The Coming of the Third Reich (38 page)

Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

III

The years 1927-8 saw the creation of a new basic structure for the Nazi Party across the country. In 1928 the Party Regions were realigned to follow the boundaries of the Reichstag constituencies - only 35 of them, all very large, to conform to Weimar’s system of proportional representation by party list - to signal the primacy of their electoral functions. Within a year or so of this, a new intermediate organizational layer of districts (Kreise) had been created between the Regions and the local branches. A new generation of younger Nazi activists played the most prominent role at these levels. They pushed aside the generation left over from prewar Pan-German and conspiratorial organizations, and outnumbered those who had taken an active part in the Free Corps, the Thule Society and similar groups. But it is important to remember that even the older generation of leading Nazis were themselves still young men, particularly when compared with the greying, middle-aged politicians who led the mainstream political parties. In 1929 Hitler was still only 40, Goebbels 32, Goring 36, Hess 35, Gregor Strasser 37. Their role remained crucial, especially in providing leadership and inspiration to the younger generation.

Goebbels, for example, made his reputation above all as Regional Leader of Berlin, where his fiery speeches, his incessant activity, his outrageous provocations of the Nazis’ opponents, and his calculated staging of street-fights and meeting-hall brawls to gain the attention of the press won the Party a mass of new adherents. More publicity accrued from the Berlin Party’s aggressive and extremely defamatory campaigns against figures such as the Berlin deputy police chief Bernhard Weiss, whose Jewish descent Goebbels drew attention to through calling him ‘Isidor’ - an entirely made-up name, commonly used by antisemites for Jews, and borrowed on this occasion, ironically, from the Communist press.

100

Goebbels’s violence and extremism earned the Nazi Party in Berlin an eleven-month ban from the city’s Social Democratic authorities in 1927- 8; but they also won him the allegiance and admiration of younger activists such as the 19-year-old Horst Wessel, a pastor’s son who had abandoned his university law studies for the world of the paramilitaries, most recently the brownshirts. ‘What this man has shown in oratorical gifts and talent for organization’, he wrote of ’our Goebbels’ in 1929, ‘is unique... The S.A. would have let itself be hacked to bits for him.’

101

A great deal of in-fighting took place over key posts in the Party organization at a local and regional level. On the whole, however, as Max Amann told one local activist towards the end of 1925, Hitler

takes the view on principle that it is not the job of the Party leadership to ‘install’ branch leaders. Herr Hitler takes the view today more than ever that the most effective fighter in the National Socialist movement is the man who pushes his way through on the basis of his achievements as a leader. If you yourself write that you enjoy the trust of almost all the members in Hanover, why don’t you then take over the leadership of the branch?

102

In this way, Hitler thought, the most ruthless, the most dynamic and the most efficient would rise to positions of power within the movement. He was later to apply the same principle in running the Third Reich. It helped ensure that the Nazi Party at every level became ceaselessly active, constantly marching, fighting, demonstrating, mobilizing. Yet this did not bring immediate rewards. By the end of 1927 the Party still had only some 75,000 members and a mere seven deputies elected to the Reichstag. The hopes of men like Strasser and Goebbels that it would be able to win over the industrial working class had proved to be illusory.

103

Recognizing the difficulties of breaking into the Social Democratic and Communist heartlands, the Nazis turned instead to rural society in Protestant north Germany, where rising peasant discontent was spilling over into demonstrations and campaigns of protest. The contradictory effects of inflation and stabilization on the farming community had merged into a general crisis of agriculture by the late 1920s. While large landowners and farmers had bought machinery on hire purchase and were thus able to modernize at very little real cost to themselves, peasants tended to hoard money and so lost it, or spent it on domestic goods and so gained no benefit for their businesses. After the inflation, government measures to ease credit restrictions on agriculture to help recovery only made things worse, as peasants borrowed heavily to make good their losses, expecting a fresh round of inflation, then found they were unable to pay the money back because prices were declining instead of rising. Bankruptcies and foreclosures were already rising in number towards the end of the 1920s, and small farmers were turning to the extreme right in their despair.

