The Crisis of Islam: Holy War and Unholy Terror (13 page)

Read The Crisis of Islam: Holy War and Unholy Terror Online

Authors: Bernard Lewis

Tags: #Nonfiction

The other kind of alliance is one based on a genuine affinity of institutions, aspirations, and way of life—and is far less subject to change. The Soviets in their heyday were well aware of this and tried to create communist dictatorships wherever they went. Democracies are more difficult to create. They are also more difficult to destroy.

CHAPTER VI

D

OUBLE

S

TANDARDS

Increasingly in recent decades, Middle Easterners have articulated a more sensitive complaint, a new grievance against American policy: not just American complicity with imperialism or with Zionism but something nearer home and more immediate—American complicity with the corrupt tyrants who rule over them. For obvious reasons, this particular complaint does not often appear in public discourse, nor is it likely to be mentioned in conversations between foreign ministry officials and diplomats. Middle Eastern governments, such as those of Iraq, Syria, and the Palestine Authority, have developed great skill in controlling their own media and manipulating those of Western countries. Nor, for equally obvious reasons, is it raised in diplomatic negotiation. But it is discussed, with increasing anguish and urgency, in private conversations with listeners who can be trusted, and recently even in public—and not only by Islamic radicals, for whom it is a, indeed the, major issue. Interestingly, the Iranian Revolution of 1979 was one time when this resentment was expressed openly. The shah was accused of supporting America, but America was also attacked for imposing what the revolutionaries saw as an impious and tyrannical leader as its puppet. In the years that followed, Iranians discovered that pious tyrants could be as bad as impious tyrants or worse, and that this brand of tyranny could not be blamed on foreign sponsors or models.

There is some justice in one charge that is frequently leveled against the United States, and more generally against the West: Middle Easterners increasingly complain that the West judges them by different and lower standards than it does Europeans and Americans, both in what is expected of them and in what they may expect, in terms of their economic well-being and their political freedom. They assert that Western spokesmen repeatedly overlook or even defend actions and support rulers that they would not tolerate in their own countries.

Relatively few in the Western world nowadays think of themselves as engaged in a confrontation with Islam. But there is nevertheless a widespread perception that there are significant differences between the advanced Western world and the rest, notably the peoples of Islam, and that these latter are in some ways different, with the usually tacit assumption that they are inferior. The most flagrant violations of civil rights, political freedom, even human decency are disregarded or glossed over, and crimes against humanity, which in a European or American country would invoke a storm of outrage, are seen as normal and even acceptable. Regimes that practice such violations are not only tolerated, but even elected to the Human Rights Commission of the United Nations, whose members include Saudi Arabia, Syria, Sudan, and Libya.

The implication of all this is that these peoples are incapable of running a democratic society and have neither concern nor capacity for human decency. They will in any case be governed by corrupt despotisms. It is not the West’s business to correct them, still less to change them, but merely to ensure that the despots are friendly rather than hostile to Western interests. In this perspective it is dangerous to tamper with the existing order, and those who seek better lives for themselves and their countrymen are disparaged, often actively discouraged. It is simpler, cheaper, and safer to replace a troublesome tyrant with an amenable tyrant, rather than face the unpredictable hazards of regime change, especially of a change brought about by the will of the people expressed in a free election.

The “devil-you-know” principle seems to underlie the foreign policies of many Western governments toward the peoples of the Islamic world. This attitude is sometimes presented and even accepted as an expression of sympathy and support for the Arabs and their causes, apparently in the belief that by exempting Arab rulers and leaders from the normal rules of civilized behavior we are somehow conferring a boon on the Arab peoples. In fact this exemption is nothing of the kind, being at the very best a quest for a temporary alliance based on a shared self-interest and directed against a common enemy, sometimes also sustained by a shared prejudice. At a more profound level of reality, it is an expression of disrespect and unconcern—disrespect for the Arab past, unconcern for the Arab present and future.

This approach commands some support in both diplomatic and academic circles in the United States and rather more widely in Europe. Arab rulers are thus able to slaughter tens of thousands of their people, as in Syria and Algeria, or hundreds of thousands, as in Iraq and Sudan, to deprive men of most and women of all civil rights, and to indoctrinate children in their schools with bigotry and hatred against others, without incurring any significant protest from liberal media and institutions in the West, still less any hint of punishments such as boycotts, divestment, or indictment in Brussels. This so-to-speak diplomatic attitude toward Arab governments has in reality been profoundly harmful to the Arab peoples, a fact of which they are becoming painfully aware.

