The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (71 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

LATE IN THE

afternoon, Paul Freeman started moving his regiment west toward Anju. After it was all over, there was some muted criticism of him, because he had come out a different route and had not protected the rear of the convoy. But most of the men who knew what happened that day thought he had done the right thing—that whatever terrible fate befell the other units in the convoy, Freeman’s regiment would not have made any difference, because the assault had not come from the rear, it had come from the retreat itself, from the Chinese already in position firing as the division came into their sights. Freeman, most observers thought, had not only done the right thing but had done an exceptional job in responding to changing battlefield pressures and saving what would have been an otherwise doomed unit.

Night was falling as the Twenty-third went west out of Kunuri. They had no idea at what moment the Chinese might strike and cut the Anju road—only that if it happened, they would be bound to the road and badly outnumbered. By chance, the key bridge on the approach to Anju was still in American hands. A company from the Fifth Regimental Combat Team, a part of First Corps, had been sent there to cover its own corps’ retreat. The company commander was a young captain named Hank Emerson, who went on to considerable fame as one of the most audacious commanders during the Vietnam War, when his nickname became The Gunfighter.

At that moment, Emerson’s orders—absolutely terrifying, since the Chinese in great numbers were on the move south—were to try to hold that

bridge until the late afternoon. He had one company with which to do it. Chinese divisions were headed right at him, and the cold was a brutal enemy all its own. (He still remembered quite precisely more than half a century later that the temperature that day hit twenty-three below.) As Emerson waited, he began to think about something that he would ponder for much of his career: what was it like for a unit of infantrymen who believed that those above them had decided they were more or less expendable as part of a larger need for the rest of a division’s survival? Were they some kind of unfortunate offering to the gods of battle? As darkness settled in and the cold only deepened, Emerson’s tension grew. Just when he thought he might be able to leave, a small American spotter plane was shot down nearby, an unwanted sign of just how close the Chinese were.

Emerson and his men had been assigned to rescue the downed flyers, when he happened to look up. There, coming from the east, was an immense caravan of American troops heading toward his bridge. There had been no heads-up from his superiors about an American unit coming through. As far as he could tell, communications being what they were, no one from First Corps knew this unit was coming out. It was like a vast lost patrol appearing out of nowhere, the men looking exhausted and bedraggled, but somehow proud and determined as well. Some men, those who could, were walking, others were crowded into trucks and on top of tanks, sometimes on top of one another. The column stretched as far as he could see. Someone passing by told Emerson they were from the Twenty-third Infantry Regiment.

What Emerson remembered best about that day—other than the fact that when he radioed in, he was then ordered by his superiors to give the Twenty-third all his trucks, which meant that his own men eventually came back riding on the outside of his tanks—was that the commander of the Twenty-third came in on the last vehicle, a jeep with a mounted machine gun. Emerson immediately understood the meaning of that—a commander who had made himself one of the most vulnerable members of his outfit should the Chinese catch up with them. The last man out, Emerson thought, that’s good; that’s what a real commander does. The commander, whose name was Paul Freeman, stopped briefly to talk to him, and was very cool, and very much in command—as if something like this, taking a regiment down a back road to escape three or four Chinese divisions, was something he did every day.

“Son, what outfit is this holding this bridge?” he asked.

He has no more idea who we are than I do who he is, Emerson thought. “Sir, this is Company A of the Fifth Regimental Combat Team.”

“Well, son, God bless Company A of the Fifth Regimental Combat team. Thank you for what you’re doing here.” And then Paul Freeman passed

through, and not long after, Company A pulled out as well. The last units whacked by the Chinese from the west side of the peninsula were now headed south for safer positions and with luck—if that was the word—preparing to fight another day.

It had been one of the worst days in the history of the American Army, surely the worst in the history of the Second Infantry Division, at the end of the worst week in the division’s history. The numbers were heartbreaking. In those finals days of November, the Ninth Regiment had lost an estimated 1,474 men (including non-battle casualties, which usually meant frostbite); the Thirty-eighth Regiment, 1,178; and the Twenty-third, 545. The Second Engineers had lost some 561 men to battle casualties. An infantry regiment had an authorized strength of about 3,800 men; when it was time to regroup, the Ninth had only about 1,400 men left; the Thirty-eighth, 1,700; and the Twenty-third, 2,200.

