The Complete Yes Minister (66 page)

I agreed with him heartily. ‘Yes, absolutely shocking. I wasn’t pleased either.’

‘There’s obviously been a leak,’ he murmured, eyeing me.

‘Terrible. Can’t trust any of my Cabinet colleagues nowadays.’

This wholehearted agreement threw him momentarily off guard, I think. ‘Who are you saying it was?’ he asked.

I lowered my voice and explained that I wouldn’t want to name names, but as for one or two of my Cabinet colleagues . . . well! I left it at that. Looks speak louder than words sometimes.

He didn’t want to leave it there. ‘But what are you suggesting?’

I immediately backtracked. I was enjoying myself hugely. ‘Well,’ I said, ‘it may

not

have been one of them, of course. I did send the paper here to Number Ten – could there be a leak

here

somewhere, do you think?’

not

have been one of them, of course. I did send the paper here to Number Ten – could there be a leak

here

somewhere, do you think?’

Sir M. was not amused. ‘The PM’s office does not leak.’

‘Of course not,’ I said quickly. ‘Perish the thought.’

We all leak of course. That’s what the lobby correspondents are there for. However, we all prefer to call it ‘flying a kite.’

Sir Mark continued. ‘It wasn’t only the fact of the leak that was disturbing. It was the implications of the proposals.’

I agreed that the implications were indeed disturbing, which was why I had written a special paper for the PM. National transport policies are bound to have disturbing implications. He disagreed. He insisted that the Transport Policy will not have such implications.

‘It will,’ I said.

‘It won’t,’ he said. Such is the intellectual cut and thrust to be found at the centre of government.

‘Didn’t you read what it said?’ I asked.

‘What it

said

is not what it will

be

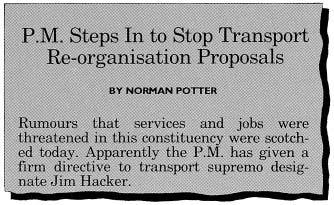

,’ he replied very firmly. ‘I thought perhaps you’d like to see this.’ And he handed me a newspaper, one of the London suburban weeklies.

said

is not what it will

be

,’ he replied very firmly. ‘I thought perhaps you’d like to see this.’ And he handed me a newspaper, one of the London suburban weeklies.

It was the local paper from the PM’s constituency.

This was certainly news to me.

‘I’ve had no directive from the PM,’ I said.

‘You have now.’ What a curious way to get a directive from the PM. ‘I’m afraid this leak, whoever it comes from, is a verbatim report of a confidential minute dictated by the Prime Minister in Ottawa. So it looks as though the national transport policy will need some rethinking, doesn’t it?’

This leak was a skilful counter-move by the PM. I started to explain to Sir Mark that rethinking the policy would be difficult, but he interrupted me unceremoniously.

‘I think the PM’s view is that Ministers are there to do difficult jobs. Assuming that they wish to remain as Ministers.’

Tough talk. I got the message.

I hastened to assure him that if the policy needed rethinking then I would rethink it until it was well and truly rethought.

Before I left I asked him how the leak had got into the paper. The PM’s own local paper. He assured me that he had no idea, but that the PM’s office does not leak.

‘Shocking, though, isn’t it?’ he added. ‘You can’t trust anyone nowadays.’

August 23rd

Another meeting with Humphrey. We appeared to be back to square one.

I was somewhat downcast, as I still appeared to be landed with this ghastly job. To my surprise Humphrey was in good spirits.

‘It’s all going excellently, Minister,’ he explained. ‘We shall now produce the other kind of non-proposal.’

I asked him what he had in mind.

‘The high-cost high-staff kind of proposal. We now suggest a British National Transport Authority, with a full structure of Regional Boards, Area Councils, local offices, liaison committees – the lot. Eighty thousand staff, and a billion pounds a year budget.’

‘The Treasury will have a fit,’ I said.

‘Precisely. And the whole matter will certainly be handed back to the Department of Transport.’

I was entranced. I asked him to do me a paper with full staff and costing details and a specimen annual budget.

He was way ahead of me. He immediately produced the very document from his folder. ‘And there’s a one-page summary on the front,’ he smiled smugly. Well, he was entitled to be smug!

I told him he was wonderful. He told me it was nothing.

I sat back and glanced through the proposal. It was splendid stuff.

