The Crowstarver

Authors: Dick King-Smith

About the Book

Crowstarving was the ideal job for Spider â he was on his own â yet never alone, for all around him were animals of one sort or another.

Discovered as a foundling in a lambing pen, Spider Sparrow grows up surrounded by animals. From sheep and horses to wild otters and foxes, Spider loves them all, even the crows must scare away the newly sown wheat.

Amazingly, every animal who meets Spider implicitly trusts the young boy. This magical rapport is Spider's unique gift, but nothing else in his tough life is so easy.

T

HE

C

ROWSTARVER

Illustrated by Peter Bailey

HAPTER

O

NE

I

nside the shepherd's hut, the only sounds were the chinking of small coals settling in the iron stove and the noisy sucking and occasional half-stifled bleats of a motherless lamb. The shepherd held the orphan upon his lap while he fed it from a titty-bottle, an old brown beer-flagon with a teat on the neck of it.

Outside, in the lambing-pen, there was a constant medley of noise, the crying of lambs mingling with the guttural replies of the ewes, each in her straw-bedded square of hurdles. Accompanying all these sheep sounds was the sough of the wind, a westerly wind that came over the shoulder of the Wiltshire downs and swooped low across the lambing field till it met, and bounded up over, the stout stone

wall that protected the lambing-pen.

Inside this, the ewes that had already given birth and those that the shepherd reckoned were close to their time lay warm and safeguarded from the west wind's buffeting.

The shepherd's hut was a shed-like building with a curved tin roof through which poked a smoking iron chimney, and a small window, golden now from the light of the storm-lantern hung within. The hut was wheeled and shafted, so that it could be drawn from place to place, and in it the shepherd snatched what sleep he could, lying on a rough wooden bunk.

Now, the orphan lamb's needs satisfied, the man stretched himself out and closed his eyes, hopeful of a short nap before he must make his next round of the pens. Over his many years of shepherding he had trained himself to sleep for a quarter of an hour or so whenever he could, through the long nights at lambing time. Below the bunk his dog, a wall-eyed collie, blue merle in colour, laid her head upon her paws.

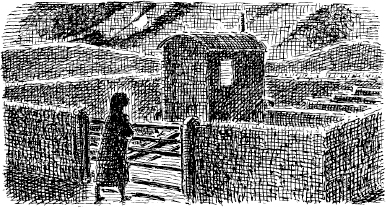

Beside the lambing-pen was a drove, a rough chalk track that carried all the farm traffic from the road in the valley right up onto the downs, and along this drove a figure walked, striving

against the wind. A full moon shone fitfully between scurrying clouds, to show the figure to be that of a young woman, carrying a bundle of some sort.

Coming level with the five-barred gate that gave into the lambing-pen, she opened it, slipped through, and after a gap of some minutes, came out again to turn back down the drove towards the valley road. Maybe it was the force of the wind, now at her back, but the girl's figure looked somehow dejected, head bowed, shoulders hunched, her crossed arms bearing no burden.

Inside his warm hut, Tom Sparrow the shepherd woke suddenly at the sound of his dog's whines. She stood at the hut door tense and alert, and scratched at it with a forefoot.

âWhat's up, Molly?' said Tom. âFox about, is there?' He rose and opened the door, and the bitch ran out and along the line of hurdled pens to the far end, nearest the gate.

As he followed, lantern in hand, the shepherd suddenly heard, amid the high cries of lambs and the deep comforting bleats of ewes, another sound, a quite different sound, a thin wailing. He began to run towards the last pen in the line, beside which Molly stood waiting and wagging.

On Tom's previous rounds, this pen had been empty. Now, as he raised the lantern high, he could see, lying in the bed of wheat straw, what looked like a small bundle of some kind of clothing. It was an old, once white, woollen shawl, the shepherd could now see, and from it came the feeble wailing, and within it, he found as he parted it, was a very young baby.

Quickly Tom picked up the bundle and carried it back to his hut, and laid it in a sack-lined box by the side of the orphan lamb, while he poured milk into an old tin saucepan and put it on top of the stove to heat.

Then, sitting close beside the warmth, he unwrapped the still wailing baby and laid it across his lap, to examine it, as any good stockman inspects any newborn creature, to note its sex, and its state of health, and generally to determine whether it is strong or weak, normal or malformed.