As many Middle Easterners see it, the European and American governments’ basic position is: “We don’t care what you do to your own people at home, so long as you are cooperative in meeting our needs and protecting our interests.”

Sometimes, even where American interests are concerned, American governments have betrayed those whom they had promised to support and persuaded to take risks. A notable example occurred in 1991, when the United States called on the Iraqi people to revolt against Saddam Hussein. The Kurds in northern Iraq and the Shi‘a in southern Iraq did so, and the victorious United States forces sat and watched while Saddam Hussein, using the helicopters that the cease-fire agreement had allowed him to retain, bloodily suppressed and slaughtered them, group by group and region by region.

The reasoning behind this action—or rather inaction—is not difficult to see. No doubt, the victorious Gulf War coalition wanted a change of government in Iraq, but they had hoped for a coup d’état, not a revolution. They saw a genuine popular uprising as dangerous—it could lead to uncertainty or even anarchy in the region. It might even produce a democratic state, an alarming prospect for America’s “allies” in the region. A coup would be more predictable and could achieve the desired result: the replacement of Saddam Hussein by another, more cooperative dictator, who could take his place among those allies in the coalition. This policy failed completely, and was variously interpreted in the region as treachery or weakness, foolishness or hypocrisy.

Another example of this double standard occurred in the Syrian city of Hama in 1982. The troubles in Hama began with an uprising headed by the radical Muslim Brothers. The Syrian government responded swiftly, and in force. They did not use water cannon and rubber bullets, nor did they send their soldiers to face snipers and booby traps in house-to-house searches to find and identify their enemies among the local, civil population. Their method was simpler, safer, and more expeditious. They attacked the city with tanks, artillery, and bomber aircraft, and followed these with bulldozers to complete the work of destruction. Within a very short time they had reduced a large part of the city to rubble. The number killed was estimated, by Amnesty International, at somewhere between ten thousand and twenty-five thousand.

The action, which was ordered and supervised by the Syrian president, Hafiz al-Assad, attracted little attention at the time. This meager response was in marked contrast with that evoked by another massacre, a few months later in the same year, in the Palestinian refugee camps in Sabra and Shatila, in Lebanon. On that occasion, some seven or eight hundred Palestinians were massacred by a Lebanese Christian militia allied to Israel. This evoked powerful and widespread condemnation of Israel, which has reverberated to the present day. The massacre in Hama did not prevent the United States from subsequently courting Assad, who received a long succession of visits from American Secretaries of State James Baker (eleven times between September 1990 and July 1992), Warren Christopher (fifteen times between February 1993 and February 1996), and Madeline Albright (four times between September 1997 and January 2000), and even from President Clinton (one visit to Syria and two meetings in Switzerland between January 1994 and March 2000). It is hardly likely that Americans would have been so eager to propitiate a ruler who had perpetrated such crimes on Western soil, with Western victims. Hafiz al-Assad never became an American ally or, as others would put it, puppet, but it was certainly not for lack of trying on the part of American diplomacy.

Fundamentalists were conscious of a different disparity—another no less dramatic case of double standards. Those whose slaughter in Hama aroused so little concern in the West were Muslim Brothers and their families and neighbors. In Western eyes, so it appeared, human rights did not apply to pious Muslim victims, nor democratic constraints to their “secular” murderers.

Western mistrust of Islamic political movements, and willingness to tolerate or even support dictators who kept such movements out of power appeared even more dramatically in the case of Algeria, where a new democratic constitution was adopted by referendum in February 1989 and the multiparty system officially established in July of that year. In December 1991, the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) did very well in the first round of the elections for the National Assembly and seemed more than likely to win a clear majority in the second round. The FIS had already challenged the Algerian military, accusing them of being more adept at repressing their own people than at helping a brother in need. The brother in need was Saddam Hussein, whose invasion of Kuwait and defiance of the West aroused great enthusiasm among Muslim fundamentalists in North Africa, and persuaded their leaders to transfer their allegiance from their Saudi sponsors to their new Iraqi hero. In January 1992, after an interval of growing tension, the military canceled the second round of elections. In the months that followed they dissolved the FIS and established a “secular” regime, in fact a ruthless dictatorship, with nods of approval in Paris, Washington, and other Western capitals. A bitter and murderous struggle followed, with reciprocal accusations of massacre—of fundamentalists by the army and other less formal instruments of the government, of secularists and modernists and uninvolved bystanders by the fundamentalists. In 1997 Amnesty International assessed the number of victims since the beginning of the struggle at eighty thousand, most of them civilians.

