The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (69 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

16. T

HE

G

AUNTLET,

N

OVEMBER

30, 1950

The one thing he had decided was that he was going to walk out and fight another day, or he was going to die on that road trying. He was not going to be captured again by anyone. He had gone about four miles down the road on foot when he happened to look up and see a Chinese gunner pointing a machine gun right at him. It was a rare thing, Jones thought, to catch a glimpse of a man who intended to kill you. There was no doubt that he was Chinese, and that he was manning an American 30-caliber machine gun. He was about a hundred yards away, midway on the forward slope of a hill. Jones could see the muzzle flashes even as he dove for a ditch at the side of the road. As he did, he was hit in the foot. Under other circumstances, it might not have seemed like such a terrible wound, but the bullet tore that foot apart and there was a lot of bleeding, and when he tried to put a tourniquet on it, he kept losing consciousness.

Now effectively he had only one foot. He was sure he was going to die. Just then a jeep drove by with Captain Lucian Truscott III, Captain John Carley, and a third officer inside. They saw Jones struggling with his wound—he looked purple, Carley remembered—and they stopped. Truscott carried Jones to the jeep, and the third officer bandaged his foot. Somehow they made it to Sunchon, though Jones had little memory of the rest of the ride. He never learned the name of the officer who had bandaged his foot. He was soon flown to a hospital in Japan. More than fifty years later, Jones was living in a special Army retirement home near Fort Belvoir, when one day he noticed a newcomer and asked if he wanted to join him for lunch. They were both, it turned out, Korean veterans, both former members of the Second Division. In fact both had been caught in The Gauntlet. At a certain point Bill (Hawk) Wood looked at Jones and asked, “Say, you wouldn’t be the officer whose foot I bandaged that day on the road to Sunchon, would you?”

M

ALCOLM MACDONALD, THE

young intelligence officer who had been caught in heavy fire when the Chinese raked Division headquarters on the night of the twenty-ninth, started November 30 by checking the headquarters area. There he found the body of a young friend of his, Lieutenant William Fitzpatrick; he had taken a bullet in the head the previous night. MacDonald had seen a good deal of death in those few days, but the death of someone he knew and liked seemed to mark the day from the start. Later that morning, he was standing outside headquarters with a young photo-interpreter, Private John McKitch, when the Chinese snipers began shooting again. McKitch was hit in the upper arm. Just a little less wind and he gets it in the head, MacDonald thought, and a little more wind and I get it in the gut. The fact that the snipers were zeroing in on them was a sure sign that it was time to go. Then the order to get out came down. Each man could bring his weapon, his ammo, a first aid kit, and a canteen of water. They had to leave their duffels and their arctic sleeping bags—the very few who had them—behind. MacDonald went out in the jeep of Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Foster, the division G-2, and it was start-and-stop all the way, under constant fire.

It was a day of tears, MacDonald thought years later. Some men wept and others perhaps should have. At one point, as they were coming up on The Pass, the convoy stopped and MacDonald walked toward the head of the column to find out what the delay was. Along the way, he saw Butch Barberis, commander of the Second Battalion of the Ninth Regiment, standing by the side of the road. Bullets were landing everywhere, but Barberis seemed immune to danger, in no way afraid of the Chinese, but not moving either. He and MacDonald had been friends, young officers of roughly the same age posted together back at Fort Lewis before the war, and MacDonald had always thought of Barberis as perhaps the single most fearless officer he knew. It was just like Barberis to stand there contemptuous of enemy fire, rallying his troops, MacDonald thought. Then he noticed that Barberis was weeping. “Mac,” his friend said, “I’ve lost my whole battalion.”

On that retreat, just when you thought you had been through the worst of it, there was something worse ahead, something to haunt you for the rest of your life. As they came to The Pass, the convoy began to pick up speed, and MacDonald, by now leading one subsection of it, drove as quickly as he could, because there was safety in speed, and death at every stop. As he came around a big curve, making what was on that road fairly good time, MacDonald saw a two-and-a-half-ton truck lying on its side, and alongside it a bunch of GIs trying to flag him down, pleading with him or anyone else in the convoy to stop. It was as if the entire scene were taking place in slow motion. He did not have to hear them to know what they were saying, that they believed they were going to die unless he helped them.

It was, thought MacDonald, the worst moment of the worst day of his life. If he stopped, he feared, the Chinese would hammer the convoy and then block the road again. He had his mission—to get a jeep already loaded with wounded out and make room for those other vehicles. So he hardened himself and just kept driving. “I said a prayer for those poor souls there along the road and I asked for their forgiveness,” he remembered years later. When he finally reached a small ford at the end of The Pass, one that the Chinese were covering with a devastatingly accurate machine gun, he was sure that he was not going to be able to cross. But then a B-26 came in on a napalm run and took out the machine gun. Finally across, MacDonald had a hard time grasping that he was actually going to live. Of one thing he was sure—none of the men who had been there that day was ever going to be quite the same again.