LIEUTENANT CHARLEY HEATH

had never dared think he would make it out alive. But because he had gone out with the first group of tanks, he was one of the first to arrive, and he had been able to watch the other men from the division as the fortunate ones reached Sunchon. Every story seemed to be worse than the last, as the Chinese presence along The Gauntlet had grown stronger, and he heard stories about so many friends who had died that day. But there was one scene that he always remembered: his regimental commander, Colonel George Peploe, just standing there weeping. There had been moments when Peploe had seemed to those who served under him almost unbearably cocky, but this was a different man; it was as if he had been wounded, but all the wounds were on the inside. He was standing there crying, unable to stop, when one of his battalion commanders, Lieutenant Colonel Jim Skeldon, came over and held him and tried to steady him, more for emotional than physical reasons. But Peploe could not stop weeping, and then Skeldon, in the most tender of acts at the end of the most violent of days, took off his helmet and held it up to shield Peploe from the view of others, so no one else would be able to observe him crying. Though Peploe had lived when so many of his men died, it had clearly been a kind of death for him as well.

T

HE LEADERSHIP AT

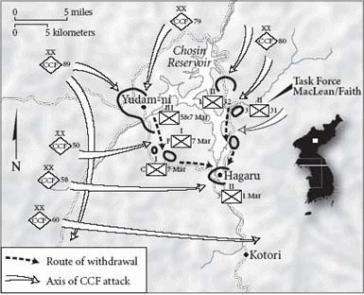

the top in the Second Division had been terrible. By contrast, because O. P. Smith had anticipated what the Chinese were going to do, the Marines were in much better shape. Their regiments were by no means perfectly connected, and still very vulnerable to being separated, and not nearly as close to their base at the port of Hungnam as Smith would have liked. The forward units near Yudam-ni were still far too exposed, and out on much more of a limb than Smith preferred, but at least they were somewhat better connected because he had stood up to Almond. Still, the vulnerability was unnerving. But at least they were not chasing wildly to the west to link up with the Eighth Army, as his orders had originally demanded. There was very little about their subsequent heroic march back to Hungnam that had to do with luck—most of it was the result of great individual courage and exceptional small-unit leadership—but on two points they were fortunate. First they benefited from the fact that the Chinese struck when they did, instead of waiting an additional day or two, by which time Ray Murray’s Fifth Marine Regiment might have been farther west, and thus more cut off from Litzenberg’s Seventh Regiment and the rest of the division; and second, that the Chinese had such poor communications and so little ability to adapt to the changing reality of battle. Had their communications been more modern, as Colonel Alpha Bowser later said, the First Marine Division would never have made it back from the Chosin Reservoir.

Their breakout from the Chosin Reservoir is one of the classic moments in their own exceptional history, a masterpiece of leadership on the part of their officers and of simple, relentless, abiding courage on the part of the ordinary fighting men—fighting a vastly larger force in the worst kind of mountainous terrain and unbearable cold that sometimes reached down to minus forty. Of all the battles in the Korean War, it is probably the most celebrated, deservedly so, and the most frequently written about. As the news reached Washington and then the country about the dilemma of the First Marines, seemingly cut off and surrounded by a giant force of Chinese, there was widespread fear that the division might be lost. Omar Bradley himself was almost certain they were lost. When the First Marines started the breakout, there were six Chinese divisions aligned against them, or roughly sixty thousand soldiers. In the two-week battle in which the Marines fought their way back to Hungnam, Smith believed that they had fought all-out against seven Chinese divisions and parts of three others. An estimated forty thousand Chinese were killed and perhaps another twenty thousand wounded. From November 27 to December 11, when the main battle with the Chinese began, the Marines lost 561 dead, 182 missing, 2,894 wounded, and another 3,600 who suffered from non-battle injuries, mostly frostbite.

