The Coming of the Third Reich (19 page)

Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

The second arm of the ‘Weimar coalition’, the German Democratic Party, was a somewhat more enthusiastic participant in government, serving in virtually all the cabinets of the 1920s. It had, after all, been a Democrat, Hugo Preuss, who had been the principal author of the much-maligned Weimar constitution. But although they won 75 seats in the election of January 1919, they lost 36 of them in the next election, in June 1920, and were down to 28 seats in the election of May 1924. Victims of the rightward drift of middle-class voters, they never recovered.

28

Their response to their losses after the elections of 1928 was disastrous. Led by Erich Koch-Weser, leading figures in the party joined in July 1930 with a paramilitary offshoot of the youth movement known as the Young German Order and some individual politicians from other middle-class parties, to transform the Democrats into the State Party. The idea was to create a strong centrist bloc that would stem the flow of bourgeois voters to the Nazis. But the merger had been precipitate, and closed off the possibility of joining together with other, larger political groups in the middle. Some, mostly left-wing Democrats, objected to the move and resigned. On the right, the Young German Order’s move lost it support among many of its own members. The electoral fortunes of the new party did not improve, and only 14 deputies represented it in the Reichstag after the elections of September 1930. In practice the merger meant a sharp shift to the right. The Young German Order shared the scepticism of much of the youth movement about the parliamentary system, and its ideology was more than tinged with antisemitism. The new State Party continued to keep the Social Democratic coalition in Prussia afloat until the state elections of April 1932, but its aim, announced by the historian Friedrich Meinecke, was now to achieve a shift in the balance of political power away from the Reichstag and the states and towards a strong, unitary Reich government. Here too, therefore, a steady erosion of support pushed the party to the right; but the only effect of this was to wipe out whatever distinguished it from other, more effective political organizations that were arguing for the same kind of thing. The State Party’s convoluted constitutional schemes not only signalled its lack of political realism, but also its weakening commitment to Weimar democracy.

29

Of the three parties of the. ‘Weimar coalition’, only the Centre Party maintained its support throughout, at around 5 million votes, or 85 to 90 seats in the Reichstag, including those of the Bavarian People’s Party. The Centre Party was also a key part of every coalition government from June 1919 to the very end, and with its strong interest in social legislation probably had as strong a claim to have been the driving force behind the creation of Weimar’s welfare state as the Social Democrats did. Socially conservative, it devoted much of its time to fighting pornography, contraception and other evils of the modern world, and to defending Catholic interests in the schools system. Its Achilles heel was the influence inevitably wielded over it by the Papacy in Rome. As head of the Catholic Church, Pope Pius XI was increasingly worried by the advance of atheistic communists and socialists during the 1920s. Together with his Nuncio in Germany, Eugenio Pacelli, who subsequently became Pope Pius XII, he profoundly distrusted the political liberalism of many Catholic politicians and saw a turn to a more authoritarian form of politics as the safest way to preserve the Church’s interests from the looming threat of the godless left. This led to his conclusion of a Concordat with Mussolini’s Fascist regime in Italy in 1929 and later on to the Church’s support for the ‘clerico-fascist’ dictatorship of Engelbert Dollfuss in the Austrian civil war of 1934, and the Nationalists under General Franco in the Spanish Civil War that began in 1936.

30

With such signals emanating from the Vatican even in the 1920s, the prospects for political Catholicism in Germany were not good. They became markedly worse in December 1928, when a close associate of Papal Nuncio Pacelli, Prelate Ludwig Kaas, a priest who was also a deputy in the German Reichstag, succeeded in being elected leader of the Centre Party as a compromise candidate during a struggle between factions of the right and left over the succession to the retiring chairman, Wilhelm Marx. Under Pacelli’s influence, however, Kaas veered increasingly towards the right, pulling many Catholic politicians with him. As increasing disorder and instability began to grip the Reich in 1930 and 1931, Kaas, now a frequent visitor to the Vatican, began to work together with Pacelli for a Concordat, along the lines of the agreement recently concluded with Mussolini. Securing the future existence of the Church was paramount in such a situation. Like many other leading Catholic politicians, Kaas considered that this was only really possible in an authoritarian state where police repression stamped out the threat from the left. ‘Never’, declared Kaas in 1929, ‘has the call for leadership on the grand scale echoed more vividly and impatiently through the soul of the German people as in the days when the Fatherland and its culture have been in such peril that the soul of all of us has been oppressed.’

