The Complete Yes Minister (73 page)

[

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

Isn’t it remarkable that this immortal prose should be described as an ‘explanatory note’?

I finished reading it and looked at Bernard.

‘I think that’s quite clear, isn’t it?’ he said.

‘Do I have to bother with all this piddling gobbledegook?’ I replied.

He was slightly put out. ‘Oh, I’m sorry, Minister. I thought that this would be an opportune moment for you to ensure that, as a result of your Ministerial efforts, local councillors would be getting more money for attending council meetings.’

I suddenly realised what he was driving at. I glanced back at Bernard’s summary. There it was, in black and white

and

plain English: ‘Amounts of attendance and financial loss allowances payable to members of local authorities.’ So

that’s

what it all means!

and

plain English: ‘Amounts of attendance and financial loss allowances payable to members of local authorities.’ So

that’s

what it all means!

He had done excellently. This is indeed an opportune moment to display some open-handed generosity towards members of local authorities.

He asked if he could make one further suggestion. ‘Minister, I happen to know that Sir Humphrey and Sir Ian Whitworth have been having discussions on this matter.’

‘Ian Whitworth?’

Bernard nodded. ‘The Corn Exchange is a listed building. So it’s one of his planning inspectors who will be conducting the inquiry. Sir Humphrey and Sir Ian will be laying down some “informal” guidelines for him.’

I was suspicious. Informal guidelines? What did this mean?

Bernard explained carefully. ‘Guidelines are perfectly proper. Everyone has guidelines for their work.’

It didn’t sound perfectly proper to me. ‘I thought planning inspectors were impartial,’ I said.

Bernard chuckled. ‘Oh

really

Minister! So they are! Railway trains are impartial too. But if you lay down the lines for them, that’s the way they go.’

really

Minister! So they are! Railway trains are impartial too. But if you lay down the lines for them, that’s the way they go.’

‘But that’s not

fair

!’ I cried, regressing forty years.

fair

!’ I cried, regressing forty years.

‘It’s politics, Minister.’

‘But Humphrey’s not supposed to be in politics, he’s supposed to be a civil servant. I’m supposed to be the one in politics.’

Then the whole import of what I’d blurted out came home to me. Bernard was nodding wisely. Clearly he was ready and willing to explain what political moves I had to make. I asked him how Humphrey and Ian would be applying pressure to the planning inspector.

‘Planning inspectors have their own independent hierarchy. The only way they are vulnerable is to find one who is anxious for promotion.’

‘Can a Minister interfere?’

‘Ministers are our Lords and Masters.’

So that was the answer. Giles Freeman, the Parly Sec. at the Department of the Environment, is an old friend of mine. I resolved to explain the situation to Giles and get him to intervene. He could, for instance, arrange to give us a planning inspector who doesn’t care about promotion because he’s nearing retirement. Such a man might even give his verdict in the interests of the community.

All I said to Bernard was: ‘Get me Giles Freeman on the phone.’

And to my astonishment he replied: ‘His Private Secretary says he could meet you in the lobby after the vote this evening.’

I must say I was really impressed. I asked Bernard if he ever thought of going into politics. He shook his head.

‘Why not?’

‘Well, Minister, I once looked up politics in the

Thesaurus

.’

Thesaurus

.’

‘What does it say?’

‘“Manipulation, intrigue, wire-pulling, evasion, rabble-rousing, graft . . .” I don’t think I have the necessary qualities.’

I told him not to underestimate himself.

[

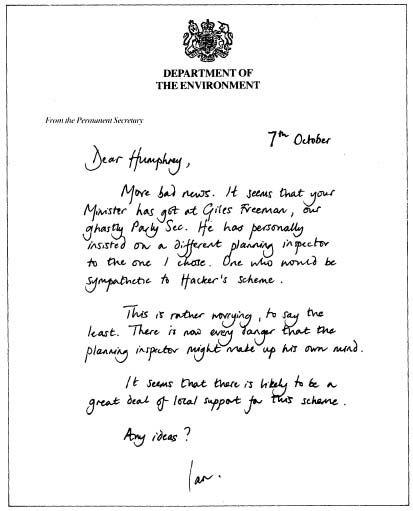

Three days later Sir Humphrey Appleby received another letter from Sir Ian Whitworth – Ed

.]

Three days later Sir Humphrey Appleby received another letter from Sir Ian Whitworth – Ed

.]

