Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

The Coming of the Third Reich (58 page)

We were prepared; we knew the intentions of our enemies. I had put together a small ‘mobite squad’ of my storm from the most daring of the daring. We lay in wait night after night. Who was going to strike the first blow? And then it came. The beacon in Berlin, signs of fire all over the country. Finally the relief of the order: ‘Go to it!’ And we went to it! It was not just about the purely human ‘you or me’, ‘you or us’, it was about wiping the lecherous grin off the hideous, murderous faces of the Bolsheviks for all time, and protecting Germany from the bloody terror of unrestrained hordes.

69

All over Germany, however, it was now the brownshirts who visited ‘the bloody terror of unrestrained hordes’ upon their enemies. Their violence was the expression of long-nurtured hatred, their actions directed against individual ‘Marxists’ and Communists often known to them personally. There was no coordinated plan, no further ambition on their part than the wreaking of terrible physical aggression on men and women they feared and hated.

70

The brownshirts and the police might have been prepared; but in crucial respects their Communist opponents were not. The Communist Party leadership was taken unawares by the events of 27-8 February. It thought that it would be entering another period of relatively mild repression such as it had successfully survived in 1923 and 1924. This time, however, things were very different. The police were backed by the full ferocity of the brownshirts. The party leader and former candidate for the Reich Presidency Ernst Thälmann and his aides were arrested on 3 March in his secret headquarters in Berlin-Charlottenburg. Ernst Torgler, the party’s floor leader in the Reichstag, gave himself up to the police on 28 February in order to refute the government’s accusation that he and the party leadership had ordered the burning of the Reichstag building. Of the leading party figures, Wilhelm Pieck left Germany in the spring, Walter Ulbricht, head of the party in Berlin, in the autumn. Strenuous efforts were made to smuggle out other politburo members, but many of them were arrested before they could escape. All over the country, Communist Party organizations were smashed, offices occupied, activists taken into custody. Often the stormtroopers carried off any funds they could lay their hands on, and looted the homes of Communist Party members for cash and valuables while the police looked on. Soon the wave of arrests swelled to many times the number originally envisaged. Ten thousand Communists had been put into custody by 15 March. Official records indicated that 8,000 Communists were arrested in the Rhine and Ruhr district in March and April 1933 alone. Party functionaries were obliged to admit that they had been compelled to carry out a ‘retreat’, but insisted that it was an ‘orderly retreat’. In fact, as Pieck conceded, within a few months most of the local functionaries were no longer active, and many rank-and-file members had been terrorized into silence.

71

Hitler evidently feared that there would be a violent reaction if he obtained a decree outlawing the Communist Party altogether. He preferred instead to treat individual Communists as criminals who had planned illegal acts and were now going to pay the consequences. That way, the majority of Germans might be won over to tolerate or even support the wave of arrests that followed the Reichstag fire and would not fear that this would be followed by the outlawing of other political parties. It was for this reason that the Communist Party was able to contest the elections of 5 March 1933, despite the fact that a large number of its candidates were under arrest or had fled the country, and there was never any chance that the 81 deputies who were elected would be able to take up their seats; indeed, they were arrested as soon as the police were able to locate them. By allowing the party to put up candidates in the election, Hitler and his fellow ministers also hoped to weaken the Social Democrats. If Communist candidates had not been allowed to stand, then many of the electors who would have voted for them might have cast their ballot for the Social Democrats instead. As it was, the Social Democrats were deprived of this potential source of support. Even towards the end of March the cabinet still felt unable to issue a formal prohibition of the Communist Party. Nevertheless, as well as being murdered, beaten up or thrown into makeshift torture centres and prisons set up by the brownshirts, Communist functionaries, particularly if they had been arrested by the police, were prosecuted in large numbers through the regular criminal courts.

