The Day of Battle (30 page)

Authors: Rick Atkinson

Tags: #General, #Europe, #Military, #History, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War, #World War II, #World War; 1939-1945, #Campaigns, #Italy

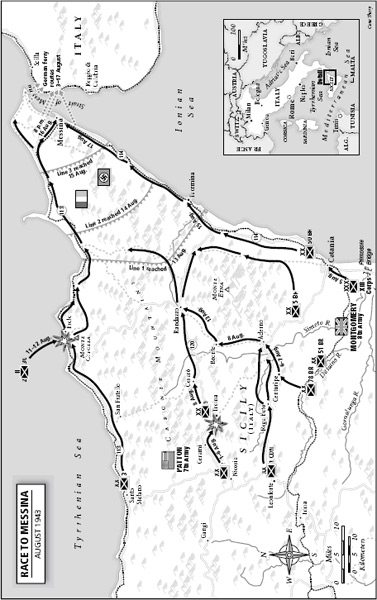

Italian commanders quickly got wind of the evacuation scheme and began their own measured withdrawals on August 3. Without informing Berlin or awaiting Hitler’s approval, Kesselring authorized Operation

LEHRGANG

—“Curriculum”—to begin at six

P.M

. on Wednesday, August 11, just as Bernard’s battalion was fighting for survival at Brolo. The Hermann Göring Division went first, under a flotilla commanded by the former skipper of the airship

Hindenburg;

hundreds of shivering malaria patients also huddled on the ferries for the thirty-minute ride across the strait at six knots. Oil lamps flickered on the makeshift piers. Overhead screens shielded the glare from Allied pilots, but every anxious

Gefreiter

stared upward and listened for the sound of the B-17 bombers that would blow them to kingdom come.

The B-17s never came. Allied commanders had had no coordinated plan for severing the Messina Strait when

HUSKY

began, nor did any such plan emerge as the campaign reached its climax. Inattention, even negligence, gave Kesselring something his legions never had in Tunisia: the chance for a clean getaway.

British radio eavesdroppers had picked up many clues as early as August 1, including ferry assignments for the four German divisions, and messages about stockpiles of fuel and barrage balloons. But AFHQ intelligence in Algiers on August 10 found “no adequate indications that the enemy intends an immediate evacuation,” although General Alexander had noted signs of withdrawal preparations a full week earlier, in a cable to Admiral Cunningham and Air Marshal Tedder. “You have no doubt co-ordinated plans to meet this contingency,” Alexander added. It was left to Montgomery to belabor the obvious: “The truth of the matter is that there is

no

plan.” Not until ten

P.M

. on August 14, four days into the evacuation, did Alexander signal Tedder, “It now appears that [the] German evacuation has really started.” Only a few hours earlier, AFHQ had again reported “no evidence of any large-scale withdrawal.”

Allied pilots had reason to fear the “fire canopy” that Baade’s guns could throw over the strait. But his antiaircraft guns, if plentiful, lacked range. The entire initial production run of the new German 88mm Flak 81, which could reach the rarefied altitude of 25,000 feet and higher where the B-17 Flying Fortresses flew, had been lost in Tunisia. Yet air commanders were reluctant to divert the Allied strategic bomber force, which included nearly a thousand planes, from deep targets in Naples, Bologna, and elsewhere. To be sure, swarms of smaller Wellingtons and Mitchells, Bostons and Baltimores, Warhawks and Kittyhawks raked the strait. Little sense of urgency obtained, however: of ten thousand sorties flown by bombers and fighter-bombers in the Mediterranean from late July to mid-August, only a quarter hit targets around Messina. B-17s attacked the strait three times before

LEHRGANG

began; yet, as the Axis evacuation intensified on August 13, the entire Flying Fortress fleet was again bombing Rome’s rail yards.

Naval commanders had equal reason to shy from Baade’s ferocious shore batteries and “the octopus-like arms of searchlights.” Admiral Cunningham in Tunisia had famously decreed, “Sink, burn, and destroy. Let nothing pass”; here, he issued no such commandment. “There was no effective way of stopping them, either by sea or air,” Cunningham said, and Hewitt agreed. Patrol boats and small craft staged nuisance attacks, but both British and American admirals declined to risk their big ships. “The

two greatest sea powers in the world,” the strategist J.F.C. Fuller wrote, “had ceased to be sea-minded.”

Not once did the senior Allied commanders confer on how to thwart the escape. Increasingly preoccupied with the invasion of mainland Italy in September, they never urged Eisenhower to divert his strategic bombers and other resources for a supreme effort. Nor did he force the issue. On August 10, alarmed at signs of exhaustion, the commander-in-chief’s doctors ordered him to bed. There he remained for three days, “as much as his nervous temperament will permit,” Butcher noted. Perhaps sensing the missed opportunity, Eisenhower on Friday morning, August 13, “hopped in and out of bed, pranced around the room, and lectured me vigorously on what history would call ‘his mistake,’” Butcher added—the failure to land

HUSKY

forces “on both sides of the Messina Strait, thus cutting off all Sicily.”

“It is astonishing that the enemy has not made stronger attacks in the past days,” the commander of the Messina flotilla, Captain Gustav von Liebenstein, told his war diary on August 15. The evacuation was so unmolested that crossings soon took place by day, exploiting “Anglo-Saxon habits” during the early morning, lunch hour, and tea time. The Italian port commander departed Messina on August 16 after setting time bombs to blow up his docks. Two hundred grenadiers held a crossroads four miles outside the city, then fell back to board the last launches; German engineers cooled a wine bottle by towing it in the sea, and drank a toast as they neared the Calabrian shore. An eight-man Italian patrol inadvertently left behind was plucked from the shore by a German rescue boat at 8:30

A.M

. on Tuesday, August 17, just as Allied troops converged on Messina.

