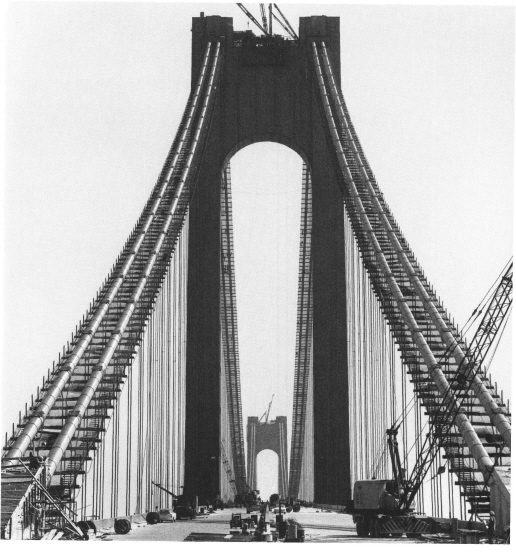

The Bridge (8 page)

Authors: Gay Talese

But he did admit that bridge building, like boxing, was a young man's game.

And of all the eager young men working on the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge under Hard Nose Murphy in the fall of 1963, few seemed

better suited to the work or happier on a bridge job than the two men working together atop the cable 385 feet over the water

behind the Brooklyn tower.

One was very small, the other very large. The small man, standing five feet seven inches and weighing only 138 pounds—but

very sinewy and tough—was named Edward Iannielli. He was called "The Rabbit" by the other men because he jumped the beams

and ran across wires, and everybody said of the twenty-seven-year-old Iannielli that he would never live to be thirty.

The big boy was named Gerard McKee. He was a handsome, wholesome boy, about two hundred pounds and six feet three and one-half

inches. He had been a Coney Island lifeguard, had charm with women and a gentle disposition, and all the men on the bridge

immediately took to him, although he was not as friendly and forward as Iannielli.

On Wednesday morning, October 9, the two climbed the cables as usual, and soon, amid the rattling of the riveters and clang

of mallets, they were hard at work, heads down, tightening cable bolts, barely visible from the ground below.

Before the morning was over, however, the attention of the whole bridge would focus on them.

It was a gray and windy morning. At 6:45 A.M. Gerard McKee and Edward Iannielli left their homes in two different parts of

Brooklyn and headed for the bridge.

Iannielli, driving his car from his home in Flatbush, got there first. He was already on the catwalk, propped up on a cable

with one leg dangling 385 feet above the water, when Gerard McKee walked over to him and waved greetings.

The two young men had much in common. Both were the sons of bridgemen, both were Roman Catholics, both were natives of New

York City, and both were out to prove something—that they were as good as any boomer on the bridge.

They quietly resented the prevailing theory that boomers make the best bridgemen. After all, they reasoned, boomers were created

more out of necessity than desire; the Indian from the reservation, the Southerner from the farm, the Newfoundlander from

the sea, the Midwesterner from the sticks—those who composed most of the boomer population—actually were escaping the poverty

and boredom of their birthplaces when they went chasing from boom town to boom town. Iannielli and McKee, on the other hand,

did not have to chase all over America for the big job; they could wait for the job to come to them, and did, because the

New York area had been enjoying an almost constant building boom for the last ten years.

And yet both were impressed with the sure swagger of the boomer, impressed with the fact that boomers were hired on jobs from

New York to California, from Michigan to Louisiana, purely on their national reputations, not on the strength of strong local

unions.

This realization seemed to impress Iannielli a bit more than McKee. Perhaps it was partly due to Iannielli's being so small

in this big man's business.

He, like Benny Olson, desperately wanted to prove himself, but he would make his mark not by cutting big men to size, or by

boasting or boozing, but rather by displaying cold nerve on high steel—taking chances that only a suicidal circus performer

would take—and by also displaying excessive pride on the ground.

Iannielli loved to say, "I'm an ironworker." (Bridges are now made of steel, but iron was the first metal of big bridges,

and the first bridgemen were called "ironworkers." There is great tradition in the title, and so Iannielli—and all bridgemen

with pride in the past—refer to themselves as ironworkers, never steelworkers.)

When Edward Iannielli first became an apprentice ironworker, he used to rub orange dust, the residue of lead paint, into his

boots before taking the subway home; he was naive enough in those days to think that passengers on the subway would associate

orange dust with the solution that is coated over steel during construction to make it rustproof.

"When I was a little kid growing up," he had once recalled, "my old man, Edward Iannielli, Sr., would bring other ironworkers

home after work, and all they'd talk about was ironwork, ironwork. That's all we ever heard as kids, my brother and me. Sometimes

my old man would take us out to the job, and all the other ironworkers were nice to us because we were Eddie's sons, and the

foreman might come over and ask, 'You Eddie's sons?' and we'd say, 'Yeah,' and he'd say, 'Here, take a quarter.' And that

is how I first started to love this business.

