The Complete Guide to English Spelling Rules (51 page)

Read The Complete Guide to English Spelling Rules Online

Authors: John J Fulford

Note that there is a great deal of confusion, even among the experts, over the exact meaning of many of these terms. Some see

digraph

and

diphthong

as the same thing. Some use

homonym

to cover both

homographs

and

homophones.

Others just lump all the terms together and call them

phonemes

and

graphemes,

words that sound alike and words that are written alike.

O

ne of the many marvels of the English language is the way in which it borrows words from any and every source and, if a word is not readily available, we manufacture a new one by compounding or contraction. Or we just make up a new word.

Acronyms are a special group of manufactured words that go through a process of assimilation that is often quite rapid, though sometimes they are never fully assimilated. The radar set did not even exist before 1940, yet today

radar

is almost a household word. The word is made up from the initial letters of

Radio Detection And Receiving.

During World War II, servicemen quickly called it RADAR, and it even more speedily lost its uppercase spelling and became

radar.

Ten years later, the

Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus

was invented, and, almost overnight, we had the highly popular

scuba

outfit. These are just two of the better known acronyms. The advent of the personal computer has produced a steady stream of new and exotic words, many of which started life as acronyms and rapidly became regular words.

The creation and assimilation of acronyms has created its own set of spelling rules.

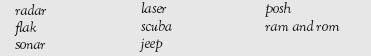

Spelling rule: Brand new acronyms consist of capital letters with periods between each letter. Intermediate stage acronyms are still in capital letters, but they have lost the periods. Mature acronyms have split into two groups:

(1) Names or proper nouns, spelled in capital letters with no periods:

(2) Regular words with neither capitals nor periods:

Note that not all abbreviations become acronyms. For example, the UN, MI5, the FBI, and IRA are always pronounced as separate letters.

A

good dictionary is indispensable. English spelling is so complex that nobody can claim that they have a perfect grasp and that they do not need a dictionary. But there is a huge variety of dictionaries. They come in all sizes and cover all subjects. There are scientific dictionaries and medical dictionaries, and there are dictionaries of almost every known language. There are dictionaries of proverbs, of quotes, of slang, of strange words, and of obsolete words. One might wonder if there is a dictionary for every subject under the sun.

Many publishers, both small and large, have produced a dictionary and many of them call their product a “Webster’s dictionary.” Because the name is not a protected name, as the name Merriam-Webster is, there is nothing to prevent any publisher from using it, and many do. Since no modern dictionary is even remotely similar to Noah Webster’s original masterpiece, the name has no real meaning today.

The accuracy of a dictionary can not be taken for granted. A detailed study of any three or four dictionaries would very quickly produce scores of disagreements and even some contradictions regarding the correct spelling of some words. Unfortunately, when there is a difference in spelling, most dictionaries play it safe and offer the reader a choice of what is available with little, if any, explanation.

Modern publishers do not tread the path first blazed by Noah Webster. For the most part, they are merely compilers of word lists, content to stick to the status quo. They see themselves as recorders of what exists today with no duty to give more than the necessary facts and, perhaps, the etymology of the word. They sell their product by trumpeting the number of words they have listed and increase the size of the book by adding material that better belongs in an atlas or encyclopedia.

Few, if any, dictionaries attempt to influence spelling by coming down firmly in favor of a particular spelling that logically follows the spelling rules as against a spelling that is an aberration. Also, most dictionaries are hesitant, almost

reluctant, to accept new spellings despite the fact that English spelling is constantly changing.

Noah Webster would be most annoyed. He saw his dictionary as a teaching tool to be used as a powerful influence on the language. He believed that a dictionary should lead, not follow, and that it should do so energetically. He forced Americans, and the world, to re-evaluate English spelling in order to make it more logical. If Webster had been content to simply list all the words as they then existed—complete with illogical spellings—the American version of the English language would not be what it is today and Webster would have vanished into obscurity like the dictionary compilers who preceded him.