[

We can find no written reply to this cry for help. But the following Monday Sir Humphrey and Sir Ian had lunch with Sir Arnold Robinson, the Cabinet Secretary. This account appears in Sir Humphrey’s private diary, and was apparently written in a mood of great triumph – Ed

.]

We can find no written reply to this cry for help. But the following Monday Sir Humphrey and Sir Ian had lunch with Sir Arnold Robinson, the Cabinet Secretary. This account appears in Sir Humphrey’s private diary, and was apparently written in a mood of great triumph – Ed

.]

At lunch with Arnold and Ian today I brought off a great coup.

Ian wanted to discuss our planning problem. I had invited Arnold because I knew that he held the key to it.

Having briefed him on the story so far, I changed the subject to discuss the Departmental reorganisation which is due next week. I suggested that Arnold makes Hacker the Cabinet Minister responsible for the Arts.

Arnold objected to that on the grounds that Hacker is a complete philistine. I was surprised at Arnold, missing the point like that. After all, the Industry Secretary is the idlest man in town, the Education Secretary’s illiterate and the Employment Secretary is unemployable.

The point is that Hacker, if he were made Minister responsible for the Arts, could hardly start out in his new job by closing an art gallery.

As for Ian, he was either puzzled or jealous, I’m not sure which. He objected that the reorganisation was not meant to be a Cabinet reshuffle. I explained that I was not suggesting a reshuffle: simply to move Arts and Telecommunications into the purview of the DAA.

There is only one problem or inconsistency in this plan: namely, putting arts and television together. They have nothing to do with each other. They are complete opposites, really.

But Arnold, like Ian, was more concerned with all the power and influence that would be vested in me. He asked me bluntly if we wouldn’t be creating a monster department, reminding me that I also have Administrative Affairs and Local Government.

I replied that Art and local government go rather well together – the art of jiggery-pokery. They smiled at my aphorism and, as neither of them could see any other immediate way of calling Hacker to heel, Arnold agreed to implement my plan.

‘Bit of an artist yourself, aren’t you?’ he said, raising his glass in my direction.

[

Appleby Papers NG/NDB/FX GOP

]

Appleby Papers NG/NDB/FX GOP

]

October 11th

Good news and bad news today. Good on balance. But there were a few little crises to be resolved.

I was due to have a meeting with my local committee about the Aston Wanderers/Art Gallery situation.

But Humphrey arrived unexpectedly and demanded an urgent word with me. I told him firmly that my mind was made up. Well, it

was

– at that stage!

was

– at that stage!

‘Even so, Minister, you might be interested in a new development. The government reshuffle.’

This was the first I’d heard of a reshuffle. A couple of weeks ago he’d said it would be just a reorganisation.

‘Not

just

a reorganisation, Minister. A

reorganisation

. And I’m delighted to say it has brought you new honour and importance. In addition to your existing responsibilities, you are also to be the Cabinet Minister responsible for the Arts.’

just

a reorganisation, Minister. A

reorganisation

. And I’m delighted to say it has brought you new honour and importance. In addition to your existing responsibilities, you are also to be the Cabinet Minister responsible for the Arts.’

This was good news indeed. I was surprised that he’d been told before I had been, but it seems he was with the Cabinet Secretary shortly after the decision was taken.

I thanked him for the news, suggested a little drinkie later to celebrate, and then told him that I was about to start a meeting.

‘Quite so,’ he said. ‘I hope you have considered the implications of your new responsibilities on the project you are discussing.’

I couldn’t at first see what rescuing a football club had to do with my new responsibilities. And then the penny dropped! How on earth would it look if the first action of the Minister for the Arts was to knock down an art gallery?

I told Bernard to apologise to the Councillors, and to say that I was delayed or something. I needed time to think!

So Humphrey and I discussed the art gallery. I told him that I’d been giving it some thought, that it was quite a decent little gallery, an interesting building, Grade II listed, and that clearly it was now my role to fight for it.

He nodded sympathetically, and agreed that I was in a bit of a fix. Bernard ushered in the Councillors – Brian Wilkinson leading the delegation, plus a couple of others – Cllrs Noble and Greensmith.

I had no idea, quite honestly, what I was going to say to them. I ordered Humphrey to stay with me, to help.

‘This is my Permanent Secretary,’ I said.

Brian Wilkinson indicated Bernard. ‘You mean he’s only a temp?’ Bernard didn’t look at all pleased. I couldn’t tell if Brian was sending him up or not.

I was about to start the meeting with a few cautious opening remarks when Brian plunged in. He told me, with great enthusiasm, that it was all going great. All the political parties are with the plan. The County Council too. It was now unstoppable. All he needed was my Department’s approval for using the proceeds from the sale of the art gallery as a loan to the club.

