The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume 4 (58 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume 4 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

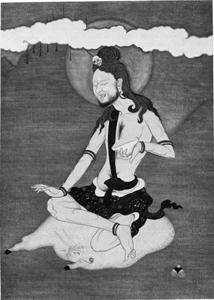

Naropa

.

PAINTING BY GLEN EDDY.

SEVEN

The Guru-Disciple Relationship

O

NE OF THE MOST

important figures in the history of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism is Naropa. Unlike some mothers whose names figure in the lineages of Buddhist spiritual transmission, Naropa was certainly a historical figure. Naropa is part of the Kagyü lineage of Tibetan Buddhism, being with his teacher Tilopa and his disciple Marpa the spiritual founder of that order. He is also recognized and venerated by all the Tibetan schools as the exemplary disciple.

The relationship between guru and disciple is of tremendous importance in Buddhist spiritual transmission. The relationship is not merely a matter of historical interest; it continues as an important factor up to the present day. This relationship is based on trust. But before such trust can be developed, there must be a period during which the guru tests his disciple. This process of testing is seen in a very complete way in the trials and difficulties Naropa was put through by his teacher Tilopa. A long time passed before Tilopa was willing to impart his knowledge to his disciple.

The testing of a disciple by the guru is, in a way, quite simple. A student comes to a teacher and asks for instruction. The teacher might well say, “Well, I don’t know very much. You’d better try some one else.” This is an excellent way of beginning the testing. The student might well go away, which would be a sign that he is not really very serious.

Because of the intimacy of the relationship between teacher and disciple, whatever happens between the two is vital to the teacher as well as the disciple. If something goes wrong, it reflects on the teacher as well as the disciple. The teacher must know better than to accept a student who is not ready to receive the teaching he has to offer. That is why before giving instruction, he will test the readiness, willingness, and capacity of the student to receive it. This means the student must become, to use the traditional image, a worthy vessel. And because of the intimacy of the prospective relationship, the student must also in his way test the teacher. He must scrutinize him to see if he is really able to transmit the teaching, if his actions tally with his words. If the conditions are not fulfilled on both sides, the relationship is not worthy to be engaged.

The tradition of the guru-disciple relationship has been handed down from ancient times in India as we see from the texts. The Tibetans took over this practice from the Indians and to this very day they enact it in the traditional manner. This close relationship has not only the work of passing on the oral teachings, but also of preserving the continuity of personal example.

Naropa was a worthy vessel. He was willing to undergo every kind of hardship in order to receive teaching. His hardships began with his search for a teacher. Naropa spent years in his search. And this search was actually part of the teaching his teacher imparted to him. Before Naropa saw Tilopa in his own form, he encountered him in a succession of strange guises. He saw him as a leprous woman, a butcher, and in many other forms. All these forms were reflections of Naropa’s own tendencies working within him, which prevented him from seeing Tilopa in this true nature, from seeing the true nature of the guru.

The term

guru

is an Indian word, which has now almost become part of the English language. Properly used, this term does not refer so much to a human person as to the object of a shift in attention which takes place from the human person who imparts the teaching to the teaching itself. The human person might more properly be called the

kalyanamitra

, or “spiritual friend.” Guru has a more universal sense. The kalyanamitra is one who is able to impart spiritual guidance because he has been through the process himself. He understands the problem of the student, and why the student has come to him. He understands what guidance he needs and how to give it.

To begin with, spiritual guidance can only be imparted in the context of our physical existence by a person who shares with us the situation of physically existing in this world. So the teacher first appears in the form of the kalyanamitra. Then, gradually, as his teaching takes root within us and grows, its character changes and it comes to be reflected in the teacher himself. In this way an identification of the guru and the kalyanamitra takes place. But it is important that the guru be recognized and accepted as the guru and not confounded with the kalyanamitra in the manner of a mere personality cult. It is not a simple equation between the guru and the kalyanamitra. Still the kalyanamitra must be recognized as one able to give the knowledge which the student desires, which he needs, in fact, as a vital factor in his growth.

Here again we can refer to the example of Naropa. In the beginning, Naropa failed to understand the process in which he was involved. The inner growth that was already being prepared and taking root in him was still obscured by the many preconceptions he had. He continued to see the manifestations of his guru in the light of his ordinary conceptions, rather than understanding that they were symbols presenting the opportunity of breaking through preconceptions. These manifestations gave him the opportunity to be himself, rather than his idea of himself as a highly capable person.

We must remember that Naropa came from a royal family. His social prestige was great and he had become, in addition, a renowned pandit. And so in the process of trying to relate to his guru, his pride came into play. He felt that, as a person already renowned for his understanding, he should have all the answers already. But this was not the case. Only after the testing period did any real answers begin to emerge. This testing process actually effected the removal of his preconceptions. It was actually the teaching itself in the most concrete terms. No amount of words would have achieved the result that came about through his exposure to the rough treatment, the shock treatment, to which Tilopa subjected him. At the very moment in which he would think that at last he had understood, that at last these endless trials were over—at that very moment he would realize that he had again failed to see.

