The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five (27 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

S:

When the thought-lineage transmission occurs, there’s this openness, this gap. Is that in itself the transmission?

TR:

Yes, that’s it. Yes, that’s it. And there is also the environment around that, which is somewhat global, almost creating a landscape. In the midst of that, the gap is the highlight.

S:

It seems that we constantly find ourselves in situations of openness and slip out. What is the benefit of going back to it? Is it kind of a practice, seeing that space so you can go back to it?

TR:

Well, you see, you can’t re-create that. But you can create your own abhisheka every moment. After the first experience. After that, you can develop your own inner guru; and you create your own abhisheka, rather than trying to memorize what happened already in that past. If you keep going back to that moment in the past, it becomes kind of a special treasure, which doesn’t help.

S:

Doesn’t help?

TR:

Doesn’t help.

S:

But it’s necessary to have that experience—

TR:

That experience is a catalyst. For example, if you have once had an accident, each time after that when you drive with some crazy driver, you have a really living idea of an accident. You have the sense that you might die at any moment, which is true.

Student:

We are talking of openness as a very special situation taking place in transmission, and yet, it seems that it’s spontaneously there, subliminally and very often here and there and everywhere. It’s naturally behind neurosis as it passes through you, kind of passing with it. Can you speak more about the situation of the naturalness of the openness?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

It seems that at this point if we try to be more specific in describing the details, it won’t particularly help. It would be like creating special tactics and telling you how to reproduce them—like trying to be spontaneous by textbook—which doesn’t seem to do any good. Probably we have to go through some kind of a trial period.

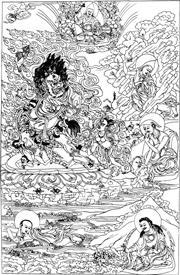

Senge Dradrok.

Notes

S

EMINAR

I

Chapter 5

1

. Bön (often written “Pön”) is an indigenous pre-Buddhist religion of Tibet. [Ed.]

S

EMINAR

II

Chapter 1

2

. “Simultaneous birth” is a reference to the tantric notion of coemergence, or coemergent wisdom (Tib.

ihenchik kyepe yeshe

). Samsara and nirvana arise together, naturally giving birth to wisdom. [Ed.]

Chapter 2

3

. This does not contradict Trungpa Rinpoche’s description in the main body of this talk, of the dharmakaya as unconditioned. Although conditioned by a sense of pregnancy, the dharmakaya, as he tells us earlier, also remains unaffected by any contents, thus providing the continual possibility of a glimpse of unconditioned mind. Cf. Rinpoche’s answer to the question about karma and the dharmakaya, in chapter 3. [Ed.]

Chapter 3

4

. Herbert V. Guenther, trans.,

The Life and Teaching of Naropa

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963).

Chapter 4

5

. Francesca Fremantle and Chögyam Trungpa, trans.,

The Tibetan Book of the Dead: The Great Liberation through Hearing in the Bardo

(Boston and London: Shambhala, 1987).

Chapter 6

6

. This is a quotation from the author’s

Sadhana of Mahamudra,

a liturgy practiced by his students. [Ed.]

I

LLUSION

’

S

G

AME

The Life and Teaching of Naropa

EDITED BY

S

HERAB

C

HÖDZIN

K

OHN

Editor’s Foreword

T

HIS BOOK IS

composed of two seminars by the Vidyadhara, the Venerable Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, on the life and teachings of Naropa. Naropa, an Indian of the eleventh century, was one of the Vidyadhara’s own spiritual forefathers and a seminal figure for the vajrayana Buddhism of Tibet. The Vidyadhara gave a number of seminars on Naropa, each with its own flavor and emphasis. The editor has had to make a more or less arbitrary selection from them for this volume (New York, January 1972, four talks; Tail of the Tiger, Vermont, 1973, six talks). Future volumes, we hope, will complete the availability to the public of the Vidyadhara’s teaching on the very profound subject matter surrounding the life of Naropa.

“Great Vajradhara, Telo, Naro, Marpa, Mila; lord of dharma, Gampopa. . . .” So begins the supplication to the lineage of enlightened teachers of the Kagyü, one of the four main orders of Buddhism in Tibet. Vajradhara is the dharmakaya buddha, the ultimate repository of awakened mind. Telo is Tilopa, a great Indian siddha, Naropa’s guru, the first human in the lineage. Naro is Naropa, who became the guru of Marpa, the first Tibetan in the lineage. Marpa’s disciple was Mila, the renowned Tibetan yogi usually known as Milarepa (Mila the cotton clad). Milarepa’s leading disciple, Gampopa, founded the monastic order of the Kagyü, the various branches of which have been headed by Gampopa’s successors for the last nine hundred years.

In the vajrayana Buddhism of Tibet, the central event, which remains timelessly new through the generations, is the transmission of the awakened state of mind from guru to disciple through a meeting of minds. As the awakened state itself is independent of word, concept, or thought, the transmission of it is beyond process. Nevertheless it happens in people’s lives, and an extraordinarily demanding process of preparation seems to be needed for students to reach the spiritual nakedness that enables them to open directly to the guru’s mind. This process, as we see from Naropa’s story, is one that requires of the student an extreme level of self-surrender and in which the teacher sometimes resorts to extremely brutal means to break him and strip him down. Doubtless to the workaday world, such a process, with its outrageous suffering, may seem insane. Yet, seen with the greater vision of enlightenment—here spoken of in terms of mahamudra, the “great seal”—this process is the utmost expression of compassion and sanity. The tale of how Naropa came into direct communication with Tilopa and received from him the transmission of awakened mind became a paradigm for the later tradition of vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet, which arose out of their relationship.