I hesitated. ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Well – um . . . there is a snag.’

Wilkinson was surprised. ‘You said there weren’t any.’

‘Well, there is.’ I couldn’t elaborate on this terse comment because I just couldn’t think of anything else to say.

‘What is it?’ he asked.

My mind was blank. I was absolutely stuck. I said things like ‘apparently . . . it seems . . . it has emerged,’ and then I passed the buck, ‘I think Sir Humphrey can explain it better,’ I said desperately.

All eyes turned to Sir Humphrey.

‘Um . . . well. It just can’t be done, you see,’ he said. It looked for a dreadful moment that he was going to leave it at that – but then, thank God, inspiration struck. ‘It’s because the art gallery is a trust. Terms of the original bequest. Or something,’ he finished lamely.

I picked up the ball and carried on running with it, blindly. ‘That’s it,’ I agreed emphatically, ‘a trust. We’ll just have to find something else to knock down. A school. A church. A hospital. Bound to be something,’ I added optimistically.

Councillor Brian Wilkinson’s jaw had dropped. ‘Are we supposed to tell people that you’ve gone back on your word? It was your idea to start with.’

‘It’s the law,’ I whined, ‘not me.’

‘Well, why didn’t you find this out till now?’

I had no answer. I didn’t know what to say. I broke out in a cold sweat. I could see that this could cost me my seat at the next election. And then dear Bernard came to the rescue.

He was surreptitiously pointing at a file on my desk. I glanced at it – and realised that it was the gobbledegook amending Regulation 7 of the Amendment of Regulations Act regulating the Regulation of the Amendments Act, 1066 and all that.

But what was it all about? Cash for Councillors?

Of course

!

Of course

!

My confidence surged back. I smiled at Brian Wilkinson and said, ‘Let me be absolutely frank with you. The truth of the matter is, I

might

be able to get our scheme through. But it would take a lot of time.’

might

be able to get our scheme through. But it would take a lot of time.’

Wilkinson interrupted me impatiently. ‘Okay, take the time. We’ve spent enough.’

‘Yes,’ I replied smoothly, ‘but then something else would have to go by the board. And the other thing that’s taking my time at the moment is forcing through this increase in Councillors’ expenses and allowances. I can’t put my personal weight behind both schemes.’

I waited. There was silence. So I continued. ‘I mean, I suppose I could forget the increased allowances for Councillors and concentrate on the legal obstacles of the art gallery sale.’

There was another silence. This time I waited till one of the others broke it.

Finally Wilkinson spoke. ‘Tricky things – legal obstacles,’ he remarked. I saw at once that he understood my problem.

So did Humphrey. ‘This is a particularly tricky one,’ he added eagerly.

‘And at the end of the day you might still fail?’ asked Wilkinson.

‘Every possibility,’ I replied sadly.

Wilkinson glanced quickly at his fellow Councillors. None of them were in disagreement. I had hit them where they lived – in the wallet.

‘Well, if that’s the way it is, okay,’ Wilkinson was agreeing to leave the art gallery standing. But he was still looking for other ways to implement our scheme because he added cheerfully, ‘There’s a chance we may want to close Edge Hill Road Primary School at the end of the year. That site could fetch a couple of million, give or take.’

The meeting was over. The crisis was over. We all told each other there were no ill-feelings, and Brian and his colleagues agreed that they would make it clear locally that we couldn’t overcome the legal objections.

As he left, Brian Wilkinson told me to carry on the good work.

Humphrey was full of praise. ‘A work of art, Minister. Now, Minister, you have to see the PM at Number Ten to be officially informed of your new responsibilities. And if you’ll excuse me, I have to go and dress.’

‘Another works’ outing?’

‘Indeed,’ he said, without any air of apology.

I realised that, as Minister responsible for the Arts, the Royal Opera House now came within my purview. And I’ve hardly ever been.

‘Um . . . can I come too?’ I asked tentatively.

Other books

Oh Damn One Night of Trouble by Miller, Alice

Household by Stevenson, Florence

Jesse's Brother by Wendy Ely

Warriors in Paradise by Luis E. Gutiérrez-Poucel

Unseen by Caine, Rachel

Sure Thing by Ashe Barker

Ack-Ack Macaque by Gareth L. Powell

Archangel by Gerald Seymour

A Shining Light by Judith Miller

Fury of Obsession (Dragonfury Series Book 5) by Coreene Callahan