‘My goodness,’ I reflected, ‘if the press were to get hold of

this

. . . eh?’

this

. . . eh?’

Humphrey smiled. ‘They’ll soon be setting up another leak enquiry.’

Bernard was immediately anxious. ‘Not really?’

‘Bound to.’

‘But . . . wouldn’t that be embarrassing?’

I was surprised to see that Bernard didn’t know the rules of the leak enquiry game. Leak enquiries are never embarrassing because they never actually happen. Leak enquiries are for setting up, not for actually conducting. Members may be appointed, but they hardly ever meet more than once. They certainly never report.

I asked Bernard, ‘How many leak enquiries can you recall that named the culprit?’

‘In round figures,’ added Humphrey.

Bernard thought for a moment. ‘Well, if you want it in round figures . . .’ He thought again. ‘None.’

The right answer. They

can’t

report. For two reasons:

can’t

report. For two reasons:

If the leak came from a civil servant it’s not

fair

to publish it. The politicians are supposed to take the rap, that’s what they’re there for.

fair

to publish it. The politicians are supposed to take the rap, that’s what they’re there for.

If the leak came from a politician it’s not

safe

to publish it, because he will then promptly disclose all the other leaks he knows of that came from his Cabinet colleagues.

safe

to publish it, because he will then promptly disclose all the other leaks he knows of that came from his Cabinet colleagues.

I explained all this to Bernard.

Then Humphrey chimed in. ‘There’s a third reason. The most important of all. The main reason why it’s too dangerous to publish the results of an enquiry is because most leaks come from Number Ten. The ship of state is the only ship that leaks from the top.’

Humphrey was quite right, of course. Since the problem, more often than not, is a leaky PM – as in this case – it’s not easy to get the evidence and impossible to publish it if you do.

And by a curious coincidence, a journalist arrived to see me this very morning, shortly after our meeting. Humphrey, most considerately, left a spare copy of our latest high-cost proposal lying around on my desk. I’m awfully absent-minded, I’m always leaving bits of paper lying around, forgetting where I put them – the upshot was that after the journalist had left my office I couldn’t find my spare copy anywhere. Extraordinary!

August 25th

It all came to a head today.

Humphrey and I were summoned – together this time – to a meeting at Number Ten. We were ushered into the Cabinet Secretary’s office, where Sir Arnold and Sir Mark sat at the far end of a very long room. I think they were trying to intimidate us. But Humphrey and I are made of sterner stuff.

We greeted them cheerfully, and I sat in one of the armchairs in the conversation area. As a Minister of the Crown they were all my servants (nominally, at least) so they could not insist on a desk-bound interview. At my suggestion they joined me in Sir Arnold’s armchairs. But he opened the batting. ‘Another leak,’ he said. ‘This is extremely serious.’

‘There has indeed been another leak,’ I agreed. ‘I can’t think how it occurred! Our high-cost proposal was all over this morning’s papers.’

Humphrey and I agreed earnestly that this new leak was indeed extremely serious.

‘It is almost approaching a disciplinary level,’ said Sir Arnold.

‘I do agree,’ I said, ‘don’t you, Humphrey?’

He nodded emphatically. ‘Indeed, if only one could find the culprits it would be a most serious matter for them.’

Sir Mark piped up. He said he could help with that. He thought that if he were to use his influence he could achieve a disclosure from

The Times

of how they got hold of our original transport plans.

The Times

of how they got hold of our original transport plans.

I shook Humphrey up a bit by offering to help further.

‘Are you sure, Minister?’ He sounded a warning note.

‘Oh yes,’ I said. ‘In fact I’m confident that I could find out how the press got hold of the leak about the Prime Minister’s opposition to our original plans. Of course, if it transpires that the PM’s own office leaks, then that would be even more serious than a leak in a cabinet minister’s private office, wouldn’t it? The security implications alone . . .’

I let that threat hang in the air, and sat back.

‘Ah,’ said Sir Mark.

There was a pause while everyone thought and rethought their positions. I felt I had the initiative, so I continued: ‘In fact, perhaps we ought to bring in the police or MI5 – after all, the implications of a leak at Number Ten are really very serious indeed.’

Arnold fought back. ‘Nevertheless, our first priority must be to investigate the original leak.’ He tried to insist.