104

Larger farmers and big landowners were suffering from the downturn in agricultural prices, and were unable to pay what they regarded as excessively high taxes to support the Weimar welfare state.

105

Both the Prussian and the Reich governments had tried to alleviate the situation by tariffs, subsidies, import controls and the like, but all these proved wholly inadequate to the situation.

106

Farmers of all types had modernized, mechanized and rationalized in order to try and deal with the agricultural depression since the early 1920s, but it was not enough. Pressure for high import tariffs on foodstuffs grew more insistent as the farming community began to see this as the only way to protect their income. In this situation, the Nazis’ promise of a self-sufficient, ‘autarchic’ Germany, with foreign food imports more or less banned, seemed increasingly attractive.

107

Realizing that they were winning support in rural areas in the Protestant north without really trying, the Nazis accelerated the shift in their propaganda from the urban working class to other sectors of the population. Now the Party turned its attention to rural districts and began to mount serious recruiting drives in areas like Schleswig-Holstein and Oldenburg.

108

Hitler retreated still further from the ‘socialist’ orientation of the Party in north Germany, and even ‘clarified’, or in other words amended, Point 17 of the Party Programme, on 13 April 1928, in order to reassure small farmers that its commitment to ‘the expropriation of land for communal purposes without compensation’ referred only to ‘Jewish companies which speculate in land’.

109

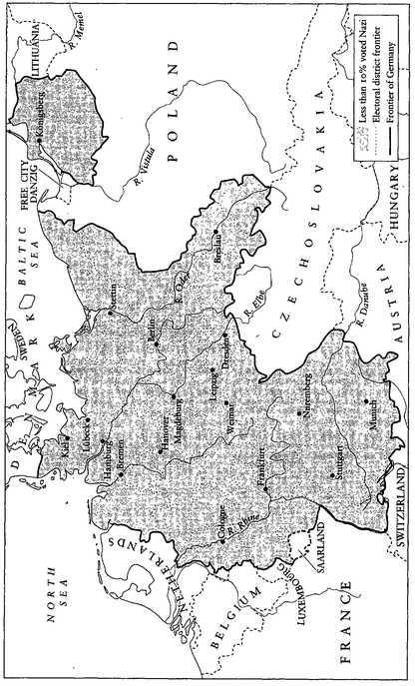

The Nazis lost 100,000 votes in the Reichstag elections of May 1928, and with a mere 2.6 per cent of the vote were only able to get 12 deputies into the legislature, among them Gottfried Feder, Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Goring and Gregor Strasser. None the less, in some rural areas of the Protestant north they did much better. While they could only manage 1.4 per cent in Berlin and 1.3 per cent in the Ruhr, for example, they scored no less than 18.1 and 17.7 per cent respectively in two counties in Schleswig-Holstein. A vote of 8.1 per cent in another area inhabited by discontented Protestant small farmers, namely Franconia, reinforced the feeling that, as the Party newspaper put it on 31 May, ‘the election results from the rural areas in particular have proved that with a smaller expenditure of energy, money and time, better results can be achieved there than in the big cities’.

110

Map 8. The Nazis in the Reichstag Election of 1928

The Party soon revamped its propaganda appeal to the farming community, telling them that it would create a special position for them in the Third Reich. Farmers of all kinds would be granted a ‘corporation’ of their own, in which they would work together in harmony and with the full backing of the state. Refractory farmhands, many of whom were active in the Social Democratic Party, would be brought to heel, and labour costs would at last come under tight control. After years of unsuccessful, sometimes violent protest, farmers in Schleswig-Holstein flocked to the support of the Nazi Party. It did no harm to its cause that the Party was led locally by members of the farming community, nor that it laid unmistakeable stress on an ideology of ‘blood and soil’ in which the peasant would be the core of the national identity. Even some of the larger landowners, traditionally identified with the Nationalists, were convinced. The Nazi Party’s support amongst middling and small landowners skyrocketed. Soon, farmers’ sons were providing the manpower for stormtrooper units being despatched to fight the Communists in the big cities.

