The Coming of the Third Reich (49 page)

Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

The new situation after the Nazis’ electoral breakthrough not only sharply escalated the level of violence on the streets, it also radically altered the nature of proceedings in the Reichstag. Rowdy and chaotic enough even before September 1930, it now became virtually unmanageable, as 107 brown-shirted and uniformed Nazi deputies joined 77 disciplined and well-organized Communists in raising incessant points of order, chanting, shouting, interrupting and demonstrating their total contempt for the legislature at every juncture. Power drained from the Reichstag with frightening rapidity, as almost every session ended in uproar and the idea of calling it together for a meeting came to seem ever more pointless. From September 1930 only negative majorities were possible in the Reichstag. In February 1931, recognizing the impossibility of carrying on, it adjourned itself for six months as the parties of the extreme right and left demonstratively walked out of a debate after amendments to the parliamentary rule book made it more difficult for them to obstruct business. The deputies did not return until October.

107

The Reichstag sat on average a hundred days a year from 1920 to 1930. It was in session for fifty days between October 1930 and March 1931; after that, it only met on twenty-four further days up to the elections of July 1932. From July 1932 to February 1933 it convened for a mere three days in six months.

108

By 1931, therefore, decisions were no longer really being made by the Reichstag. Political power had moved elsewhere - to the circle around Hindenburg, with whom the right to sign decrees and the right to appoint governments lay, and to the streets, where violence continued to escalate, and where growing poverty, misery and disorder confronted the state with an increasingly urgent need for action. Both these processes greatly enhanced the influence of the army. Only in such circumstances could someone like its most important political representative, General Kurt von Schleicher, become one of the key players in the drama that followed. Ambitious, quick-witted, talkative and rather too fond of political intrigue for his own good, Schleicher was a relatively unknown figure before he suddenly shot to prominence in 1929, when a new office was created for him, the ‘Ministerial Office’, which had the function of representing the armed forces in their relations with the government. A close collaborator of Groener for many years, and a disciple of the leading general of the early 1920s, Hans von Seeckt, Schleicher had forged many political connections through running a variety of offices at the interface of military and political affairs, most recently the army section of the Defence Ministry. The dissident Russian Communist Leon Trotsky described him as ‘a question mark with the epaulettes of a general’; a contemporary journalist saw him as a ‘sphinx in uniform’. But for the most part Schleicher’s aims and beliefs were clear enough: like many German conservatives in 1932, he thought that an authoritarian regime could be given legitimacy by harnessing and taming the popular might of the National Socialists. In this way, the German army, for which Schleicher spoke, and with which he continued to have very close contacts, would get what it wanted in the way of rearmament.

109

Brüning’s government ran into increasing difficulties with Schleicher and the circle around President Hindenburg after the elections of September 1930. With the Communists and the Nazis baying for his blood, the Nationalists trying to oust him, and far-right fringe groups divided over whether to support him or not, Brüning had no option but to rely on the Social Democrats. For their part, the leaders of what was still the largest party in the Reichstag were sufficiently shocked by the election results to promise that they would not repeat their earlier rejection of the budget. Brüning’s dependence on the tacit toleration of his policies by the Social Democrats won him no credit at all among the circle around Hindenburg, led by his son Oskar and his State Secretary Meissner, who regarded this as a shameful concession to the left.

110

The Chancellor’s main priorities now lay in the field of foreign policy, where he made some headway in securing the end of reparations - abrogated by the Hoover Moratorium on 20 June 1931 and effectively ended by the Lausanne Conference, for which Brüning had laid much of the groundwork, in July 1932. And although he failed to achieve the creation of an Austro-German Customs Union, he did conduct successful negotiations in Geneva for the international recognition of German equality in questions of disarmament, a principle eventually conceded in December 1932. However, none of this did anything to strengthen the Chancellor’s political position. After many months in office, he had still failed to win over the Nationalists and was still dependent on the Social Democrats. This meant that any plans either Brüning himself or the circle around Hindenburg might have had to amend the constitution decisively in a more authoritarian direction were effectively stymied, since this was the one thing to which the Social Democrats would never give their assent. To men such as Schleicher, shifting the government’s mass support from the Social Democrats to the Nazis seemed increasingly to be the better option.