I contradicted him flatly. ‘No. Our first priority must be to track down the leak involving the PM.’

He really couldn’t argue with that. And he didn’t. He just sat in silence and looked at me. So after a moment, having won the Battle of the Leak Enquiries, I turned to the matter of the Transport Policy.

‘At all events,’ I said, summing up the situation, ‘you will appreciate that the public outcry in response to all these leaks makes it very difficult for me to develop a national transport policy within the DAA.’

Sir Humphrey agreed vigorously. ‘The time is unripe. The climate is unpropitious. The atmosphere is unfavourable.’

‘And,’ I nodded, ‘the only two lines of approach are now blocked.’

Again there was a silence. Again Arnold and Mark stared at me. Then they stared at each other. Defeat stared at them both. Finally Sir Arnold resigned himself to the inevitable.

But he tried to put as good a face on it as he could. He raised the oldest idea as if it were the latest inspiration. ‘I wonder,’ he addressed himself to Sir Mark, ‘if it might not be wiser to take the whole matter back to the Department of Transport?’

I seized on the suggestion. ‘Now that, Arnold,’ I said, flattering him fulsomely, ‘is a brilliant idea.’

‘I wish I’d thought of that,’ said Humphrey wistfully.

So we were all agreed.

But Sir Mark was still worried. ‘There remains the question of the leaks,’ he remarked.

‘Indeed there does,’ I agreed. ‘And in my view we should treat this as a matter of utmost gravity. So I have a proposal.’

‘Indeed?’ enquired Sir Arnold.

‘Will you recommend to the PM,’ I said, in my most judicial voice, ‘that we set up an immediate leak enquiry?’

Sir Arnold, Sir Mark and Sir Humphrey responded in grateful unison. ‘Yes Minister,’ replied the three knights.

1

‘Beware of Greeks bearing gifts’ is the usual rough translation.

‘Beware of Greeks bearing gifts’ is the usual rough translation.

2

London School of Economics.

London School of Economics.

3

A hole in the head.

A hole in the head.

4

In conversation with the Editors.

In conversation with the Editors.

5

Department of Education and Science.

Department of Education and Science.

6

Originally said by Frederick the Great, King Frederick II of Prussia.

Originally said by Frederick the Great, King Frederick II of Prussia.

19

The Whisky Priest

September 4th

A most significant and upsetting event has just taken place. It is Sunday night. Annie and I are in our London flat, having returned early from the constituency.

I had a mysterious phone call as I walked in through the door. I didn’t know who it was from. All the man said was that he was an army officer and that he had something to tell me that he wouldn’t divulge on the phone.

We arranged an appointment for late this evening. Annie read the Sunday papers and I read

The Wilderness Years

, one of my favourite books.

The Wilderness Years

, one of my favourite books.

The man arrived very late for our appointment. I began to think that something had happened to him. By the time he’d arrived my fantasies were working overtime – perhaps because of

The Wilderness Years

.

The Wilderness Years

.

‘Remember Churchill,’ I said to Annie. ‘During all his wilderness years he got all his information about our military inadequacy and Hitler’s war machine from army officers. So all the time he was in the wilderness he leaked stories to the papers and embarrassed the government. That’s what I could do.’

I realised, as I spoke, that I’d chosen inappropriate words to express my feelings. I felt a little ridiculous as Annie said, ‘But you’re in the government.’ Surely she could see what I

meant

!

meant

!

Anyway, the man finally arrived. He introduced himself as Major Saunders. He was about forty years old, and wore the

de rigueur

slightly shabby baggy blue pinstripe suit. Like all these chaps he looked like an overgrown prep school pupil.

de rigueur

slightly shabby baggy blue pinstripe suit. Like all these chaps he looked like an overgrown prep school pupil.

He was not a frightfully good conversationalist to start with. Or perhaps he was just rather overawed to meet a statesman such as myself.

I introduced him to Annie and offered him a drink.

Other books

Return To Snowy Creek by Julie Pollitt

Love Finds Lord Davingdale by Anne Gallagher

Taken by You by Mason, Connie

The Cruiserweight by L. Anne Carrington

American Childhood by Annie Dillard

Lost Angel (The List #1) by N K Love

The Blinded Man by Arne Dahl

Driftwood by Mandy Magro

Los persas by Esquilo

Valeria’s Cross by Kathi Macias & Susan Wales