Mere membership of the party was not in itself illegal. But police officials, state prosecutors and judges were overwhelmingly conservative men. They had long regarded the Communist Party as a dangerous, treasonable and revolutionary organization, particularly in the light of the events of the early Weimar years, from the Spartacist uprising in Berlin to the ‘red terror’ and the hostage shootings in Munich. Their view had been amply confirmed by the street violence of the Red Front-Fighters’ League and now, many thought, by the Reichstag fire. The Communists had burned down the Reichstag, so all Communists must be guilty of treason. Even more tortuous reasoning was sometimes employed. In some cases, for instance, the courts argued that since the Communist Party was no longer able to pursue its policies of changing the German constitution by parliamentary means, it must be trying to change it by force, which was now a treasonable offence, so anyone who belonged to it must be doing the same. Increasingly, therefore, the courts treated membership of the party after 3o January 1933, occasionally even before that, as a treasonable activity. In all but name, the Communist Party was effectively outlawed from 28 February 1933, and completely banned from 6 March onwards, the day after the election.

72

Having driven the Communists from the streets in a matter of days after 28 February, Hitler’s stormtroopers now ruled the cities, parading their newly won supremacy in the most obvious and intimidatory manner. As the Prussian political police chief Rudolf Diels later reported, the SA, in contrast to the Party, was prepared to seize power.

It did not need a unified leadership; the ‘Group Staff’ set an example but gave no orders. The SA storm-squads, however, had firm plans for operations in the Communist quarters of the city. In those March days every SA man was ‘on the heels of the enemy’, each knew what he had to do. The storm-squads cleaned up the districts. They knew not only where their enemies lived, they had also long ago discovered their hideouts and meeting places ... Not only the Communists, but anybody who had ever spoken out against Hitler’s movement, was in danger.

73

Brownshirt squads stole cars and pick-up trucks from Jews, Social Democrats and trade unions, or were presented with them by nervous businessmen hoping for protection. They roared along Berlin’s main streets, weapons on show and banners flying, advertising to everyone who was the boss now. Similar scenes could be observed in towns and cities across the land. Hitler, Goebbels, Goring and the other Nazi leaders had no direct control over these events. But they had both unleashed them, by enrolling the Nazi stormtroopers along with the SS and Steel Helmets as auxiliary police on 22 February, and given them general, more than implicit approval, by the constant, repeated violence of their rhetorical attacks on ‘Marxists’ of all kinds.

Once more, a dialectical process was at work, forged in the days when the Nazis often faced police hostility and criminal prosecution for their violence: the leadership announced in extreme but unspecific terms that action was to be taken, and the lower echelons of the Party and its paramilitary organizations translated this in their own terms into specific, violent action. As a Nazi Party internal document later noted, action of this kind, by a nod-and-a-wink, had become already the custom in the 1920s. At this time, the rank-and-file had become used to reading into their leaders’ orders rather more than the actual words that their leaders uttered. ‘In the interest of the Party,’ the document continued, ‘it is also in many cases the custom of the person issuing the command - precisely in cases of illegal political demonstrations - not to say everything and just to hint at what he wants to achieve with the order.’

74

The difference now was that the leadership had the resources of the state at its disposal. It was able by and large to convince civil servants, police, prison administrators and legal officials - conservative nationalists almost to a man - that the forcible suppression of the labour movement was justified. So it persuaded them that they should not merely stand aside when the stormtroopers moved in, but should actively help them in their work of destruction. This pattern of decision-making and its implementation was to be repeated on many occasions subsequently, most notably in the Nazis’ policy towards the Jews.

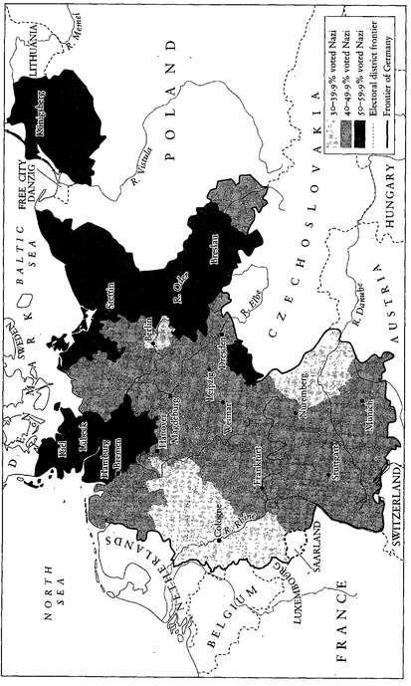

Map 17. The Nazis in the Reichstag of March 1933

III

The Nazis’ campaign for the Reichstag elections of 5 March 1933 achieved saturation coverage all over Germany.