111

Thus, the new strategy soon began to bear fruit. The Party’s membership grew from 100,000 in October 1928 to 150,000 a year later, while in local and state elections its vote now began to increase sharply, rising to 5 per cent in Saxony, 4 per cent in Mecklenburg and 7 per cent in Baden. In some rural areas of Protestant Saxony it nearly doubled its share of the vote, increasing, for example, from 5.9 per cent in the Schwarzenberg district in 1928 to 11.4 per cent in 1929.

112

In June 1929 the Nazi Party took over its first municipality, the Franconian town of Coburg. Here they won 13 out of the 25 seats on the council in the wake of a successful campaign for the removal of the previous council after it had sacked the local Nazi leader, a municipal employee, for making antisemitic speeches. The victory reflected in part the huge effort the Party put into the elections, with top speakers like Hermann Goring and even Hitler himself appearing at the hustings. But it also demonstrated that there was electoral capital to be won in local politics, where the Party now became much more active than before.

113

And in the autumn of 1929 there was a further electoral bonus for the Party, in the shape of the campaign against the Young Plan (which involved the reduction and rescheduling of reparations payments, but not their abolition) organized by the Nationalists. Their leader, Alfred Hugenberg, enlisted the support of the Nazis and other ultra-right groups in his efforts to win acceptance for a referendum on his proposal for a law to reject the plan and prosecute any government ministers who signed it. Not only did the Nazis gain publicity from this campaign, they also won a degree of respectability on the mainstream right through the presence of Hitler on the organizing committee, along with such Pan-German stalwarts as Heinrich Class and the Steel Helmet leaders Franz Seldte and Theodor Duesterberg. The referendum itself was a failure, with only 5.8 million votes in favour. But the campaign had revealed to many supporters of the Nationalists how much more dynamic the brown-shirted and jackbooted Nazis were than the frock-coated and top-hatted leaders of their own party.

114

Meanwhile, Hitler was soon whipping up popular enthusiasm again, his charisma now reinforced by the leadership cult that had grown up around him within the Party. An important symbolic expression of this was the use of the ‘German greeting’, ‘Hail Hitler!’ with outstretched right arm, whether or not Hitler was present. Made compulsory in the movement in 1926, it was also used increasingly as a sign-off in correspondence. These customs reinforced the movement’s total dependence on Hitler, and were enthusiastically propagated by the second tier of leaders who had now gathered around him, whether, as with Gregor Strasser, for tactical reasons, to cement the Party’s unity, or, as with Rudolf Hess, out of blind, religious faith in the person of the ‘Leader’, as he was now generally known.

115

At the Party rally, held in Nuremberg in August 1929, and the first such meeting since 1927, the Party’s new-found confidence and coherence was demonstrated in a huge propaganda display, attended, so the police thought, by as many as 40,000 people, all united in their adulation for the Leader.

116

By this time the Nazi Party had become a formidable organization, its regional, district and local levels staffed with loyal and energetic functionaries, many of them well educated and administratively competent, and its propaganda appeal channelled through a network of specialist institutions directed at particular constituents of the electorate.

117

Despite Hitler’s repeated insistence that politics was a matter for men, there was now a Nazi women’s organization, the self-styled German Women’s Order, founded by Elsbeth Zander in 1923 and incorporated as a Nazi Party affiliate in 1928. Its membership was estimated by the police to have reached 4,000 by the end of the decade, nearly half the Nazi Party’s total female membership of 7,625. The German Women’s Order was one of those paradoxical women’s organizations that campaigned actively in public for the removal of women from public life: militantly anti-socialist, anti-feminist and antisemitic. Its practical activities included running soup kitchens for brownshirts, helping with propaganda campaigns, hiding weapons and equipment for the Nazi paramilitaries when they were being sought by the police, and providing nursing services for wounded activists through its sub-organization the ‘Red Swastika’, a Nazi version of the Red Cross.

118