The City on the Edge of Forever (9 page)

Read The City on the Edge of Forever Online

Authors: Harlan Ellison

If you add another 6 to that 6000, you get $66,000. $191,000 + 66,000 = $257,000…which is what Roddenberry says the show finally cost. So I didn’t go over budget a stammeringly piddly

six

grand, but rather

sixty-six

grand. (And Solow & Justman’s INSIDE STAT TREK roughly confirms that budget.) But the investigative journalist Joel Angel, whose book about Roddenberry I’ve cited previously, sent me a fax after reading the limited edition of this book, and he made reference to

his

investigations of archives dealing with

Star Trek

, and he advised me as follows:

“Though Roddenberry says in his letter to you of 6/20/67 that ‘City’ came in at $257,000, there is no documentation in the archives to substantiate it. In the first year, according to the documents that

do

exist, no episode cost much more than $192,000. As you will see in Herb Solow’s memo that follows, the approved budget was $185,000.

“The only budget document I could find for the second year was Coon’s ‘Devil in the Dark,’ which ran a month before ‘City.’ Its projected cost, according to the documents, was $187,057; it came in at $192,863.

“Some examples of third year budgets: ‘All Our Yesterdays,’ projected cost: $182,282; final cost: $183,532. ‘The Lights of Zetar,’ projected cost: $168,000; final cost: $ 173,369. ‘That Which Survives,’ projected cost: $175,000 and that’s exactly what it came in at.

“You may also like to know that in the third year, when budgets were cut, Roddenberry approved a raise for himself on at least one script, from the standard $4500 everyone else was getting, to $5500.”

I think it’s reasonable to assume that “City” ran $66,000 over budget…not $6000 as I trumpeted in the limited edition. But you wanna know something? Who gives a shit?! I was a freelance writer, like hundreds of others who worked

Star Trek

and every other television series, and it wasn’t our job to board and budget the show! That was a job for Solow and Justman and Bernie Widin and the other staff members whose job it was to oversee such things. It was the responsibility of these “experts” to advise freelancers what the budget was, and ways in which it could be met if we went over the line. And, in truth, shows go over budget all the time, even scripts written by staff writers. It was, and is, a commonplace problem in the Industry, and not one that difficult to overcome case by case. If they wanted to.

And here’s the capper to Roddenberry’s bleats about the show going $66,000 over budget: it was the

aired version

, which The Great Bird of the Galaxy kept insisting was

his

, THAT WENT 66,000 FUCKING DOLLARS OVER BUDGET! Not my poor, miserable, inept, self-indulgent, extravagant first draft! If

he

couldn’t come up with a script for “City” that came in on budget—after putting all those other “better writers” like Carabatsos, Coon, Fontana and himself to the chore—then how could poor, miserable, inept, etcetera etcetera Ellison be expected to do it!

I mentioned all this to Alan Brennert, the award-winning writer I’ve cited many times in this book (and to whom this volume is dedicated), and he told me:

“As a sometime-producer myself, I can assure you: no matter

who

wrote ‘City,’ it would have cost more than an average episode of

Star Trek

, simply because of the period setting, New York City in the Great Depression. Sure, there was an old New York street on the Paramount lot, but you have to dress that street with vintage cars; you need to rent period clothes for your principals, your extras; to say nothing of the fact that you were making use of only

one

of the show’s usual standing sets (the

Enterprise

bridge), and all the rest—the planet’s surface, Edith’s soup kitchen, the tenement basement, in fact

all

the Old Earth interiors—had to be constructed. Roddenberry

had

to’ve known this from the very first treatment, as did the people responsible for budgeting the segment, it didn’t take them by surprise, and both they and NBC gave you the green light to go to teleplay first draft based on the treatment that contained everything I’ve mentioned. Hell, Roddenberry even boasted in his letter to you that he insisted on quality casting, sets, fx, and the like. Why would he commit to such inevitable budget overages if your script wasn’t as good as it was? I find it the rankest sort of cowardice that he then, for the next thirty years, makes this big deal about

you

not being able to write the story to budget when even

he

couldn’t! Or wouldn’t.”

In his letter to me dated 20 June 1967, less than two months after the segment aired, Roddenberry wrote me:

Dear Harlan: Despite the cuts in sets and cash the final budget figures on “City” were close to $257,000, or about $6,000 over our show budget of $191,000. We might have made it for around $20,000 less if I had not insisted on quality in casting, set constructions, special effects, and so on.

I’ll tell you why I brought Alan Brennert into it at this point. In 1967—even allowing for what may or may not have been a typo—Roddenberry was saying I was $66,000 over budget. (In fact, what he was saying is that he was that much over budget because, don’t forget, by that time they had “saved” my expensive script, they had “modified” my extravagance, so all they were left to shoot was their

own

over-budget version.)

By 1987, in an interview in

Video Review

(March 1987, page 46) that I cited earlier, but which bears refreshing in your mind, here’s what the great model of perfectibility of humanity was saying:

VR

: I remember a time travel episode with Joan Collins.

RODDENBERRY

: I sent Joan a note the other day. I said, “What has happened to our Salvation Army virgin?”

VR

: That was a great episode.

RODDENBERRY

: It was a fun episode to do.

VR

: Who wrote that one?

RODDENBERRY

: Well, it was a strange thing. Harlan Ellison wrote the first draft of it, but then he wouldn’t change it.

VR

: That’s Harlan Ellison.

RODDENBERRY

: Yeah. He had Scotty dealing drugs and it would have cost $200,000 more than I had to spend for an episode.

And by 1990, he was telling the world I had been more than $350,000 over budget!

From $66,000 to $200,000 in just twenty years.

And by 1990, he was telling the world I had been more than $350,000 over budget! Yeah, and I also had Scotty dealing drugs.