75

Now the resources of big business and the state were thrown behind their efforts, and, as a result, the whole nature of the election was transformed. In the small north German town of Northeim, for instance, as in virtually every other locality, the elections were held in an atmosphere of palpable terror. The local police were positioned by the railway station, bridges and other key installations, advertising the regime’s claim that such places were vulnerable to terrorist attacks by the Communists. The local stormtroopers were authorized to carry loaded firearms on 28 February and enrolled as auxiliary police on 1 March, whereupon they ostentatiously began to mount patrols in the streets, and raided the houses of local Social Democrats and Communists, accusing them both of preparing a bloodbath of honest citizens. The Nazi newspaper reported that a worker had been arrested for distributing a Social Democratic election leaflet; such activities on behalf of the Social Democrats and the Communists were forbidden, it announced. Having silenced the main opposition, the Nazis set up radio loudspeakers in the Market Square and on the main street, and every evening from 1 to 4 March Hitler’s speeches were amplified across the whole town centre. On election eve, six hundred stormtroopers, SS men, Steel Helmets and Hitler Youth held a torchlight parade through the town, ending in the city park to listen to loudspeakers booming out a radio relay of a speech by Hitler that was simultaneously blared out to the public in four other major public locations in the town centre. Black-white-red flags and swastika banners bedecked the main streets, and were displayed in shops and stores. Opposition propaganda was nowhere to be seen. On election day - a Sunday - the brownshirts and SS patrolled and marched menacingly through the streets, while the Party and the Steel Helmets organized motor transport to get people to the polling stations. The same combination of terror, repression and propaganda was mobilized in every other community, large and small, across the land.

76

When the results of the Reichstag elections came in, it seemed that these tactics had paid off. The coalition parties, Nazis and Nationalists, won 51.9 per cent of the vote. ‘Unbelievable figures,’ wrote Goebbels triumphantly in his private diary for 5 March 1933: ‘it’s like we’re on a high.’

77

Some constituencies in central Franconia saw the Nazi vote at over 80 per cent, and in a few districts in Schleswig-Holstein the Party gathered nearly all the votes cast. Yet the jubilation of the Party bosses was ill-placed. Despite massive violence and intimidation, the Nazis themselves had still managed to secure only 43.9 per cent of the vote. The Communists, unable to campaign, with their candidates in hiding or under arrest, still managed 12.3 per cent, a smaller drop from their previous vote than might have been expected, while the Social Democrats, also suffering from widespread intimidation and interference with their campaigning, did only marginally worse than in November 1932, with 18.3 per cent. The Centre Party more or less held its own at 11.2 per cent, despite losses to the Nazis in some parts of the south, and the other, now minor, parties repeated their performance of the previous November with only slight variations.

78

Seventeen million people voted Nazi, and another 3 million Nationalist. But the electorate numbered almost 45 million. Nearly 5 million Communist votes, over 7 million Social Democrats, and a Centre Party vote of 5.5 million, testified to the complete failure of the Nazis, even under conditions of semi-dictatorship, to win over a majority of the electorate.

79

Indeed, at no time since their rise to electoral prominence at the end of the 1920s had they managed to win an absolute majority on their own at the Reich level or within any of the federated states. Moreover, the majority they obtained together with their coalition partners the Nationalists in March 1933 fell far short of the two-thirds needed to secure an amendment of the constitution in the Reichstag. What the elections did make clear, however, was that nearly two-thirds of the voters had lent their support to parties - the Nazis, the Nationalists, and the Communists - who were open enemies of Weimar democracy. Many more had voted for parties, principally the Centre Party and its southern associate the Bavarian People’s Party, whose allegiance to the Republic had all but vanished and whose power over their constituencies was now being seriously eroded. In 1919, three-quarters of the voters had backed the Weimar coalition parties. It had taken only fourteen short years for this situation to be effectively reversed.

80