The Crystal City Under the Sea (8 page)

“Then what can I do to please you?”

“Acknowledge the delicate reserve of a man whom you honour,” said Mademoiselle Luzan, gravely, “and who is the only one—”

“The only one—?”

“That you will ever marry,” added Bertha, smiling.

“It will be in spite of himself, then,” said Hélène. “Confess, now, that it would be impossible to manifest less eagerness than he does.”

“As if you did not know as well as I, that it is your fortune that paralyzes him, to say nothing of your aunt’s plans for you, which are no secret from any one.”

“That would be a very good reason; reasonable enough for any one but Stephen, who has heard us a dozen times, Ren6 and me, explain ourselves clearly on that point. As to the mere accident of dowry or fortune, it is unworthy of such a man as he to attach such importance to it,”

“Do not say so, Hélène,” replied Mademoiselle Luzan, gently. “You cannot know how odious it would be to a proud man to appear calculating in such a matter.”

“But if I do not believe he would be calculating, what does it matter what other people think?”

“Still, I think you ought to let him know.”

“In other words, I am to make advances to him? Never! If he has n’t the courage to overcome such a miserable obstacle,—well, we must remain apart. He is of no less value in my eyes for being without a fortune, and I feel no more inclined to propose marriage to him, than I should to no matter what great personage.”

“Brave heart! “ said Bertha, embracing her; “but take care, Hélène, don’t be hard and unjust. He, whom you are keeping at a distance, is sadly misunderstood.”

“Misunderstood? So be it!” said Hélène, decidedly. “What can I do?”

“It is a misunderstanding that a word could put right,” said Bertha, dreamily to herself, and, without insisting any more, she came back to the subject on which they never disagreed, the cruise of the yacht Cinderella and the great work Rend was doing.

The very moment the two friends were discussing his plans and wishing him success, the young lieutenant was embarking on his first descent in the submarine cabin he had designed. Comfortably installed at his writing-table, over which was placed a chronometer, an aneroid barometer, a thermometer, and a dial-plate for registering the length of cable paid out by the steam capstan, he recorded with a steady hand his slightest impressions, that he might transmit them to his family. And the following is what was written on the first pages of the “ Journal of a Diver:”

René’s Journal.

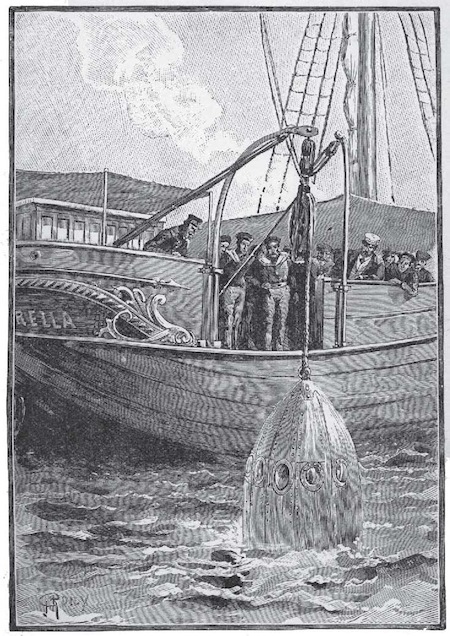

“June 11th. 17 minutes past 12 P. M. Longitude, 24° 17' 23" East; Latitude, 30° 40' 7" North. Here I am, sealed up in my cell for my first descent. The fastenings of the door and of the port-holes appear to be quite water-tight. All is in order and everything in its place. I have poured into the tub thirty pints of water of baryta, the oxygen flagon is ready to act. The electric light is all one could wish. Off we go! I sound the telephone, and give the order to start; ‘Reel off twenty-five yards! Au revoir, gentlemen’—It is done. The only sounds I hear are the steam-engine above my head, and the movement of the hand on the dial registering my descent; otherwise all is as smooth and insensible as can be wished. At the precise moment when the needle marks twenty-five yards, it stops. All is going capitally, I telephone that message, and receive in reply the echo of my host’s sonorous congratulations. A rapid glance through each port-hole shows me clear green water all round me; excepting that through the roof I distinguish the keel of the yacht and its shadow. Not the slightest oozing at the joints; the caulkers of the Cinderella are first-rate, like all the workmen on board.