111

III

As 1932 dawned, the venerable Paul von Hindenburg’s seven-year term of office as President was coming to an end. In view of his advanced years - he was 84 - Hindenburg was reluctant to stand again, but he had let it be known that he would be willing to continue in office if his tenure could simply be prolonged without an election. Negotiations over automatically renewing Hindenburg’s Presidency foundered on the refusal of the Nazis to vote in the Reichstag for the necessary constitutional change without the simultaneous dismissal of Brüning and the calling of a fresh general election in which, of course, they expected to make further huge gains.

112

Hindenburg was thus forced to undergo the indignity of presenting himself to the electorate once more. But this time things were very different from the first time round, in 1925. Of course, Thälmann stood again for the Communists. But in the meantime Hindenburg had been far outflanked on the right; indeed, the entire political spectrum had shifted rightwards since the Nazi electoral landslide of September 1930. Once the election was announced, Hitler could hardly avoid standing as a candidate himself. Several weeks passed while he dithered, however, fearful of the consequences of running against such a nationalist icon as the hero of Tannenberg. Moreover, technically he was not even allowed to stand since he had not yet acquired German citizenship. Hurried arrangements were made for him to be appointed as a civil servant in Braunschweig, a measure that automatically gave him the status of a German citizen, confirmed when he took the oath of allegiance (to the Weimar constitution, as all civil servants had to) on 26 February 1932.

113

His candidacy transformed the election into a contest between right and left in which Hitler was unarguably the candidate for the right, which made Hindenburg, extraordinarily, incredibly, the candidate for the left.

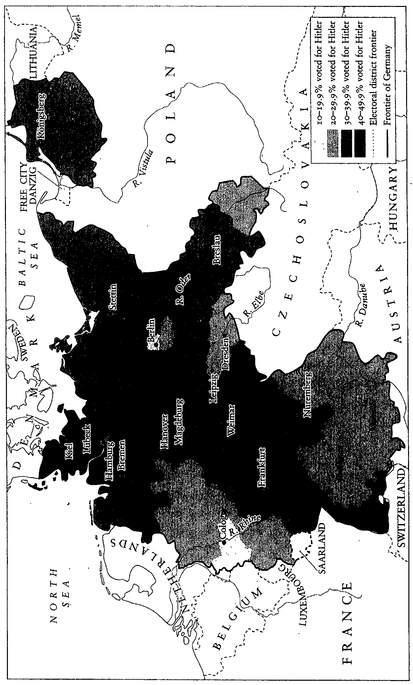

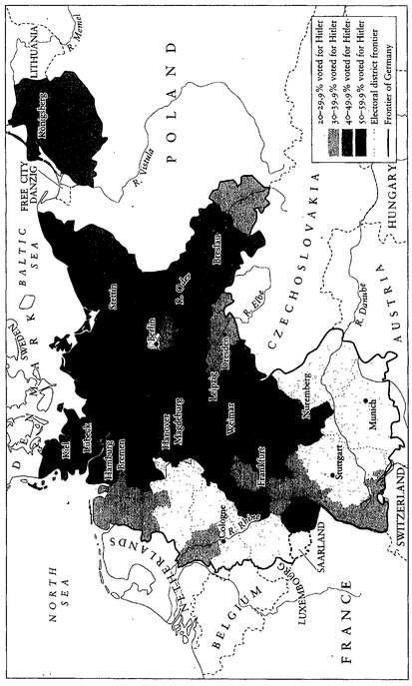

Map 12. The President Election of 1932 First Round.

The Centre and the liberals backed Hindenburg, but what was particularly astonishing was the degree of support he received from the Social Democrats. This was not merely because the party considered him the only man who could stop Hitler - a point the party’s propaganda made repeatedly throughout the election campaign - but for positive reasons as well. The party leaders were desperate to re-elect Hindenburg because they thought that he would keep Brüning in office as the last chance of a return to democratic normality.