Al-Qa‘ida has held the United States explicitly responsible for the military takeover in Algeria. Here as elsewhere America, as the dominant power in the world of the infidels, was naturally blamed for all that went wrong, and more specifically for the suppression of Islamist movements, the slaughter of their followers, and the establishment of what were seen as anti-Islamist dictatorships with Western—more specifically, American—support. Here too the Americans were blamed—by many for not protesting this violation of democratic liberties, by some for actively encouraging and supporting the military regime. Similar problems arise in Egypt, in Pakistan, and in some other Muslim countries where it seems likely that a genuinely free and fair election would result in an Islamist victory.

In this, the democrats are of course at a disadvantage. Their ideology requires them, even when in power, to give freedom and rights to the Islamist opposition. The Islamists, when in power, are under no such obligation. On the contrary, their principles require them to suppress what they see as impious and subversive activities.

For Islamists, democracy, expressing the will of the people, is the road to power, but it is a one-way road, on which there is no return, no rejection of the sovereignty of God, as exercised through His chosen representatives. Their electoral policy has been classically summarized as “One man (men only), one vote, once.”

Clearly, in the Islamic world as it was in Europe, a free and fair election is the culmination, not the inauguration, of the process of democratic development. But that is no reason to cosset dictators.

CHAPTER VII

A F

AILURE OF

M

ODERNITY

Almost the entire Muslim world is affected by poverty and tyranny. Both of these problems are attributed, especially by those with an interest in diverting attention from themselves, to America—the first to American economic dominance and exploitation, now thinly disguised as “globalization”; the second to America’s support for the many so-called Muslim tyrants who serve its purposes. Globalization has become a major theme in the Arab media, and it is almost always raised in connection with American economic penetration. The increasingly wretched economic situation in most of the Muslim world, compared not only with the West but also with the rapidly rising economies of East Asia, fuels these frustrations. American paramountcy, as Middle Easterners see it, indicates where to direct the blame and the resulting hostility.

The combination of low productivity and high birth rate in the Middle East makes for an unstable mix, with a large and rapidly growing population of unemployed, uneducated, and frustrated young men. By all indicators from the United Nations, the World Bank, and other authorities, the Arab countries—in matters such as job creation, education, technology, and productivity—lag ever further behind the West. Even worse, the Arab nations also lag behind the more recent recruits to Western-style modernity, such as Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore.

The comparative figures on the performance of Muslim countries, as reflected in these statistics, are devastating. In the listing of economies by gross domestic product, the highest ranking Muslim majority country is Turkey, with 64 million inhabitants, in twenty-third place, between Austria and Denmark, with about 5 million each. The next is Indonesia, with 212 million, in twenty-eighth place, following Norway with 4.5 million and followed by Saudi Arabia with 21 million. In comparative purchasing power, the first Muslim state is Indonesia in fifteenth place, followed by Turkey in nineteenth place. The highest-ranking Arab country is Saudi Arabia, in twenty-ninth place, followed by Egypt. In living standards as reflected by gross domestic product per head, the first Muslim state is Qatar, in twenty-third place, followed by the United Arab Emir-ates in twenty-fifth place and Kuwait in twenty-eighth.

In a listing by industrial output, the highest-ranking Muslim country is Saudi Arabia, number twenty-one, followed by Indonesia, tied with Austria and Belgium in twenty-second place, and Turkey, tied with Norway in twenty-seventh place. In a listing by manufacturing output, the highest-ranking Arab country is Egypt, in thirty-fifth place, tying with Norway. In a listing by life expectancy, the first Arab state is Kuwait, in thirty-second place, following Denmark and followed by Cuba. In ownership of telephone lines per hundred people, the first Muslim country listed is the United Arab Emirates, in thirty-third place, following Macau and followed by Réunion. In ownership of computers per hundred people, the first Muslim state listed is Bahrain, in thirtieth place, followed by Qatar in thirty-second and the United Arab Emirates in thirty-fourth.

Book sales present an even more dismal picture. A listing of twenty-seven countries, beginning with the United States and ending with Vietnam, does not include a single Muslim state. In a human development index, Brunei is number 32, Kuwait 36, Bahrain 40, Qatar 41, the United Arab Emirates 44, Libya 66, Kazakhstan 67, and Saudi Arabia tied with Brazil as number 68.