“12.20. Gave the order to pay out a hundred yards more cable.

“12.22. The needle points to one hundred and twenty-five, and stops. The water is opaque and dark. In the rays of electric light projected to

The first descent of the diving-bell.

larboard I see file past me huge fish, terrified by this submarine light. Telephoned: ‘All going well. Pay out three hundred yards!’

“12.28. The needle marks four hundred and twenty-five yards. Around me the water is black. Not a ray of sunlight can pierce the gruesome wall interposed between the atmosphere and my cell. Is it an illusion? It seems to me that the silence is more intense, more complete, more black, so to speak, than at the start. That is the only difference. The air of the room does not appear to have suffered any appreciable modification. The temperature is stationary. Telephoned; ‘Pay, out Jive hundred yards, slowly, ready to stop at the first call!’

“12.36. Needle marks seven hundred and forty yards. Telephoned: ‘Slow down the paying out of the cable, gently, and with attention!’

“12.38. I did right to go slowly. A pretty rough shake informed me that I had reached the bottom. Telephoned: ‘Stop!’ The order is executed in less than a twentieth of a second. The needle points to nine hundred and thirty-four yards. Thus, the descent has not taken more than twenty-one minutes. I feel the strange sensation of arriving on shore after a voyage, and finding dry land once more,—a singular illusion, truly, at a distance of one thousand yards below the surface! Can it be that the bottom of the sea is my real country, my home? Telephoned: ‘All well! Have touched the bottom. Nine hundred and thirty-four yards.’ Answer: ‘A volley of cheers.’ Replied; ‘Thanks; but leave me to explore the country.’

“The floor of my cabin is horizontal, proving that the diving-bell has grounded on a flat surface. Indeed, the electric light dispersed to right and left, and before and behind, reveals a bed of sand and calcareous débris. Everything is dead, bleached, and motionless. Nothing in the least resembling nursery tales or poets’ songs. Nothing could be less like the famous dream of Clarence.

“‘Methought I saw a thousand fearful wrecks;

A thousand men that fishes gnawed upon;

Wedges of gold, great anchors, heaps of pearl,

Inestimable stones, unvalued jewels,

All scattered at the bottom of the sea:

Some lay in dead men’s skulls.’

1

“No skull, and not the ghost of a pearl here! Nothing, alas, to tell of the neighbourhood of a human being! Nothing but the impalpable dust of molluscs of past ages. What matter? Now is the time for me to try the tentacles of my diving-bell, and to prove their superiority over the greased plummet of former soundings. They are a little short, these india-rubber arms of mine! It is with great difficulty that I have been able to pick up a handful of débris. Débris which the impermeable glove has faithfully brought me, notwithstanding; and which I have succeeded in bringing into the cabin by turning the sleeve or huge finger, and shutting it by means of its obturators, which I provided for detaching the glove and warehousing the collection, nothing worth picking up after all, except as a specimen of what can be gathered by a human hand at a depth of twenty-eight hundred feet, and to provide a month’s work for Monte Cristo’s microscope. Improvement suggested: lengthen the india-rubber arms of my diving-bell, and provide them with elementary tools, spade, hammer, and pincers, to be attached to the outside wall of the diving-bell. Sounds in the telephone: ‘Halloo! halloo!’ What do these worthy people want? Monte Cristo appears to be getting impatient, and wondering if I am dead. ‘Not yet! I am going to give the order, presently, to be drawn up: “Time to take a few more notes. Respirable air without appreciable change; oxygen in plenty; thermometer risen two degrees and three-tenths. Atmospheric pressure stationary since the start. Come! decisive experience has been gained; the only thing, now; is to go back on board, and make another attempt another day.

“12.57. ‘Halloo! halloo!’ Sh—The order is given to draw up. Sh — We are tripping anchor. We are shaken a little bit, but nothing to speak of; the bottom of my cabin emerges from its bed of sand; then a continued noise of water swishing past the walls of the diving-bell, which rises and rises, while the needle goes back on the dial, instead of stopping, by reason of our speed of fifty yards per minute. Telephoned; ‘All right! but increase the pace a little.’ It is going now at eighty yards a minute. The needle points at six hundred and fifty.