They were among 40,000 Germans and 70,000 Italians to escape. Another 13,500 casualties had been evacuated in the previous month. German troops also carried off ten thousand vehicles—more than they had brought to Sicily, thanks to unbridled pilferage—and forty-seven tanks. The Italian evacuees included a dozen mules. “The Boche have carried out a very skillful withdrawal, which has been largely according to their plan and not ours,” a British major noted.

Kesselring declared the German units from Sicily “completely fit for battle and ready for service.” That was hyperbole; since July 10, Axis forces had been badly battered, by the Allies and by malaria. But those escaping divisions—the 15th Panzer Grenadier, the 29th Panzer Grenadier, the 1st Parachute, and the Hermann Göring—would kill thousands of Allied soldiers in the coming months. “We shall now employ our strength elsewhere,” Captain von Liebenstein wrote as he reached the mainland, “fully trusting in the final victory of the Fatherland.”

At ten

A.M

. on August 17, Patton arrived on the windswept heights west of Messina where Highway 113 began a serpentine descent into the city. Waiting on the shoulder, Truscott tossed a welcoming salute. As in Palermo, he had been ordered not to enter the town before his army commander, and Truscott earlier this morning had rejected the surrender proffered by a delegation of frock-coated civilians. A platoon from his 7th Infantry had reached central Messina at eight o’clock the evening before, swapping shots with stay-behind German snipers, until a Ranger battalion and other U.S. troops arrived with orders “to see that the British did not capture the city from us.” By the time a colonel from Montgomery’s 4th Armoured Brigade arrived, with bagpipes and a Scottish broadsword in the back of his jeep, the Yanks had staked their claim. Bradley was furious upon hearing that Patton had organized his own hero’s entry even as some enemy troops remained on Sicily. “I’ll be damned,” he said. “Now George wants to stage a parade into Messina.”

Patton had a fever of 103 from a lingering case of sandfly fever, and Bradley’s sentiments concerned him not at all. The race to Messina was won; the campaign for Sicily was over. On a concrete wall above the highway the word “DUCE” was painted in white letters big enough to be seen from the Italian mainland. Hazy Calabria lay across the strait, whose waters were home to Scylla, twelve-footed, six-headed, barking like a puppy while she devoured half a dozen of Odysseus’ oarsmen. German shells fired from the far shore spattered into Messina below or raised towering white spouts in the harbor. “What in hell are you standing around for?” Patton demanded.

Down they raced through the hairpin turns at breakneck speed, an armored car and Patton’s command vehicle leading the cavalcade. “Doughboys were moving down the road towards the city,” noted Lucas, who had arrived with Patton’s entourage. “They were tired and incredibly dirty. Many could hardly walk.” A shell slammed into the hillside above the highway, wounding a colonel and several others in the third car of the procession. Patton sped on.

Messina was a poor prize. Sixty percent of the city lay in ruins, the cathedral roof had collapsed, and German troops had booby-trapped door handles, light switches, and toilet cisterns. Enemy fire whittled the buildings still standing. Shells dislodged caskets from their wall niches in one cemetery, scattering skeletons among the Rangers who had bivouacked there. American artillery now answered, and a 155mm gun named Draftee fired the first Allied shell onto the Italian mainland. Millions would follow.

Although three-quarters of Messina’s 200,000 citizens had fled the city, a throng lined the streets to greet Patton. Clapping solemnly, they tossed grapes and morning glories. At the city hall piazza, in a ragged ceremony expedited by howling shell fire, the mayor formally tendered Messina to the conquerors.

“By 10

A.M

. this morning, August 17, 1943, the last German soldier was flung out of Sicily,” Alexander cabled Churchill, “and the whole island is now in our hands.”

A deflated Patton was more prosaic in his diary entry that Tuesday afternoon: “I feel let down.”

He soon would feel worse. At noon on the same day, as the Messina ceremony concluded, Eisenhower in Algiers was rereading a detailed account of the slapping affair that had been sent directly to the AFHQ surgeon general by a medical officer in Sicily. Corroboration soon came from several incensed reporters who had quickly pieced together the story and alerted Harry Butcher and Beetle Smith. “There are at least fifty thousand American soldiers who would shoot Patton if they had the slightest chance,” Quentin Reynolds of

Collier’s

advised Butcher. Ushered into the commander-in-chief’s office at the Hôtel St. Georges, Demaree Bess of the

Saturday Evening Post

told Eisenhower, “We’re Americans first and correspondents second.” But striking a subordinate was a court-martial offense. “Every mother would figure her son is next” to be slapped, Bess added. Sympathetic to Eisenhower’s dilemma over how to handle his most aggressive field commander, the reporters agreed to kill the story “for the sake of the American effort.” British hacks showed similar restraint; of the sixty Anglo-American reporters in Sicily and North Africa, not one wrote a word.

Eisenhower agonized through several sleepless nights. Patton was selfish, he declared while pacing in Butcher’s bedroom one evening, and willing to spend lives “if by so doing he can gain greater fame.” Still, he added, “in any army one-third of the soldiers are natural fighters and brave. Two-thirds inherently are cowards and skulkers. By making the two-thirds fear possible public upbraiding such as Patton gave during the campaign, the skulkers are forced to fight.”

Such dubious arithmetic hardly excused reprehensible behavior, and Eisenhower’s five-paragraph letter of censure, delivered to Patton by the AFHQ surgeon, was harsh:

I must so seriously question your good judgment and self-discipline as to raise serious doubts in my mind as to your future usefulness…. No letter that I have been called upon to write in my military career has caused me the mental anguish of this one.