31

Kaas demanded among other things much greater independence for the executive from the legislature in Germany. Another leading Centre Party politician, Eugen Bolz, Minister-President of Württemberg, put it more bluntly when he told his wife early in 1930: ‘I have long been of the opinion that the Parliament cannot solve severe domestic political problems. If a dictator for ten years were a possibility - I would want it.’

32

Long before 30 January 1933, the Centre Party had ceased to be the bulwark of Weimar democracy that it had once been.

33

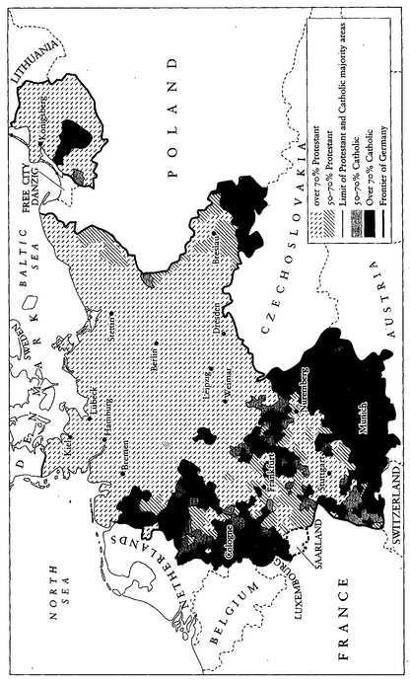

Map 5. The Religious Divide

Thus, even the major political props of democracy in the Weimar Republic were crumbling by the end of the 1920s. Beyond them, the democratic landscape was even more desolate. No other parties offered serious support to the Republic and its institutions. On the left, the Republic was confronted with the mass phenomenon of the Communists. In the revolutionary period from 1918 to 1921 they were a tightly knit, elite group with little electoral support, but when the Independent Social Democrats, deprived of the unifying factor of opposition to the First World War, fell apart in 1922, a large number of them joined the Communists, who thus became a mass party. Already in 1920 the combined forces of the Independent Social Democrats and the Communists won 88 seats in the Reichstag. In May 1924 the Communists won 62 seats, and, after a small drop later in the year, they were back to 54 in 1928 and 77 in 1930. Three and a quarter million people cast their votes for the party in May 1924 and over four and a half million in September 1930. These were all votes for the destruction of the Weimar Republic.

Through all the twists and turns of its policies during the 1920s, the Communist Party of Germany never deviated from its belief that the Republic was a bourgeois state whose primary purposes were the protection of the capitalist economic order and the exploitation of the working class. Capitalism, they hoped, would inevitably collapse and the ‘bourgeois’ republic would be replaced by a Soviet state along Russian lines. It was the duty of the Communist Party to bring this about as soon as possible. In the early years of the Republic this meant preparing for an ‘October revolution’ in Germany by means of an armed revolt. But, after the failure of the January uprising in 1919 and the even more catastrophic collapse of plans for an uprising in 1923, this idea was put on hold. Steered increasingly from Moscow, where the Soviet regime, under the growing influence of Stalin, tightened its financial and ideological grip on Communist parties everywhere in the second half of the 1920s, the German Communist Party had little option but to swing to a more moderate course in the mid-1920s, only to return to a radical, ‘leftist’ position at the end of the decade. This meant not only refusing to join with the Social Democrats in the defence of the Republic, but even actively collaborating with the Republic’s enemies in order to bring it down.

34

Indeed, the party’s hostility to the Republic and its institutions even caused it to oppose reforms that might lead the Republic to become more popular among the working class.