17. B

REAKOUT FROM

C

HOSIN

R

ESERVOIR,

N

OVEMBER

2

7–DECEMBER

9, 1950

The small number of men missing in action compared to the number of men killed and wounded is testimony to the discipline of both the officers and the men. The division’s valor in fighting on island after island in the Pacific was well known long before the Korean War started. It had already distinguished itself, during the Naktong fighting, stopping breakthroughs whenever the North Koreans had momentarily penetrated the UN lines, and had performed with excellence after Inchon in the battle for Seoul. But this was its greatest challenge. Whether at that point any other American division could have made it out of what still seemed like an almost complete trap is doubtful.

“It was the strongest division in the world,” said one of its public information officers, Captain Michael Capraro. “I thought of it as a Doberman, a dangerous hound straining at the leash, wanting nothing more than to sink its fangs into the master’s enemy, preferably one with yellow skin.”

Some of the Army division commanders had been worried about the Chinese during the drive north, but most of them had been like Dutch Keiser and not acted on their fears. Smith had. He had, among other things, made clear to every officer in the division what he was to do when the Chinese struck. They would fight from the high ground, moving on paths if need be, but not anchored to the roads, as the Chinese hoped. They would use their artillery as their best weapon, the equalizer. They would move primarily during the day and they would try to button up at night. All of this meant they were prepared emotionally and strategically for the battle ahead, as most of the Army units had not been. The cold was if anything a more determined enemy than the Chinese. It was pervasive and never let up, and as if the natural cold registering on the thermometer up there on the Manchurian heights wasn’t bad enough, most of the time they were in a kind of Manchurian wind tunnel where the cold had a constant extra bite to it. The men came to look like Ancient Mariners who had sailed too close to the North Pole, all of them bearded; their beards, filled with ice shavings, told the story. The cold made men want to quit and give up—made it hard to want to fight and live for another day—and yet every day they kept fighting. Years later, when one of the senior NCOs visited Chesty Puller at his home outside of Washington, Puller greeted him and said, “Hey, Sarge, thawed out yet?”

They did not like to think of it as a retreat: it was not as if they had met an enemy moving at them from the North and pulled back to the South. A journalist had asked Smith during the fighting what he thought about the Marines’ retreat from Chosin and he had bristled. “Retreat, hell,” he had said, “we’re simply attacking in another direction.” The Chinese had, of course, blown the bridge at the Funchilin Pass after the Marines had crossed over it heading north, just as Smith had anticipated, and it seemed for a time like a death warrant—perhaps they

were

trapped there—but the Air Force had done a brilliant job of dropping the parts of a Treadway bridge in, and miraculously it worked; they were able to air-drop in enough sections, and somehow the engineers managed to put it in place. It allowed the Marines to go across when they returned south, a feat of engineering and ingenuity to match the courage of the men who were fighting. The First Marines had been completely surrounded, and in one of the great dramatic examples of sheer military strength they had fought their way through. At least four Chinese divisions were rendered combat ineffective during the battle.

There were many bleak military moments in the Korean War, but this was not one of them. In 2002, some fifty-one years after the battle, when Ed Simmons, who had fought there, wrote his history of the Chosin breakout he noted that in their 140-year history the Marines had received 294 Congressional Medals of Honor. Forty-two were awarded during the Korean War. Of that number, fourteen were awarded for action during the Chosin breakout, seven of them posthumously. Yet Smith’s leadership, his almost prophetic sense of the battle that was to come, never gained the admiration of the man whose corps he had saved. Almond still could not bring himself to praise Smith—for to admit what Smith had done was to admit his own awful miscalculations, and his blindness to the forces that had awaited him. “My general comment is that General Smith, ever since the Inchon landing and the preparation phase, was overly cautious executing any order that he ever received,” Almond said years later.

But in the end, for all of the unmatched heroism, it

was

a retreat—they had all gone too far north and they had been hit by a massive force and forced to move back. Smith and the Marines, proud though they were of their withdrawal, knew that. The one person who refused to admit that it had been a catastrophic mistake was MacArthur. The Marines subsequently prepared a history of what had happened and sent it to MacArthur, and he had objected to the use of the word “retreat.” “In all my experience I was never more satisfied with an operation than I was with this one,” Smith quoted him as saying. Then the Marine general added, “Now what are you going to do with a man like that?”