R

eaders who are learning English may wonder if they should try to acquire an American accent or a British accent. The answer is quite simple. Neither.

Today in England alone, there are over twenty regional accents that most Englishmen recognize and many more local accents that are not so easy to define. Educated, middle-class Englishmen attempt to speak standard, or BBC, English, but there is also the problem of class, a very important element in English life. Members of the upper class define themselves by speaking in an exaggerated manner, while the lower classes continue to use the regional accents. The end result is that the national language is badly fragmented and no single region may be said to speak in a “typically English” accent.

The pattern is similar in North America, where there are numerous regional accents that everybody recognizes and many less easily definable accents. Fortunately, North Americans do not have an upper-class accent to complicate matters. Most educated, upper- and middle-class North Americans speak what is called “middle American,” while the lower classes tend to emphasize their regional accents. But there is no “typically American” accent.

The English have a saying, “If you hear somebody speaking perfectly correct English, they’re probably not English.” Obviously, the student will not attempt to copy any of the regional accents, but one pitfall that should be avoided is the affectation among the middle and upper class of turning many of the

a

sounds into

ah

sounds.

The spelling rule is clear. “Unless it is modified by a silent

e

or other modifying vowels, the

a

is almost always a short vowel, especially if it is followed by a doubled consonant. The

a

only sounds like

ah

when followed by the letter

r

.” For example:

bar, car, far, jar, star,

etc. These have the

ah

sound, but

class, pass, ass, grass, glass,

etc. do not.

This affectation is quite popular, and the student will hear a great number of words that have a short

a

pronounced as if the

a

were a long vowel. For example:

passport, banana, can’t, example, plant, fast, glance, dance, chance.

It becomes

ludicrous when even the names of foreign countries are mispronounced and

Iran, Pakistan,

and

Afghanistan

become

Irahn, Pahkistahn,

and

Ahfgahnistahn.

The English-speaking population of North America is well over 300 million, while the combined population of all the other English-speaking nations—Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, South Africa, the West Indies—is less then 100 million. North America is also the greatest exporter of movies and TV shows and has the largest number of foreign students studying in its universities, so it is obvious that the North American version of the English language is the dominant version. There are two major pitfalls that the foreign student must avoid.

First, many North Americans have great difficulty pronouncing an internal

t.

Almost daily you will hear

innernet (internet), innernational (international), innerested (interested), budder (butter), bedder (better), badder (batter), liddle (little), waiding (waiting), seddle (settle), gedding (getting), ledder (letter),

and many other poorly pronounced words. The student should carefully pronounce the internal

t

whenever it is supposed to be pronounced.

Second, in a great many parts of North America the sound of the vowel

o

is changed to a.

Hot

becomes

hat, got

becomes

gat,

and

Colorado

becomes

Calarado.

This is often, but not always, a regional accent, and North Americans from New York to Toronto to Los Angeles can be heard mispronouncing the letter

o

in this way. The student should always take care to pronounce this vowel correctly, bearing in mind that if we hope for clear communication, enunciation is as important as pronunciation.

End

J

OHN

F

ULFORD’S

first experience as a teacher was in a lonely, one-room school in northern Canada. Among his students that winter were some French-speaking children and half a dozen Native Americans. He survived the winter, and during his subsequent forty years of teaching he taught every grade from kindergarten to college prep. as well as adult education. He has also taught overseas.

J

OHN

F

ULFORD

Born in Spain of British parents, the author was educated in England and after a stint in the RAF, he worked as the advertising manager and proofreader on a small magazine in London before emigrating to Canada, where he earned his B. Ed. at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. After moving to California, he earned his M.A. at California State University in Long Beach.

Mr Fulford was an avid book worm by the second grade and acquired his love for the English language from his mother, who was an English teacher, and from his father, who was a Fleet Street journalist and editor and a war correspondent during World War II.