35

This implacable opposition to the Republic from the left was more than balanced by rabid animosity from the right. The largest and most significant right-wing challenge to Weimar was mounted by the Nationalists, who gained 44 Reichstag seats in January 1919,71 in June 1920, 95 in May 1924 and 103 in December 1924. This made them larger than any other party with the exception of the Social Democrats. In both elections of 1924 they won around 20 per cent of the vote. One in five people who cast their ballot in these elections thus did so for a party that made it clear from the outset that it regarded the Weimar Republic as utterly illegitimate and called for a restoration of the Bismarckian Reich and the return of the Kaiser. This was expressed in many different ways, from the Nationalists’ championing of the old Imperial flag, black, white and red, in place of the new Republican colours of black, red and gold, to their tacit and sometimes explicit condoning of the assassination of key Republican politicians by armed conspiratorial groups allied to the Free Corps. The propaganda and policies of the Nationalists did much to spread radical right-wing ideas across the electorate in the 1920s and prepare the way for Nazism.

During the 1920s, the Nationalists were a partner in two coalition governments, but the experience was not a happy one. They resigned from one government after ten months, and when they came into another cabinet half-way through its term of office, they were forced to make compromises that left many party members deeply dissatisfied. Severe losses in the elections of October 1928, when the Nationalists’ representation in the Reichstag fell from 103 seats to 73, convinced the right wing of the party that it was time for a more uncompromising line. The traditionalist party chairman Count Westarp was ousted and replaced by the press baron, industrialist and radical nationalist Alfred Hugenberg, who had been a leading light of the Pan-German movement since its inception in the 1890s. The Nationalist Party programme of 1931, drafted under Hugenberg’s influence, was distinctly more right wing than its predecessors. It demanded among other things the restoration of the Hohenzollern monarchy, compulsory military service, a strong foreign policy directed at the revision of the Treaty of Versailles, the return of the lost overseas colonies and the strengthening of ties with Germans living in other parts of Europe, especially Austria. The Reichstag was to retain only a supervisory role and a ‘critical voice’ in legislation, and to be joined by ’a representational body structured according to professional rankings in the economic and cultural spheres’ along the lines of the corporate state being created at the time in Fascist Italy. And, the programme went on, ‘we resist the subversive, un-German spirit in all forms, whether it stems from Jewish or other circles. We are emphatically opposed to the prevalence of Jewdom in the government and in public life, a prevalence that has emerged ever more continuously since the revolution.’

36

Under Hugenberg, the Nationalists also moved away from internal party democracy and closer to the ‘leadership principle’. The party’s new leader made strenuous efforts to make party policy on his own and direct the party’s Reichstag delegation in its votes. A number of Reichstag deputies opposed this, and a dozen of them split off from the party in December 1929 and more in June 1930, joining fringe groups of the right in protest. Hugenberg allied the party with the extreme right, in an attempt to get a popular referendum to vote against the Young Plan, an internationally agreed scheme, brokered by the Americans, for the rescheduling of reparations payments, in 1929. The failure of the bitterly fought campaign only convinced Hugenberg of the need for even more extreme opposition to Weimar and its replacement by an authoritarian, nationalist state harking back to the glorious days of the Bismarckian Empire. None of this worked. The Nationalists’ snobbery and elitism prevented them from winning a real mass following and rendered their supporters vulnerable to the blandishments of the truly populist demagoguery practised by the Nazis.

37

Less extreme, but only marginally less vehemently opposed to the Republic, was the smaller People’s Party, the heir of the old pro-Bismarckian National Liberals. It won 65 seats in the 1920 election and stayed around 45 to 50 for the rest of the decade, attracting about 2.7 to 3 million votes. The party’s hostility to the Republic was partly masked by the decision of its leading figure, Gustav Stresemann, to recognize political realities for the moment and accept the legitimacy of the Republic, more out of necessity than conviction. Although he was never fully . trusted by his party, Stresemann’s powers of persuasion were considerable. Not least thanks to his consummate negotiating skills, the People’s Party took part in most of the Republic’s cabinets, unlike the Nationalists, who stayed in opposition for the greater part of the 1920s. Yet this meant that the majority of governments formed after the initial phase of the Republic’s existence contained at least some ministers who were dubious, to say the least, about its right to exist. Moreover, Stresemann, already in difficulties with his party, fell ill and died in October 1929, thus removing the principal moderating influence from the party’s leadership.

38

From this point on it, too, gravitated rapidly towards the far right.