A few loose ends, interesting digressions, a moment to catch our breath and depressurize so we don’t get “the bends” from all this intense self-justification and naked animosity. Not to mention speaking considerable ill of the dead. (But then, I have also spoken some ill of the living. I’m an Equal Opportunity Opprobriumist.)

Not

everybody

ate from the poisoned mushroom of Roddenberry flack. The

New York Times Book Review

of 23 December 1993 carried a short review of Shatner’s MEMORIES. And in that little notice, the reviewer, Rosemary L. Bray (whose name I never encountered prior to seeing it on that

Times

page, but whose name raises hosannahs from me every time I now hear it), wrote this:

“…bits of gossip and a record of happy accidents that led to some of the show’s signature moments. For example, the episode snidely considered the best of any

Star Trek

season, ‘The City on the Edge of Forever,’ starring Joan Collins, was a watered-down version of a script by the science fiction writer Harlan Ellison, who so hated the entire experience and its result that he refused to associate with any of the staff again.”

Well, almost right. I still associate with D.C. Fontana and occasionally talk to Johnny Black and even invited Herb Solow and Bobby Justman over to the house when they wanted information for their INSIDE STAR TREK. Leonard Nimoy and George Takei and De Kelley remain friends. We don’t see each other much these days, though Leonard and I, and our wives, went out and had some excellent Indian cuisine about three months before my heart attack, and that’s fairly recently. Walter Koenig and I see and talk to each other all the time.

But I don’t talk to Roddenberry no more.

I’ve mentioned David Alexander elsewhere in this essay. He’s a guy who was hired by Majel Roddenberry to write the “authorized”—that is, sanitized, prettified, heroificated—biography of Gene. It’s been brought to my attention that I seem to manifest some rancor at Mr. Alexander. If I do, it is because I think Mr. Alexander plays with the facts and has done a hired-gun job that maintains myths and untruths that no self-respecting biographer should have allowed to stand. What I guess I’m saying, is that I don’t think there is anything even remotely like evenhandedness in Mr. Alexander’s snow-job about the Great Bird.

I won’t even go into my feelings about Mr. Alexander actually trying, in a court of law, to be named “official biographer” so no one else—including Joel Engel, who wrote that

other

, warts-and-all Roddenberry biobook—would be able to contradict the Martinized version Majel had hired Alexander to write. (March 17, 1994; Case #SP 000 741; Superior Court of the State of California, in and for the County of Los Angeles.)

But what I

would

like to dwell on for a moment, because it is so goddam ludicrous and bogus that I can’t even get pissed at it, all I can do is shake my head in dumbfounded disbelief at the bodacious

chutzpah

of Roddenberry and those who spent their time sucking up to him, is a little number Mr. Alexander and El Supremo ran in an interview in

The Humanist

(March/April 1991; Volume 51, Number 2).

Now remember, folks, before we tumble down

this

weird little rabbit hole into Roddenberryland, that nothing of the story or characters in “City” existed before I wildly dreamed up the plot and presented it to

Star Trek

. It was all outta my head, y’ know what I’m saying here?

But in

The Humanist Interview

titled “Gene Roddenberry: Writer, Producer, Philosopher, Humanist” by David Alexander, we find the eye-opening exchange reproduced here.

To read the interview, visit http://www.ereads.com/cityontheedge

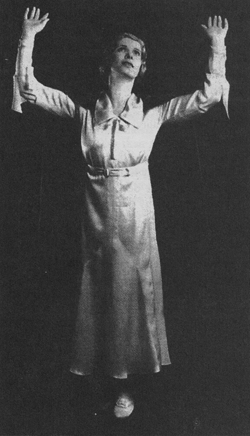

Alexander suggests to Roddenberry that Sister Edith Keeler, a character I created, and whom I based on the famous Aimee Semple McPherson, an historically-prominent evangelist of the 1920s and ’30s, was actually Roddenberry’s brainstorm, based on his father, whom he speaks of admiringly. (I won’t reprise what other books about Roddenberry have said in relation to the Great Bird and his father, and how Bird felt about the old man, and what their relationship was. I am sworn not to get into Roddenberry’s personal life here, for which pledge I am infinitely grateful.)

Above: Flamboyant Pentecostal preacher "Sister" Aimee Semple McPherson (1890-1944) was the first evangelist to recognize the potential of radio to reach a vast "congregation" (Library of Congress)

Now, doesn’t that absolutely fry the fish, folks! Don’t it just warm that illegitimate corner of all our hearts in which lies the most corrosive, mendacious beast of self-aggrandizement we can imagine?

Not only was the miserable, lying sonofabitch shameless in trying to grab credit for having

written

the script, he was not above tacitly acquiescing to the suggestion that it was all his own invention, right from the git-go.

Was I infuriated when one of my readers sent me

that

steaming Alexandrian turd? No, of course not. I am a sensible, rational person, ready to accept the fallaciousness of the existence of Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, and the ability of my poor, stunted brain to create a character so fully-formed and coherent that even now when she goes out on the book-signing circuit, Joan Collins is asked repeatedly about Sister Edith Keeler.

Which brings me to a beauty.

And I don’t mean Collins.

If you’ve read the script, you will remember that Edith Keeler is an humanitarian whose philosophy is one of kindness and compassion. It is stated in the script that she develops, over the next few years, a coherent identifiable philosophy that many people in that post-World War I, semi-Isolationist society found appealing. It is set forth in the teleplay that her philosophy catches on—something like Scientology without the phony scams—and it is sufficiently appealing that it produces a tone in the body politic that briefly keeps America out of the war against Hitler. A brief period that permits the development of the first atomic bomb not by America, but by The Third Reich, and that leads to Germany winning World War II.