“1.13. A noise of dripping on all sides. A cheer from the crew. Here I am again, lifted up in sixteen minutes. I have nothing to do but draw the bolt and jump on deck.”

CHAPTER VIII

THE DIVING BELL.

T

HE crew of the Cinderella welcomed the return of the audacious explorer with enthusiastic joy. During his short sojourn on board the yacht, René had made himself liked by all; and workmen and sailors had awaited with keen anxiety the result of the hazardous experiment. Monte Cristo, himself, had felt his princely heart beat rather more quickly as the intrepid officer disappeared in the abyss. Therefore, he felt sincere emotion on seeing him come back; he ran to him and pressed him in his arms. “Champagne for everybody to drink M. Caoudal’s health!” he said to Sacripanti, who bowed and obeyed the order without delay. “ And you, my dear hero, must be famished, I ‘m sure.”

“You are right; I am voraciously hungry,” replied the lieutenant; “but that is between ourselves, however. I could never have believed I should be prey to such nervous excitement. My pulse beats so fast, I almost thought I could live on air, but, now you mention it, the void in my inner man destroys that illusion.”

“Come, come! your sang-froid is simply admirable. Do not undervalue yourself, but let us sit down to the lunch you have so well earned.”

While they did justice to the lunch, René gave his host an account of the main facts of the journey, and gave him the specimens he had brought up with him. The prince was delighted, and already foresaw a series of discoveries—by proxy—glorious for the yacht and for himself. He passed the rest of the day at his microscope in a state of feverish agitation, which contrasted with the calm demeanour of the young lieutenant.

The next day René got to work again, accomplishing, every day, three or four fresh descents, in order to take separate bearings, with the greatest care, at distances of two or three marine miles. Sometimes the state of the water made the operation impracticable. There was then nothing for it but to wait, and René was tortured with impatience. Although his researches had, so far, brought him no satisfactory result, his conviction remained unshaken that the mysterious subterranean dwelling which had sheltered him for some few never to be forgotten hours, or minutes, ought to be situated between the Sargassian Sea and the Azores. To explore that vast region, to sound successively every part of it,— such was the intrepid (mad, some would say) project he conceived and pursued with indefatigable perseverance.

No one else knew of this plan but Hélène. René looked upon her as the only person capable of believing in the reality of his adventure. And if he needed encouragement, it was in that direction that he found it, in the youthful imagination, largeheartedness and characteristic good sense of the unsophisticated girl. But he had something better still—faith—the lever which removes mountains and triumphs over difficulties. That was why, notwithstanding all obstacles, he accomplished his end, Monte Cristo began to wonder at the tenacity with which his young and distinguished collaborator, as he called him, not without a shade of patronizing fatuity, set himself to repeated expeditions having no apparent result; for the india-rubber arms of the diving-bell had not brought up any hitherto unknown animal or vegetable variety.

But there was one man on board who grew more and more curious day by day; and that was Sacripanti. The Levantine rapacity of his mind could not believe that Caoudal exposed himself every day to such danger for any purely scientific object. The conviction took hold of him, little by little, that the lieutenant must be possessed of precise and particular information respecting some treasure submerged near the Azores,—a galleon, perhaps, laden with piastres and sunk for centuries under the weight of its riches; or, who could tell? an old vessel from the East Indies, whose rotten planks concealed beneath the waves a cargo of diamonds and rubies. Nothing but the attraction of so much wealth could account for Caoudal’s perseverance. At this idea Sacripanti’s black eyes glittered; his sallow face flushed with avarice; he swore between his white teeth that, in one way or other, he would have his share of the windfall.

His first manoeuvre in that direction was not a happy one. After having loaded René, as his custom was, with nauseous flattery in reference to his unrelaxing heroism, he suggested that these expeditions would be less monotonous if M. Caoudal had a companion. “Perhaps, without having to look very far,” added he, trying to assume a modest manner, but one which was only abject, “perhaps you might find, on board, a man whose devotion to science might equal your own, and who would feel honoured at serving you as your pupil, or even to help manoeuvre —” To which Caoudal replied that he thanked Captain Sacripanti for his obliging offers, but that the submersible chamber was constructed to accommodate one passenger only. Baffled on that head, the “second in command” tried another plan, and began systematically to excite the jealousy of his employer.