"Later, when I was about thirteen or fourteen, I remember going out to a job with the old man and seeing this big ladder.

And I yelled to my father, 'Can I climb up?' and he said, 'Okay, but don't fall.' So I began to climb up this thing, higher

and higher, a little scared at first, and then finally I'm on the top, standing on this steel beam way up there, and I'm all

alone and looking all around up there, looking out and seeing very far, and it was exciting, and as I stood up there, all

of a sudden, I am thinking to myself, 'This is what I want to do!'"

After his father had introduced him to the business agent of Local 361, the ironworkers' union in Brooklyn, Edward Iannielli,

Jr., started work as an apprentice.

"I'll never forget the first day I walked into that union hall," he had recalled. "I had on a brand-new pair of shoes, and

I saw all those big men lined up, and some of them looked like bums, some looked like gangsters, some just sat around tables

playing cards and cursing.

"I was scared, and so I found a little corner and just sat there, and in my pocket I had these rosaries that I held. Then

a guy walked out and yelled, Ts young Iannielli here?' and I said, 'Here,' and he said, 'Got a job for you.' He told me to

go down and report to a guy named Harry at this new twelve-story criminal court building in downtown Brooklyn, and so I rushed

down there and said to Harry, T'm sent out from the hall,' and he said, 'Oh, so you're the new apprentice boy,' and I said,

'Yeah,' and he said, 'You got your parents' permission?' and I said, 'Yeah,' and he said, 'In writing?' and I said, 'No,'

and so he said, 'Go home and get it.'

"So I get back on the subway and go all the way back, and I remember running down the street, very excited because I had a

job, to get my mother to sign this piece of paper. Then I ran all the way back, after getting out of the subway, up to Harry

and gave him the piece of paper, and then he said, 'Okay, now I gotta see your birth certificate.' So I had to run all the

way back, get another subway, and then come back, and now my feet in my new shoes are hurting.

"Anyway, when I gave Harry the birth certificate, he said, 'Okay, go up that ladder and see the pusher,' and when I got to

the top, a big guy asked, 'Who you?' I tell 'im I'm the new apprentice boy, and he says, 'Okay, get them two buckets over

there and fill 'em up with water and give 'em to the riveting gang.

"These buckets were two big metal milk cans, and I had to carry them down the ladder, one at a time, and bring them up, and

this is what I did for a long time—kept the riveting gangs supplied with drinking water, with coffee and with rivets—no ifs

and buts, either.

"And one time, when I was on a skyscraper in Manhattan, I remember I had to climb down a ladder six floors to get twenty coffees,

a dozen sodas, some cake and everything, and on my way back, holding everything in a cardboard box, I remember slipping on

a beam and losing my balance. I fell two flights. But luckily I fell in a pile of canvas, and the only thing that happened

was I got splashed in all that steaming hot coffee. Some ironworker saw me laying there and he yelled, 'What happened?' and

I said, T fell off and dropped the coffee,' and he said,

'You dropped the coffee!

Well, you better get the hell down there fast, boy, and get some more coffee.'

"So I go running down again, and out of my own money— must have cost me four dollars or more—I bought all the coffee and soda

and cake, and then I climbed back up the ladder, and when I saw the pusher, before he could complain about anything, I told

him I'm sorry I'm late."

After Edward Iannielli had become a full-fledged ironworker, he fell a few more times, mostly because he would run, not walk

across girders, and once—while working on the First National City Bank in Manhattan—he fell backward about three stories and

it looked as if he was going down all the way. But he was quick, light and lucky—he was "The Babbit," and he landed on a beam

and held on.

"I don't know what it is about me," he once tried to explain, "but I think it all has something to do with being young, and

not wanting to be like those older men up there, the ones that keep telling me, 'Don't be reckless, you'll get killed, be

careful.' Sometimes, on windy days, those old-timers get across a girder by crawling on their hands and knees, but I always

liked to run across and show those other men how to do it. That's when they all used to say, 'Kid, you'll never see thirty.'

"Windy days, of course, are the hardest. Like you're walking across an eight-inch beam, balancing yourself in the wind, and

then, all of a sudden, the wind stops—and you temporarily lose your balance. You quickly straighten out—but it's some feeling

when that happens."

Edward Iannielli first came to the Verrazano-Narrows job in 1961, and while working on the Gowanus Expressway that cut through

Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, to the bridge, he got his left hand caught in a crane one day.

