better or worse lumped in) did not like the Dalmatians in their midst. They were great gum gatherers. That is, they dug out of the ground lumps of a clear hard substance called kauri gum, bright gold in colour though it was translucent. It was used for making varnishes and polishes and it was valuable. They called it poor man’s gold, although a man who was prepared to dig in mud and filth, and not give up on it too easily, could get rich with greater certainty than those who sought gold. That was what the Scots and English would do, not take it seriously, just go on digging for a bit when it suited them and not stick with it. But the Dalmatian, well, he would dig and dig, and take his pickings to the trading post and get his money and go back to the fields and go at it again and again, and after a while he’d accumulate enough money to buy a farm and the others would have nothing, like as not drank it away. They got to believing that the Dallies were stealing from them; they certainly felt superior. And some of the Dallies looked round and saw that it was nothing but land hunger and greed, and nobody to service the landscape or do any of the dirty work, so they decided to do that as well, and get richer in the process. Branco was a workman but he planned to get rich, make no mistake about that.

I wonder sometimes if he ever did.

My dark and curly-headed foreigner had come in off the gumfields when I first met him. I saw him that first time one morning when I was shaking the crumbs off the tablecloth outside the house.

Only then I was still a girl, and I lived here with my mother who was a widow. My grandmother was not long dead and we often grieved for her. Well, that is partly true, for I was beside myself with sorrow for the old lady. I cannot tell you, even now, how much I loved the old woman. But I think my mother was weary of her. She needed her, but I do not think she ever liked her much. There were stories

about my grandmother, about her early years. As I have said, there was much blamed on my grandmother for the way that I was when younger. I never saw any sign of impropriety about her, but piecing together here and there things that were told to me and things that I have found out since, here in this house, there was a kind of truth in it all.

She had spirit, she had a way of telling tales that made ordinary things shine, that I do know. She was nearly a hundred when she died, and that was another thing about her, that her life went on and on, which is not necessarily a good thing for the children. You can go at it, this business of living, for too long. That is what has happened to me, I suppose. When they decided that I should stay here in this house, they never imagined it carrying on like this year after year, they believed it would all be over soon — I don’t know how they thought it would be resolved, but you just know about people, they don’t conceive of a situation going on forever and outliving them. In their secret heart of hearts they would see this as outwitting them, and that is what people do not care for.

The night before I met Branco I had seen my grandmother in a dream. She was propped up in bed with her long white hair straggling against the pillows, both so white you could hardly tell one from the other, just the way she had been in the last days of her life. Only in those days her eyes had been half shut, a slit of colour in the seams of skin that covered the place where her eyes should have been, and her voice was a half whisper. She made little sense, only some days she would take my hand and raise it to the window and then I would know that I must open it when there was no one around, and let the wind touch her face. She would lift her face, her once beautiful, fine-boned profile, matted with thick flesh now like a giant pale curd, covered in whiskers, to feel the brush of the air. In the dim light that was kept on in the room I would see only the outline of her face, but the breeze would take away the fetid odours of her dying body, and I would touch her hand, still cool and dry, and remember her as she had been. Her hand would return my pressure and then I would quickly close the window so that we were not discovered. It was the nearest to rebellion, and a communication, that I had experienced with her in a long time, and I would often think that the next day she would speak to me, say something special that she had saved for me and only me, but the days passed and what she had to say never

came, and then she died and I was alone with my widow mother who was strict and harsh in her views of the world and observed the Sabbath with the intensity of the old people.

No one can know, who has not experienced it, how strict and fierce the Sabbath was. Back in Cape Breton, come Saturday nights, the sap trays which caught the maple syrup were overturned so that no syrup could collect on Sunday, no pleasure was observed and if accidental pleasure was taken in performing the Lord’s work, like skating across the ice to church, the Man would take the skates and hurl them in the waters beneath the ice. There was no preparation of food allowed, no exchanging of money no matter how great the need for goods, no admiration of the handiwork of children, no singing, no whistling, no dancing, no playing of musical instruments, nothing at all. There was, though, a great deal of praying and reading of Scriptures and sitting around with a face like a green raspberry, oh yes.

I’m not saying it was quite as bad as that when we came out here but it wasn’t much better. My mother, who took very much to heart her responsibilities to her fatherless child and unluckier even than most with the cross of a witch in the house, made sure it was as much like the old days as possible.

Except that in my grandmother’s time, if she were around she managed to cast me a mocking smile that stopped it from being so bad, and I think my mother must have known. Yes, I think that among other things, she did not like my grandmother for not being as attentive to the Sabbath as she might have been, and this stemmed from somewhere back in time, to the place whence they both had come, and beyond that to my grandmother’s homeland. She was afraid I would be corrupted; directly, you might say, as if the bad blood which ran in my veins was not enough. Not that she was untouched herself, of course, but the way my mother acted you would think she had put a cleansing rinse through her own veins.

I speak harshly of my mother. Yet in truth, she loved me. That remains my dilemma. I did not, could not, hate her. I did not like her much, but surely that is a different matter.

In the end it was a life for a life. That is not easy to accept. But she chose to live her life in the mould of the old people. I did not choose that my life should be the same, however she tried to make it

as hers. She paid with her life, but she left the old people to nest in my dreams.

And it has gone on for so long. So long, I tell you, whoever can hear me, whoever is listening.

This night, the one that I spoke of, when I was young and before it had all come to pass, I had seen my grandmother in my dream and her hair hung and her breath laboured and her flesh stank; her skin was the colour of scone dough but her eyes were wide open. Yes, that is what I am coming to, those wide shining eyes. They were twinkling and shining in the gloom of that deathbed room. They were as big as saucers and dark as the centre of a Black-eyed Susan. I leaned towards her and I knew that she was about to tell me the secret I had been waiting to hear and then I woke.