In the whole process of learning that is involved here, and one can say that the Buddhist way is a way of learning, there is a continual oscillation between success and failure. Sometimes things go smoothly. This is a fine thing; but it may also be a very great danger. We may become too self-sure, too confident that everything is going to come out as we would like it. Complacency builds up. So sometimes the failures that arise are very important in that they make us realize where we went wrong and give us a chance to start over again. Out of this experience of failure, we come to see things anew and afresh.

This oscillation between success and failure brings the sense of a way, a path; and here we touch upon the importance of the Buddhist tradition of the way. Buddhism has never claimed to be other than a way. The Buddha himself was only the teacher who showed other people the way which he himself had to travel, whatever the vicissitudes of success and failure. But it is always true that if a person fails, he can start again. If the person is intelligent, he will learn from the mistakes he has made. Then these mistakes will become ways of helping him along, as happened in the case of Naropa. Quite often Tilopa asked him to do things which were quite out of the question from Naropa’s ordinary point of view, which quite went against the grain of his conventional frame of reference. But this was very much to the point. Conformity to the accepted way of looking at things would bring nothing. The point was to gain a new vision.

If we come to a new vision, a new way of looking at things, its mode of application may quite well be different from what is commonly accepted. This has always been the case with the great spiritual leaders of mankind, wherever we look. These people have broadened and widened our horizon. Through their action we have experienced the satisfaction of growing out of the narrowness of the ordinary world into which we happen to have been born.

When Naropa had shown that he was a person worthy of receiving instruction, the whole pattern we have been describing changed. Tilopa then showed himself the kindest person that could be imagined. He withheld nothing that Naropa wished of him. There is a Sanskrit expression,

acharya mushti

, which means the “closed fist.” This is an expression that has often been applied to gurus who withhold the teaching. At a certain point, if the teacher withholds instruction, it is a sign that he is unsure of himself. But this was certainly not now the case with Tilopa. He gave everything that he had to his disciple.

This is the manner of continuing the teacher-disciple relationship. At a certain point the teacher transmits the entirety of his understanding to a disciple. But that the disciple must be worthy and brought to a state of complete receptivity is one of the messages of Naropa’s life. And so, in his turn, Naropa led his disciple Marpa through the same preparatory process, and Marpa led his disciple Milarepa. Milarepa’s biography tells us that Marpa had him build a house out of stone. He had hardly finished the house when Marpa told him to tear the house down and begin over again. This happened again and again. We need not ask ourselves whether this is a historical fact. The symbolic message is quite plain. Marpa asked him to do something and Milarepa reacted with pride, feeling that he could do it. Milarepa did it his way without waiting for the instruction. Naturally, the results were not satisfactory and there was no alternative but to have him tear it down and build again from the beginning.

Here we see another aspect of the guru-disciple relationship. The disciple must start at the beginning. And this comes almost inevitably as a blow to his pride, because he almost always feels that he understands something already. It is usually a very long time before this pride is broken down and real receptivity begins to develop.

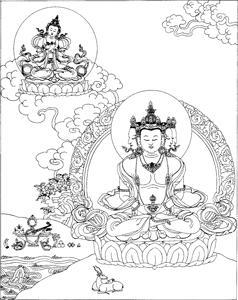

Mahavairochana

(foreground)

and Vajradhara

(background).

DRAWING BY TERRIS TEMPLE.

EIGHT

Visualization

O

N THE DISK OF THE

autumn moon, clear and pure, you place a seed syllable. The cool blue rays of the seed syllable emanate immense cooling compassion that radiates beyond the limits of sky or space. It fulfills the needs and desires of sentient beings, bringing basic warmth so that confusions may be clarified. Then from the seed syllable you create a Mahavairochana Buddha, white in color, with the features of an aristocrat—an eight-year-old child with a beautiful, innocent, pure, powerful, royal gaze. He is dressed in the costume of a medieval king of India. He wears a glittering gold crown inlaid with wish-fulfilling jewels. Part of his long black hair floats over his shoulders and back; the rest is made into a topknot surmounted by a glittering blue diamond. He is seated cross-legged on the lunar disk with his hands in the meditation mudra holding a vajra carved from pure white crystal.

Now what are we going to do with

that?

The picture is uncomplicated; at the same time it is immensely rich. There is a sense of dignity and also a sense of infanthood. There is a purity that is irritatingly pure, irritatingly cool. As we follow the description of Mahavairochana, perhaps his presence seems real in our minds. Such a being could actually exist: a royal prince, eight years of age, who was born from a seed syllable. One feels good just to think about such a being.

Mahavairochana is the central symbol in the first tantric yana, the kriyayogayana. He evokes the basic principle of kriyayoga—immaculateness, purity. He is visualized by the practitioner as part of his meditation.

In the kriyayogayana, since one has already discovered the transmutation of energy, discovered all-pervading delight, there is no room for impurity, no room for darkness. The reason is that there is no doubt. The rugged, confused, unclean, impure elements of the struggle with samsara have been left far behind. Finally we are able to associate with that which is pure, clean, perfect, absolutely immaculate. At last we have managed to actualize tathagatagarbha, buddha nature. We have managed to visualize to actualize, to formulate a most immaculate, pure, clean, beautiful, white, spotless principle.