THE ASSAULT UPON

the Second Division in the west had been by contrast an epochal horror, moments of great courage dwarfed by the chaos and confusion and almost complete lack of leadership at the top. All in all what had happened in those days when the Chinese attacked the Army in the west, and in certain sectors of Tenth Corps, constituted, in the words of Dean Acheson (not an entirely disinterested bystander, for he by then seethed with hatred of MacArthur), the greatest defeat suffered by the American military since the battle of Bull Run in the Civil War. The men in the Second Division who made it out that day were always, some other veterans of the war thought, just a little different from most other veterans. Just as so many men who fought in Korea tended to be different when they came home, in the same way, the veterans of that one week, the week of the Chinese attack and the retreat down The Gauntlet, were just that much different from the other Korean veterans. There was very little bluster to them. They did not talk readily about their experiences, even to those who had also served in Korea. They seemed to recoil from those

who might praise them or talk of them as heroes. They thought of themselves only as survivors. As their units had been devastated, so too, in different ways, had many of them been damaged. Certainly something had been lost in many of them. One day they had been soldiers with countless buddies, part of an army that had gained the upper hand in a war that most of them hated, sure that a very difficult stretch in their lives had almost ended, and on a triumphant note at that. A week later, so many of their buddies were gone, often to indescribable fates, which all too often they had witnessed. Many of them bore not just the normal burden of the survivor, that uneasiness over why they had lived when someone they valued greatly and perhaps thought of as a better soldier had died, but a secret feeling, expressed to no one else, that over the six or seven days when so many of their friends had been killed or captured there had been some moment, maybe no more than a split second, when they might have been just a tiny bit braver and thus other men might have lived. Making it through had brought with it the immediacy of relief in living one more day, but often as they thought back on what had happened, what they had witnessed and done, there was the endless self-doubt as well.

DUTCH KEISER KNEW

from the moment the day was over that there was likely to be a need for a scapegoat, and that he was the most obvious choice. He was, in fact, relieved of his command four days later: an announcement from Tokyo indicated that he had a serious illness. A few days later Keiser called on Slam Marshall, the Army historian who was in Korea doing interviews for what became his book

The River and the Gauntlet,

and told him exactly what had happened. He had received a message from Eighth Army headquarters informing him “that he was ill with pneumonia and must report to a hospital in Tokyo.” Keiser knew instantly that they were about to tie the can for the defeat on him. He told Marshall he deeply resented being “the goat for MacArthur’s blunder.” So he drove down to Seoul to see Lev Allen, the Eighth Army chief of staff.

The conversation, he said, had gone like this:

Allen asked, “What the hell are you doing here? You’re ill with pneumonia.”

“You can see for yourself I don’t have pneumonia, so cut the bunk.”

“But are you going to comply with the order?”

“Yes, because it is an order, but I don’t want you to kid around with me.” Then Keiser started to leave.

Allen ventured one last line: “By the way, General Walker says he will take care of you with a job around his headquarters.”

“You tell General Walker to shove his job up his ass,” Keiser said.

But that was just the beginning. Dutch Keiser was the easiest of targets. In

the field, the entire military leadership was almost completely discredited. Walton Walker might not have liked the idea of the drive north to begin with, but the scope of the defeat underscored his own limitations as a field commander powerless in dealing with his superiors. He was sure that he was going to be relieved of his command, that he too would be a scapegoat. Ned Almond was protected politically in Tokyo as Walker was not, and his forces had been saved from complete destruction—but only because of O. P. Smith’s virtual insubordination. After Chesty Puller helped lead his regiment out to Hungnam, a

Time

magazine reporter had asked him what the great lesson of the battle was. “Never serve under Tenth Corps,” Puller had immediately answered. A few weeks later, when Matt Ridgway showed up in Korea to take command, he met with Smith, and the one thing Smith asked him was that the Marines never again be placed under Ned Almond’s command, a request to which Ridgway readily agreed.