The Crystal City Under the Sea (6 page)

Madame Caoudal’s consent was more difficult to get. But what cannot one achieve with a little perseverance and diplomacy? Worked upon by Hélène, the good lady was induced to confess that, after all, if René wished to employ his leisure in taking a voyage of discovery on his own account, there was no reason why she should oppose it. The young officer now began with all speed to prepare the ways and means for his voyage. He had for the last three weeks been in regular correspondence with some one unknown to the rest of the household. The faithful Kermadec carried the letters to the post-office in the town. For this purpose he went continually backwards and forwards between Lorient and “The Poplars,” proud of serving his officer, big with importance, ready to be cut in pieces sooner than betray a secret, about which, by the way, he knew nothing. It ceased to be a secret when, one morning, René, seating himself at the breakfast-table, handed his mother an open letter, which he begged her to read. The Prince of Monte Cristo had invited him to spend a few weeks on board his yacht Cinderella in order to discuss some new and curious ideas he had formed concerning the flora of the African coast. Everybody knew that the yacht Cinderella had been engaged for several years in sounding in shallow waters. It is a superb boat, commanded by the proprietor in person, and splendidly furnished for the researches he pursues. Many celebrated savants have received his hospitality on board the vessel, and have reported their explorations to the Academies, and registered them in the papers. An invitation to spend several weeks on board so illustrious a yacht could not fail to be considered by Madame Caoudal as a great compliment to her boy.

She certainly did sigh at thought of his sacrificing the rest which he seemed to need; but the satisfaction of knowing that René was about to distinguish himself in a pacific enterprise softened the pang of parting. She therefore, without much persuasion, gave the required assent.

A week later, the young lieutenant, escorted by Kermadec, took the train for Lisbon, where the Cinderella awaited him.

CHAPTER VI

THE YACHT “CINDERELLA”.

T

HE Cinderella (Proprietor and Commander Hereditary Prince Christian of Monte Cristo, the twenty-sixth of his name) was an auxiliary yacht of five hundred and thirty tons. She was schooner rigged, but had also a single screw with engines of three hundred and fifty horse-power, and carried sufficient coal to enable her to steam at full speed for twenty days. Her speed by steam in fair weather was about a dozen knots; but the speed could be considerably augmented by sailing when the weather was favourable. The exterior of the vessel showed a pointed hull, long and light, suggesting the motion of a well-bred horse. The fine proportions of her rigging, the perfect adjustment of her timbers, which enhanced a simplicity full of elegance, struck René’s practised eye at the first glance, inclined though he was by his profession to despise mere pleasure boats as inferior productions. To all appearances, the crew, in its perfect discipline, was copied from that of a man-of-war. The young lieutenant noted with satisfaction the frank and open faces of the men., an unfailing characteristic of men-of-war’s men.

The planks of the deck shone with cleanliness and all the brass was as bright as gold. The officer who received the prince’s guest was less satisfactory than the rest of the yacht. He introduced himself as Captain Sacripanti, second in command of the yacht: He was a little man, short and stout, with black hair shining with pomade, a showy necktie, a double watch-chain ornamented with lockets, and his fingers covered with rings; he looked in fact more like a Neapolitan valet than a seaman. His accent, too,’was that of a flunkey. He was one of those people of doubtful origin, who speak very badly, and with a coarse voice, all the languages of the Mediterranean countries.

Bowing very low, and showing a double row of very white teeth, he offered to conduct the young lieutenant to the commander,—an offer at once accepted. On going aft, René passed, one after the other, a saloon, a smoking-room, a dining-saloon, and a library luxuriously furnished. His guide knocked discreetly at the door of a state-room. “Come in,” cried a voice of thunder. The “second in command “ slid open the door in its groove and effaced himself to allow René to pass. “Lieutenant Caoudal,” he announced in a solemn voice. Upon this, a tall figure emerged from the depths of a monumental arm-chair, and, throwing on a round table the newspaper which he was reading with the aid of eye-glasses, came, with outstretched hand, to greet him:

“My dear M, Caoudal, how pleased I am to see you!” he cried, effusively. And he pressed the young man’s hand within his own, as if he were greeting a long-lost friend. He almost embraced him. Without manifesting any surprise, René expressed to him the pleasure he felt, on his side, at making the acquaintance of the Prince of Monte Cristo.