DUTCH KEISER LEFT

his headquarters in the early afternoon. By the time he went out, he was well aware that his division was caught in a trap of monstrous proportions. He and the other senior officers had given up their vans to the wounded. He was not in good shape. He had been fighting a cold for several days and left wrapped in a parka. The journey out did not favor generals much more than it did enlisted men. At one point Maury Holden, the G-3, was kneeling behind a jeep firing into the nearest Chinese position next to Major Bill Harrington, the assistant G-2. Suddenly Harrington fell over on top of him, shot right through the heart.

Even with the constant fire, Keiser and his group moved reasonably well until they neared The Pass. Then the convoy stalled. So Keiser and the others got out of their jeeps, witnessing the same physical and emotional destruction that so many others had seen. For the first time he realized how completely it had already unraveled—the sheer scope of the tragedy. He was shocked by how few of his men were firing back. He moved among them, shouting, “Who’s in command here?…Can’t any of you do anything?” He finally decided to recon The

Pass himself and began to walk it, at one point trying to step over a body in his path. Tired, he did not get his foot high enough and stepped on the body by mistake. Suddenly, the body spoke: “You damned son of a bitch!” The voice stunned Keiser and he found himself apologizing—“My friend, I’m sorry”—before continuing on his way. It was an epitaph for the day. There was death all around him, and he understood that it did not matter how little help he had gotten from Corps. It was all his responsibility. It was the destruction of

his

division and it was intensely personal. Corporal Jake Thorpe, Keiser’s bodyguard, who had dedicated his life to protecting him, had been killed that afternoon while manning their jeep’s machine gun. At first, they had placed Thorpe’s body in the back of the jeep, but eventually, because there were so many wounded lying along the road, they had had to leave it by the roadside in order to make room. That was a hard thing to do, leaving behind the body of a man who had given his life protecting you.

WHEN GENE TAKAHASHI

finally made it through The Gauntlet, he was stunned by what had happened to his company, his battalion, and his regiment. He had known it was bad, but it had been so much worse than he had realized. Love Company was down to about a dozen men. As far as he could tell, he was the only officer left—all the others had either been killed, seriously wounded, or were missing in action. When they had an assembly a few days later near Seoul, only 10 men of the original 170 of Love Company were there. Of the 600 men in Takahashi’s battalion, only 125 to 150 made it through. As combat units, Love and King companies, which had been on point for the division when the Chinese assault began, no longer existed. The Third Battalion barely existed. And the Ninth Regiment was well under half strength.

AS OTHER UNITS

from the Second Division were being torn up on the Sunchon road, Paul Freeman was trying to save his regiment. In the days after the initial Chinese attack, some of his frustration showed over the fact that he had sensed accurately what was coming and his superiors had ignored him. He told Reginald Thompson of the London

Daily Telegraph

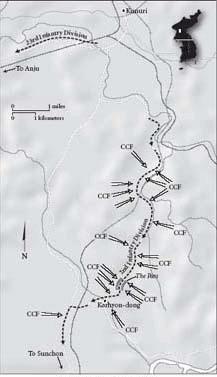

how well the Chinese had been fighting despite their limited hardware. “Without air and artillery they’re making us look a little silly in this godawful country.” On the morning of the thirtieth, his Twenty-third Regiment was the last barrier between the rest of the Second Division and the massive Chinese forces closing in from the north. Its job was to hold the Kunuri perimeter for as long as possible and then follow the Ninth and the Thirty-eighth down the Sunchon road. But Freeman could see that going south was hopeless.

Freeman had been spending a lot of time with his own artillery officers,

Paul O’Dowd, the forward observer for the Fifteenth Field Artillery Battalion, noticed. He was always checking in, asking what they were hearing, and there was a good reason for that, because when all the other forms of communications were breaking down, the artillery generally had the best communications left. The artillery

had

to have good communications; if they didn’t, they risked killing their own troops. So they had their own spotter planes, and their reports from the field were very good, or at least very good on the scale of communications that existed by then. They knew from the start that the road south was only for the dead and dying. O’Dowd, who had been studying Freeman, knew immediately what he was up to, and decided that he was a damn smart officer. Other division officers tended to categorize the artillery as a unit to which you gave orders, not one you listened to. Because of what he was hearing, Freeman decided relatively early in the day to go out on the Anju road, the route Shrimp Milburn had offered to Keiser.