114

Hindenburg, declared the Social Democratic Prussian Minister-President Otto Braun, was the ‘embodiment of calm and constancy, of manly loyalty and devotion to duty for the whole people’, a ‘man on whose work one can build, as a man of pure desire and serene judgment’.

115

Already at this time, as these astonishing sentences showed, the Social Democrats were beginning to lose touch with political reality. Eighteen months of tolerating Brüning’s cuts in the name of preventing something worse had relegated them to the sidelines of politics and robbed them of the power of decision. Despite disillusionment and defections amongst their members, their disciplined party machine duly delivered more than 8 million votes to the man who was to dismantle the Republic from above, in an effort to keep in office a Chancellor whom Hindenburg actually disliked and distrusted, and whose policies had been lowering the living standards and destroying the jobs of the very people the Social Democrats represented.

116

Map 13. The President Election of 1932 . Second Round

The threat of a Nazi victory was real enough. The Goebbels propaganda machine found a way of combating Hindenburg without insulting him: he had done great service to the nation, but now was the time for him finally to step aside in favour of a younger man, otherwise the drift into economic chaos and political anarchy would continue. The Nazis unleashed a massive campaign of rallies, marches, parades and meetings, backed by posters, flysheets and ceaseless exhortations in the press. But it was not enough. In the first ballot, Hitler only managed to win 30 per cent of the vote. Yet despite the efforts of the Social Democrats and the electoral strength of the Centre Party, Hindenburg did not quite manage to obtain the overall majority required. He gained only 49.6 per cent of the vote, tantalizingly short of what he needed. On the left, Thälmann offered another alternative. On the right, Hindenburg had been outflanked not only by Hitler but also by Theodor Duesterberg, the candidate put up by the Steel Helmets, who received 6.8 per cent of the vote in the first ballot, which would have been more than enough to have pushed Hindenburg over the winning margin.

117

For the run-off, between Hitler, Hindenburg and Thälmann, the Nazis pulled out all the stops. Hitler rented an aeroplane and flew across Germany from town to town, delivering 46 speeches the length and breadth of the land. The effect of this unprecedented move, billed as Hitler’s ‘flight over Germany’, was electrifying. The effort paid off. Thälmann was reduced to a marginal 10 per cent, but Hitler boosted his vote massively to 37 per cent with over 13 million votes cast in his favour. Hindenburg, with the combined might of all the major parties behind him apart from the Communists and the Nazis, only managed to increase his support to 53 per cent. Of course, despite the hiccup of the first ballot, his re-election had been foreseeable from the start. What really mattered was the triumphant forward march of the Nazis. Hitler had not been elected, but his party had won more votes than ever before. It was beginning to look unstoppable.

118

In 1932, better organized and better financed than in 1930, the Nazi Party had run an American-style Presidential campaign focusing on the person of Hitler as the representative of the whole of Germany. It had concentrated its efforts not so much on winning over the workers, where its campaign of 1930 had largely failed, but in garnering the middle-class votes that had previously gone to the splinter-parties and the parties of the liberal and conservative Protestant electorate. Eighteen months of worsening unemployment and economic crisis had further radicalized these voters in their disillusion with the Weimar Republic, over which, after all, Hindenburg had been presiding for the past seven years. Goebbels’s propaganda apparatus targeted specific groups of voters with greater precision than ever before, above all women. In the Protestant countryside, rural discontent had deepened to the point where Hitler actually defeated Hindenburg in the second round in Pomerania, Schleswig-Holstein and Eastern Hanover.

119

And the Nazi movement’s new status as Germany’s most popular political party was underlined by further victories in the state elections held later in the spring - 36.3 per cent in Prussia, 32.5 per cent in Bavaria, 31.2 per cent in Hamburg, 26.4 per cent in Württemberg, and, above all, 40.9 per cent in Saxony-Anhalt, a result that gave them the right to form a state government. Once more, Hitler had taken to the air, delivering 25 speeches in quick succession. Once more, the Nazi propaganda machine had proved its efficiency and its dynamism.