“Well! do you know, I see we shall get to be as thick as two thieves, upon my word,” cried the prince in an explosive manner, when René had finished speaking, “To begin with, I must tell you I am a very outspoken person. If people please me, I tell them so to their faces. If not,—well, I am equally plain with them. And I like you,—I like you very much. I am positively enchanted to make your acquaintance; enchanted to have you on board for a time; enchanted to find that our work interests you, and that you wish to take part in it. I hope you will enjoy being with us,” continued he with great volubility, paying not the slightest attention to the few polite words the lieutenant felt bound to utter. “If you are not satisfied with anything, you must tell me so, plainly, and I will endeavour to alter, — not my yacht, that would not be practicable, but, at least, I would see that things are rearranged to suit your taste. I wonder how you would like to look over my little wooden shoe, as I call my yacht. Ha! ha! ha!”

Falling in with his host’s noisy, hilarious mood, René declared that he was quite ready to look over the “shoe.” The prince, putting on a huge cap, led the way, and showed him every corner of it, from the deck to the hold, not omitting any detail. René was bound to admit that everything, outside and in, was perfect of its kind. Nothing was wanting which could be useful for the scientific work that the prince had undertaken; photographic studio, carpenter’s shop, forge, physical and chemical laboratory, all seemed admirably organized. Two or three dozen workmen, directed by foremen, occupied these various workshops. The prince said in his guest’s ear, in a stentorian whisper, that they were the pick of jolly fellows, and he “liked them extremely; otherwise he would tell them so squarely, and show them the way out.”

His highness’s appearance was truly extraordinary. Physically, he was a veritable Colossus; tall, broad in proportion, — aldermanic proportion, — very red in the face, with prominent eyes and a large aquiline nose, or, rather, enormous beak, which gave him a fantastic resemblance to a parrot. He had a ringing voice, and gesticulated a great deal; his laugh was Homeric in its amplitude; and his manners, as we have seen, were exuberantly cordial. He affected an openness, a frankness bordering on blunt-ness. An incessant talker, he used a hundred words where ten would have served. But what struck René at the outset was the philosophical disdain he professed on all occasions for the sovereign rank to which he was born. It is true his principality consisted of nothing more than an islet, two or three hundred acres in extent, whose chief industry and sole source of revenue was an argentiferous lead mine, worked by seven or eight hundred convicts, which he let to a neighbouring nation. If he was to be believed, he cared for nothing in the world but personal merit. He affirmed that the meanest scavenger, if intellectually endowed, was worth more to him than an emperor on his throne. One would have thought that he wished, by this ostentatious display of principles, to excuse himself for

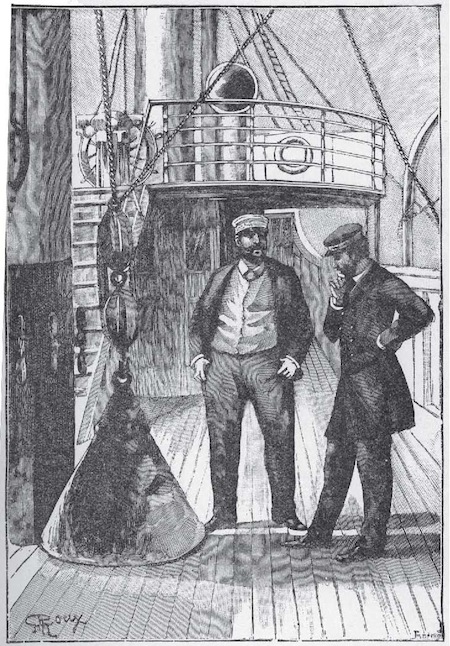

On board the “Cinderella”.

having been born some fifty years previously heir to a large fortune as well as a princely crown. At least he had the good taste to spend a good third of it in useful scientific work.