Naropa’s story makes it possible to delineate in very concrete terms the various levels of spiritual development that lead up to the possibility of meeting the guru’s mind. This is the main thrust of the Vidyadhara’s presentation to Western students—making them see themselves and their potentialities in Naropa and his journey. In this manner he opens to them the path of devotion and surrender to the guru as the embodiment and spokesman of reality.

The Vidyadhara deals only briefly here with the formal mahamudra teachings and other tantric teachings associated with Naropa’s name, notably, the six dharmas of Naropa (Tib.

naro chödruk

), or six Naropa yogas, as they are sometimes called. But in his concise descriptions, particularly in the later part of the book, he catches each one by its experiential essence, conveying in a few simple words an insight that students might well seek in vain elsewhere through hundreds of pages of text or many hours of oral teaching.

The students to whom the Vidyadhara gave these talks were asked to read

The Life and Teaching of Naropa,

the twelfth-century biography translated from Tibetan by the eminent scholar Herbert V. Guenther (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1986). Reading this book might be a help for readers of the present volume. Nevertheless, the summary of it that follows and the citations and references in the text convey the essentials. Moreover, occasional references and descriptions by the Vidyaditor’s foreword dhara reveal that he was sometimes referring in his own mind to at least one other version of Naropa’s life story.

Naropa lived in northern India in the eleventh century. He was the only son of a royal family. From an early age, he devoted himself singlemindedly to spiritual matters. His mind was filled with compassion for beings, and his primary interest was the study and practice of the buddhadharma. In his youth, in view of his parents’ strong desire for the continuity of their royal line, Naropa consented to marry. However, after eight years he was once more overcome by his desire to devote himself exclusively to the dharma. His wife, Niguma, agreed to a divorce and became his disciple (and later a great teacher). Naropa entered the great Buddhist monastic university of Nalanda. There he greatly developed his intellectual powers and became extremely learned. So great were his intellectual powers and erudition that he was elevated to the abbacy of Nalanda. He became renowned as the premier teacher of Buddhism of his time.

At this point in his life (at around the age of forty), the event occurred that was to make Naropa of interest to the tantric tradition. One day, as he was reading with his back to the sun (a symbolic description of his spiritual relationship to reality at that time), he had a vision of a very ugly woman, who told him he understood only the words in his book, not their real meaning. She also revealed that the only way to discover the real meaning was to seek a guru, her brother Tilopa (see part one, chapter 1 for a quotation of this passage). Over the sustained and impassioned objections of the masters and students of Nalanda, who begged Naropa not to leave and deprive them of their guiding light, Naropa departed from the great university and began his lonely journey in search of Tilopa.

This journey turned out to be arduous and daunting in the extreme. Naropa encountered, instead of Tilopa himself, eleven hideous visions (see part one, chapter 2 for a quotation describing this part of the story). Naropa was about to kill himself when Tilopa finally appeared and accepted him as his student. Tilopa showed Naropa a series of symbols, which Naropa understood. Tilopa then sat motionless for a year. At the end of a year, Tilopa made a slight movement, which provided a pretext for Naropa to prostrate and ask for teaching. Tilopa required him to leap from the roof of a tall temple building. Naropa’s body was crushed. He suffered immense pain. Tilopa healed him with a touch of his hand, then gave him instruction.

This pattern was repeated eleven more times. Eleven more times Tilopa remained either motionless or aloof for a year; then Naropa prostrated and asked for teaching. Tilopa caused him to throw himself into a fire where he was thoroughly burned, to be beaten nearly to death, have his blood sucked out by leeches, be pricked with flaming splinters, run till he nearly expired, be thoroughly beaten again, be beaten nearly to death once more, suffer intolerably in a relationship with a woman, give his consort to Tilopa and watch him maltreat her, and cut off his arms and legs and present them to Tilopa in the form of a mandala. After each of these torments, Tilopa restored him with a touch of his hand and bestowed a precious teaching. The teachings gained in this way, including the renowned six dharmas of Naropa, are those that have been passed down for a millennium in the Kagyü and other lineages.

After further tasks and trials and teachings, finally the transmission of mahamudra through the meeting of the minds took place completely. Tilopa then instructed Naropa to bring benefit to beings. Later, as Tilopa foresaw, Marpa crossed the Himalayas from Tibet, found Naropa, and became his disciple. When Naropa had completed his teachings to Marpa, he prophesied to him that he would have a great spiritual son, Milarepa. At that time, Naropa nodded three times in the direction of Tibet. At the same time, all the trees of that region of northern India (Pullahari) bowed three times toward Tibet. They still remain inclined in that direction today.

The Vidyadhara’s commentaries on the life of Naropa go far to illuminate the nature of the spiritual path, a subject that is still scarcely understood. In this way they provide a fundamental background for those seeking to fathom his thought. They are especially helpful in explaining why, throughout the nearly twenty years that he taught in the West, he continued to warn against and castigate lukewarm approaches to spirituality that seek to integrate it “reasonably” into conventional life. He decried as spiritual materialism the use of spiritual truths and practices as a means to promote happiness, health, success in society, and other comforts of ego. From the moment Naropa caught a glimpse of the ugly woman, these are precisely the things to which he had to give up his attachment—down to the last trace. Thus, in offering commentary on the life of Naropa, the Vidyadhara can teach us directly of the genuine spirituality—raw and rugged, as he often described it—that he himself abandoned all comforts in order to instill.