By noon on the thirtieth, Freeman’s position was already desperate. He knew he had very little time left. He could actually see the masses of Chinese troops who had crossed the Chongchon, and he told Division of his growing vulnerability. What made his circumstances even more difficult was how poor his communications with Division were with Keiser on the move. Soon, he could reach Division only through Chin Sloane’s jeep radio, with Sloane, commander of the sister Ninth Regiment, designated to relay messages as best he could to Keiser. Then he lost even that connection. In the early afternoon, Freeman was still trying for permission to go out west. He finally reached Colonel Gerry Epley, the division chief of staff, and Epley told him he could not change his orders. Then the communications got even worse.

Sometime later Freeman reached Sloane and asked if Sladen Bradley, the assistant division commander, could call him—he desperately needed permission to switch his orders. About two-thirty, Bradley called and Freeman made his case to go out west. The decision had to be made immediately—and they had to move before night fell: the Chinese were being held off only by superior American firepower, principally the artillery. With darkness, the enemy would be able to move at will, and Freeman’s regiment would be doomed. He wanted to leave by the Anju road about two hours before dark. About 4

P.M.

Bradley, who had been unable to reach Keiser, called back and gave him permission to do whatever was best for his regiment. Freeman then asked the commanders of units still remaining in the Kunuri area if they wanted to go out with him. Some chose to, some did not.

It was getting toward dusk, and everyone knew how bad the whole thing was. Paul O’Dowd was with the artillerymen who by then were buttoning up their guns, preparatory for the last move. If they went south, it was going to be

a very bad trip, they all knew, because they had two spotter planes flying over the road and the reports on the destruction were shocking. It sounded like a massacre to O’Dowd. But for the moment he had only one job, getting those guns out of there. Lieutenant Colonel John Keith of the Fifteenth Field Artillery Battalion had told him to load up their guns, and he was doing just that, sure that they had fired their last round in the Kunuri region. Just then one of his forward observers, First Lieutenant Patrick McMullan, showed up and started screaming, “Fire mission! Fucking Chinese! Fire mission! Fucking Chinese everywhere! Fire mission!” O’Dowd had never seen McMullan so out of control—he thought maybe he was drunk, for some of the men in other units had been drinking that day. “Fire mission! More fucking Chinese!”

“We’re on closed station march orders,” O’Dowd told him, which was the exact phrase they used for the moment when they had closed it up and were ready to get out. But gradually O’Dowd got more information: the Chinese were moving in for the kill right out in the open in daylight, seemingly thousands of them. Just then Colonel Freeman walked by and asked O’Dowd what was going on, and O’Dowd explained what McMullan had seen. “Get the goddamn guns into fire positions,” Freeman ordered.

There they were, all those Chinese, perhaps five thousand yards away, a vast field of them closing in just as McMullan had said. Freeman told the men that their mission was to delay the Chinese, even if they did not get out in time themselves, even if they did not get out at all. The regiment, Freeman later remembered, unloaded all its weapons and ammo, and the men laid everything out in front of them. This is where they were going to make their last stand, he thought, and quite possibly die. The artillerymen had unloaded the big 105s from the trucks and pointed them in one direction—eighteen howitzers in all, the last guns of Kunuri. It was called a Russian front in the artillery. Paul O’Dowd had fought in two wars, survived the worst of the Naktong fighting, and he had never seen anything like this. Everyone in the unit—cooks, clerk typists—helped take shells off the trucks and carry them to the guns. They fired everything they had in what seemed to O’Dowd about twenty minutes, though it probably took longer. There was a lot of ammo because they had shells that two other artillery units had left behind. They were firing so fast that the guns were overheating and the paint was peeling, just rolling off the guns in giant chunks. The recoil systems on those guns were going to be ruined, O’Dowd decided, but there was no time to worry about that. He was just a little scared that the chambers were so hot the guns might blow.

It was an apocalyptic moment. The noise was deafening, eighteen guns that never stopped. How many rounds went out in that brief span—three, four, five thousand? Who knew? And then, suddenly, it was over. They had fired their

last shell. After all that noise, the silence was overwhelming. Then they destroyed the guns with thermite charges, so the Chinese could not use them. They had completely stopped the Chinese attack, and Freeman believed that, even more important, the Chinese had dug into defensive positions, because an artillery barrage like that often signaled the coming of an infantry attack. The last orders Freeman gave were “Get the hell out of here, and don’t stop!” The road to Anju was completely open and the Twenty-third ran into very little Chinese resistance.