Inside the shawl, the shepherd noticed, was a crumpled sheet of paper. He picked it up and saw, written on it in wavery capital letters, a message. He read this, and then he stuffed the paper into the pocket of his old brown dustcoat, belted around his middle by a length of binder twine.

The baby was a boy, Tom Sparrow could see,

and very young, no more than a few days old, he thought. It was a long thin baby, with none of the healthy pink roundness of the newborn.

Tom held it up before his face and shook his head. âYou'm a poor little rat, you are, my lad,' he said. âBit of a young girl for a mother, I dare say, got pregnant by one of they sojers from the camp, I shouldn't be surprised, and never dared to tell her family. And now she's ditched you. We'll have to try and find her, but first we got to keep you alive.'

At sight of the titty-bottle, filled now with warm milk, the orphan lamb began to bleat.

âWait your turn,' said the shepherd, and applied himself to the task of feeding the human baby. âCome on,' he said, âget it down you, there's a good boy.'

Rather to his surprise, the long thin baby reacted to this order as though it had been understood, and began to suck, gingerly at first and then greedily, at the rubber teat on the neck of the old brown beer bottle held in Tom's right hand.

As he looked down on the baby cradled in the crook of his left arm, his own mouth began to move involuntarily at the sight of those little questing lips, that had seemed bluish but now

became pinker by the minute.

The shepherd had no child of his own, much as he and his wife had wanted one. Whose fault it was that she could not conceive they did not know, and now, after fifteen years of marriage, they had given up hope of parenthood.

But every lambing season Tom, by virtue of his calling, found some unconscious solace in helping to bring into the world so many newcomers, and in saving others, like the lamb bleating in the box beside him, who might otherwise have died. Soon, as soon as one of his ewes dropped a stillborn lamb, he would skin it and fasten the pelt over the orphan, which the ewe, recognizing the smell of her own, would then adopt in place of her dead child. Not only death but the occasional dealing out of merciful death formed part of Tom Sparrow's life, and when a ewe was very old or sick beyond recovery, he would break her neck, with compassion but without fuss.

The essence of his trade however was birth, not death, and now, as he looked down at the sucking baby, he allowed himself a thought which he then spoke aloud to the watching dog. âAh dear, Molly,' said Tom. âI shoulda loved a son.' Gently, tenderly, he touched the palm of one

of the baby's hands with his little finger, dirty as it was and greasy from the ewes' fleeces, and the tiny fingers curled around his and grasped it.

Early on the coming day, before the March sun had yet risen, Kathie Sparrow left her cottage at the road's side. In looks she was very much the archetypal country woman, sturdy, high-coloured, clear-eyed. Oddly, as sometimes happens with man and wife, the Sparrows could have been taken for brother and sister. Each was of middle height, strong-looking, blue-eyed, fair-haired. Now Kathie began to walk up the drove towards the lambing field. She carried a basket in which was her husband's breakfast â bread and cheese and a thermos flask of sweet tea. There were bully-beef sandwiches too, for his midday meal, and then later in the day, towards dusk, she would come again with his supper.

Each lambing season they lived apart, she in the cottage, he in the shepherd's hut, and for them both it was a lonely time, perhaps especially for her, with no child for company. All the other married workers on Outoverdown Farm â the foreman, the horseman, the poultryman, and three of the six farm labourers â had children of their own, as did the farmer himself. Although she was resigned to fate, sometimes Kathie could

not stop herself from wishing that she and Tom had been blessed.

Now, as she walked up the drove in the growing light, she heard the noise of all the young life in the lambing-pen, and she sighed. Oh Tom, she said to herself as she climbed the little steps of the shepherd's hut and opened its door, and then âOh Tom!' as she saw her husband sitting by his stove, a smile on his face, a sleeping baby in his arms.

Putting his hand into his pocket, he drew forth the piece of paper that had been in the shawl, smoothed it out, and gave it to his wife. â

PLEASE SAVE THIS LAMB

' she read.

HAPTER

T

WO

B

y that evening everyone on the farm, everyone in the village indeed, knew that the Sparrows were looking after an abandoned baby, and a number of other people living in the valley had heard about it from the postman or the milkman. But no-one had any clues as to the identity of the mother.