“I look upon myself as a steward,” he volunteered. *’My fortune is not my own. I only manage it for the benefit of those who have none. As to my name! bah! what is that? As the immortal Shakespeare says, ‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.’ I protest to you that I attach no importance whatever to it, and that I would as soon go by the name of Big John, as Monte Cristo,” But he never missed an opportunity of reminding one of the twelve hundred years of ancestors more or less authentic. In five minutes René knew him through and through. Ridiculous though he was, he could not dislike him, and the prospect of spending a few weeks on board so charming a vessel was not to be despised. The prince insisted on himself showing him to his cabin. It was most elegant and commodious, and opened on the library. He begged the young fellow to consider himself at home, and to tell him if he would like anything altered to suit his convenience. René assured him in all sincerity that he had never been so comfortably lodged, and they went up on deck the best friends in the world.

The object of the present voyage of the Cinderella was to sound some of the Atlantic shoals, and René lost no time in asking to be shown the apparatus to be used for the purpose. The investigation had an interest for him little dreamt of by Monte Cristo, who took him at once to the place where it was standing ready for use. It was an enormous block of lead, weighing twenty tons; round its upper extremity was coiled a solid rope of measuring silk, which Monte Cristo pronounced, not without pride, to be five hundred yards in length.

“You see,” said the prince, much pleased at being able to play the showman, “our monstrous plummet is hollowed out at the base, and has a coating of grease. When it has lain long enough at the bottom it is slowly drawn up by means of this windlass; it reappears covered with shells, gravel, grasses, débris of all sorts which it picks up in dragging along at the bottom of the sea. It is by studying the nature of this débris with the magnifying-glass that we draw our conclusions concerning the kinds of vegetable and animal life (often new to us) concealed in, these beds under water.”

“Indeed!” said René, surprised and disappointed, “have you no other method of research?”

“Why, no, my dear fellow! What more would you have than a plummet like mine? What do you find defective in it?”

“Nothing in itself, certainly. It is a superb plummet, but, if I may be permitted to make a suggestion, it is that another machine, somewhat akin to it, be used for examining the sea-bottom.”

“But what sort of machine would you suggest? Would you have me send a photographic camera a thousand feet under water? And by what means, may I ask?”

“A camera? no.”

“What, then?”

“A man! Yes, I confess, sir, I should not have asked to join in your researches, if I had not indulged the hope of going myself to the sea-bottom. I cling to the hope of seeing, with my own eyes, what goes on down there, and all the shells that could possibly attach themselves to the largest plummet in the world would tell me absolutely nothing! The least glance in person would serve my purpose.”

“He, he!” and the prince went off in an explosion of laughter. “I dare say, my young friend; I, too, should like extremely to see, with my own eyes, what is going on among the fishes. But just one thing stands in my way, you see. It is impossible, simply impossible!”

“Why impossible?”

“For a very good reason; namely, that we make our soundings at such depths that we could not possibly provide our divers with a respiratory tube long enough, and, if we sent our men to explore the depths, what steps could we take to provide them with air to breathe?”

René reflected a minute before replying.

“It is clear that the difficulty of providing respirable air is the only thing that stands in the way,” said he, at last. “ Well, if we cannot make a tube sufficiently long, we must think of some other expedient, that’s all.”

“Hum, ha! let us see,” said the prince, crossing his arms on his ample chest.

“Look here; it will be necessary, according to my idea, to contrive a special diving apparatus; an apparatus for shoal soundings. If only a supply of respir-able air, sufficient to last for three or four hours, could be assured to the diver! Round the suspension cable a telephonic wire should be coiled, which should keep the explorer in communication with those on deck, so that he could be drawn up as soon as he gives the word, and, in case he gave no sign of life after a given interval, he could be drawn up, without losing a minute, by means of a steam-engine.”

“Do you know, that is the most ingenious plan I ever heard of!” cried the prince, enchanted, “only we have no such diving apparatus.”

“That is true.”

“What, then?”

“We must invent one. Haven’t you here. on board, complete workshops, and first-rate workmen?”

“Certainly; there are none better than mine, I flatter myself.”

“Very well; with your permission, I will at once set to work in the library, and begin to work out my plan of a diving apparatus, and I hope, before long, to make drawings exact enough for your workmen to construct a most satisfactory one.”