A report on Arab Human Development in 2002, prepared by a committee of Arab intellectuals and published under the auspices of the United Nations, again reveals some striking contrasts. “The Arab world translates about 330 books annually, one-fifth of the number that Greece translates. The accumulative total of translated books since the Caliph Maa’moun’s [

sic

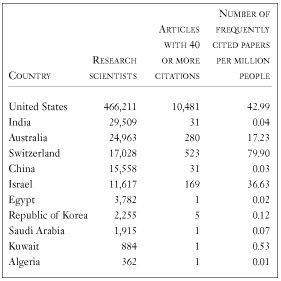

] time [the ninth century] is about 100,000, almost the average that Spain translates in one year.” The economic situation is no better: “The GDP in all Arab countries combined stood at $531.2 billion in 1999—less than that of a single European country, Spain ($595.5 billion).” Another aspect of underdevelopment is illustrated in a table of “active research scientists, frequently cited articles, and frequently cited papers per million inhabitants, 1987.”

1

This is hardly surprising, given the comparative figures for illiteracy.

In a ranking of 155 countries for economic freedom in 2001, the Arab Gulf states do rather well, with Bahrain number 9, the United Arab Emirates 14, and Kuwait 42. But the general economic performance of the Arab and more broadly the Muslim world remains relatively poor. According to the World Bank, in 2000 the average annual income in the Muslim countries from Morocco to Bangladesh was only half the world average, and in the 1990s the combined gross national products of Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon—that is, three of Israel’s Arab neighbors—were considerably smaller than that of Israel alone. The per capita figures are worse. According to United Nations statistics, Israel’s per capita GDP was three and a half times that of Lebanon and Syria, twelve times that of Jordan, and thirteen and a half times that of Egypt.

The contrast with the West, and now also with the Far East, is even more disconcerting. In earlier times such discrepancies might have passed unnoticed by the vast mass of the population. Today, thanks to modern media and communications, even the poorest and most ignorant are painfully aware of the differences between themselves and others, alike at the personal, familial, local, and societal levels.

Modernization in politics has fared no better—perhaps even worse—than in warfare and economics. Many Islamic countries have experimented with democratic institutions of one kind or another. In some, as in Turkey and Iran, they were introduced by innovative native reformers; in others, as in several of the Arab countries, they were installed and then bequeathed by departing imperialists. The record, with the exception of Turkey, is one of almost unrelieved failure. Western-style parties and parliaments almost invariably ended in corrupt tyrannies, maintained by repression and indoctrination. The only European model that worked, in the sense of accomplishing its purposes, was the one-party dictatorship. The Ba‘th Party, different branches of which have ruled Iraq and Syria for decades, incorporated the worst features of its Nazi and Soviet models. Since the death of the Egyptian president Nasser, in 1970, no Arab leader has been able to gain extensive support outside his own country. Indeed, no Arab leader has been willing to submit his claim to power to a free vote. The leaders who have come closest to winning pan-Arab approval are the Libyan Mu‘ammar Qaddafi in the 1970s and, more recently, Saddam Hussein. That these two, of all Arab rulers, should enjoy such wide popularity is in itself both appalling and revealing.

In view of this, it is hardly surprising that many Muslims speak of the failure of modernization and respond to different diagnoses of the sickness of their society, with different prescriptions for its cure.

For some, the answer is more and better modernization, bringing the Middle East into line with the modern and modernizing world. For others, modernity is itself the problem, and the source of all their woes.

The people of the Middle East are increasingly aware of the deep and widening gulf between the opportunities of the free world outside their borders and the appalling privation and repression within them. The resulting anger is naturally directed first against their rulers, and then against those whom they see as keeping those rulers in power for selfish reasons. It is surely significant that all the terrorists who have been identified in the September 11 attacks on New York and Washington came from Saudi Arabia and Egypt—that is, countries whose rulers are deemed friendly to the United States.

One reason for this curious fact, advanced by an Al-Qa‘ida operative, is that terrorists from friendly countries have less trouble getting U.S. visas. A more basic reason is the deeper hostility in countries where the United States is held responsible for maintaining tyrannical regimes. A special case, now under increasing scrutiny, is Saudi Arabia, where significant elements in the regime itself seem at times to share and foster this hostility.