One finger was completely crushed, but the other, cleanly severed, remained in his glove. Dr. Coppola was able to sew it back

on. The finger would always be stiff and never as strong as before, of course; yet the surgeon was able to offer Edward Iannielli

two choices as to how the finger might be rejoined to his hand. It could either be set straight, which would make it less

conspicuous and more attractive, or it could be shaped into a grip-form, a hook. While this was a bit ugly, it would mean

that the finger could more easily be used by Iannielli when working with steel. There was no choice, as far as Iannielli was

concerned; the finger was bent permanently into a grip.

When, in the fall of 1963, Gerard McKee met Edward Iannielli and saw the misshapen left hand, he did not ask any questions

or pay any attention. Gerard McKee was a member of an old family of construction workers, and to him malformation was not

uncommon, it was almost a way of life. His father, James McKee, a big, broad-shouldered man with dark hair and soft blue eyes—a

man whom Gerard strongly resembled—had been hit by a collapsing crane a few years before, had had his leg permanently twisted,

had a steel plate inserted in his head, and was disabled for life.

James McKee had been introduced to ironwork by an uncle, the late Jimmy Sullivan, who had once been Hard Nose Murphy's boss

in a gang. The McKee name was well known down at Local 40, the union hall in Manhattan, and it had been quite logical for

James McKee, prior to his accident, to take his three big sons down to the hall and register them in the ironworkers' apprentice

program.

Of the three boys, Gerard McKee was the youngest, tallest and heaviest—but not by much. His brother John, a year older than

Gerard, was 195 pounds and six feet two inches. And his brother Jimmy, two years older than Gerard, was 198 pounds and six

feet three inches.

When the boys were introduced to union officials of Local 40, there were smiles of approval all around, and there was no doubt

that the young McKees, all of them erect and broad-shouldered and seemingly eager, would someday develop into superb ironworkers.

They looked like fine college football prospects—the type that a scout would eagerly offer scholarships to without asking

too many embarrassing questions about grades. Actually, the McKee boys had never even played high school football. Somehow

in their neighborhood along the waterfront of South Brooklyn, an old Irish neighborhood called Red Hook, the sport of football

had never been very popular among young boys.

The big sport in Red Hook was swimming, and the way a young boy could win respect, could best prove his valor, was to jump

off one of the big piers or warehouses along the waterfront, splash into Buttermilk Channel, and then swim more than a mile

against the tide over to the Statue of Liberty.

Usually, upon arrival, the boys would be arrested by the guards. If they weren't caught, they would then swim all the way

back across Buttermilk Channel to the Red Hook side.

None of the neighborhood boys was a better swimmer than Gerard McKee, and none had gotten back and forth through Buttermilk

Channel with more ease and speed than he. All the young bovs of the street respected him, all the young girls who sat on the

stoops of the small frame houses admired him—but none more than a pretty little Italian redhead named Margaret Nucito, who

lived across the street from the McKees.

She had first seen Gerard in the second grade of the parochial school. He had been the class clown—the one the nuns scolded

the most., liked the most.

At fourteen years of age, when the neighborhood boys and girls began to think less about swimming and more about one another,

Margaret and Gerard started to date regularly. And when they were eighteen they began to think about marriage. In the Red

Hook section of Brooklyn, the Catholic girls thought early about marriage. First, they thought about boys, then the From,

then marriage. Though they thought I look was a poor neighborhood of shanties and small two-story frame houses, it was one

where engagement rings were nearly always large and usually expensive. It was marriage before sex m this neighborhood, as

the Church preaches, and plenty of children; and, like most Irish Catholic neighborhoods, the mothers usually had more to

say than the fathers. The mother was the major moral strength in the Irish church, where the Blessed Virgin was an omnipresent

figure; it was the mother who, after marriage, stayed home and reared the children, and controlled the family purse strings,

and eluded the husband for drinking, and pushed the sons when they were lazy, and protected the purity of her daughters.

And so it was not unusual for Margaret, after they tentatively planned marriage and after Gerard had begun work on the bridge,

to be in charge of the savings account formed by weekly deductions from his ironworker's earnings. He would only fritter the

money away if he were in control of it, she had told him, and he did not disagree. By the summer of 1965 their account had

reached $800. He wanted to put this money toward the purchase of the beautiful pear-shaped diamond engagement ring they had

seen one day while walking past Kastle's jewelry window on Fulton Street. It was a one-and-one-half carat ring priced at $1,000.

Margaret had insisted that the ring was too expensive, but Gerard had said, since she had liked it so much, that she would

have it. They planned to announce their engagement in December.

On Wednesday morning, October 9, Gerard McKee hated to get out of bed. It was a gloomy day and he was tired, and downstairs

his brothers were yelling up to him, "Hey, if you don't get down here in two minutes, we're leaving without you." He stumbled

down the steps. Everyone had finished breakfast and his mother had already packed three ham-and-cheese sandwiches for his

lunch. His father, limping around the room, was quietly cross at his tardiness.