The Day the Falls Stood Still (24 page)

Read The Day the Falls Stood Still Online

Authors: Cathy Marie Buchanan

Tags: #Rich people, #Domestic fiction, #World War; 1914-1918, #Hydroelectric power plants, #Niagara Falls (Ont.)

L

ate afternoon I sit on the back stoop of our very own May Avenue house peeling apples for a pie. Jesse is busy kicking up the leaves trapped in the nook between the cellar door and the stoop. Francis is fully engaged by the fluttering leaves, and so I ignore the heaviness of the diaper drooping between his thighs.

I glance up the bluff and see Glenview’s freshly painted eaves, also the pediment window that is no longer cracked. I do not know the people who live there, only that their name is Haversham and that their daughter gallops around the yard in lovely dresses much as Isabel and I had. Once when Mother was visiting, we went up to the house, ostensibly to leave a business card, though I suspect she had it in her head Mrs. Haversham would make a more suitable friend for me than any of the half dozen Italian neighbor women I have met. It would explain why Mother had washed and pressed her one decent dress the evening before and then badgered me into changing from my best housedress into a pretty frock that would have been just right had we been summoned up the bluff to tea before the hemlines had risen from ankle to calf. In the end, it had not mattered. A housekeeper answered the knocker, asked why we were calling, and, once I had handed over my business card, promptly shut the door.

But even if Mrs. Haversham had opened the door and mistaken me as someone belonging to her set, even if I were invited in, my isolation would have remained much as it is. I am stuck somewhere between my new life and my old, not truly fitting in with my Silvertown neighbors, who grow tomatoes in their front yards and collect dandelion greens from the side of the road and haggle with the ice cart driver though the price is set, not truly fitting in with society. After running into Lucy Simpson, whom I had been friendly with at Loretto, that much had become abundantly clear. She had astonished me by inviting me to a luncheon at her house. “You’ll know everyone,” she said.

I gathered she meant the guests had gone to Loretto and said, “Will Kit be there?”

“She isn’t much for parties midafternoon. She prefers work. Poor Leslie, with half the town thinking he can’t support his wife.”

“Everyone knows he’s with the Hydro, the chief hydraulic engineer,” I said, a little bewildered to find myself irked on Kit’s behalf.

“Well?”

“I’ll have to see about arrangements for the boys,” I said. It was an excuse.

“Come,” Lucy said. “You can tell us all about your famous Tom Cole.”

And then in the evening, Tom said, “You should go. You could use a friend.” It was not anything I had not thought myself. Still, hearing it aloud made me feel pitiable, and I had no wish to be, and so I nipped and tucked and fussed over one of Isabel’s old dresses and set off for a luncheon I did not much want to attend.

In Lucy Simpson’s grand dining room, I told the boys’ ages and said that, yes, of course I was afraid when Tom was out there on the ice bridge. There were more questions, about other rescues, and then finally about the bodies he pulls from the river. Lucy called them floaters and made a joke about the stink, and I knew there was no point trying to explain about the care he took. It bothered me, too, her tactlessness, the way it seemed she had entirely forgotten about Isabel, and I began making less of an effort to join in, which was hardly a chore. I had nothing to say about the latest ball at the Clifton House and I had not traveled to New York and I knew nothing about the fund-raising dilemmas of the Lundy’s Lane Historical Society. Nor would my old classmates have wanted to hear that I had found a yard goods shop in Toronto that carried lace from Burano, Italy, for a fair price, even less so that Garner Brothers hardware had washboards on sale for sixty-five cents. It occurred to me, afterward, that Kit would have saved me from the banality, and it caused me to miss her very much.

I walked home by way of Erie Avenue and peered into each of the shops the Atwells owned, looking for her. But no matter that for once I had worked up the resolve to talk to her, even plead, if that was what it took, she was nowhere to be seen, even as I made a second pass, daring to step into each of the shops.

A

fter a while Francis grows bored with the fluttering leaves and his squawks become insistent. I whisk him into the house and set him on the bench that substitutes for kitchen chairs. In the way of furnishings we have little more than the tablecloths and serviettes from the trousseau Mrs. Andrews had given us. One hand on his belly, I deftly unfold a clean diaper and slide it under his bottom. While I rinse and wring the old diaper, I balance him on a hip and glance around wistfully, thinking I should put the apples aside a moment and get the breakfast dishes cleaned up. And the floor needs to be swept. And the stove needs to be blackened yet again. When he rubs his eyes, I return to the stoop, hoping he will nurse. If I am lucky, he will drift off and the apples will be peeled and the dishes washed and the floor swept before Tom comes in from work. The stove will have to wait.

Six days a week I sew from early morning straight through to midafternoon. I am able to manage it only because a neighbor called Mrs. Mancuso looks after the boys. Under her watchful eye, Jesse has learned to differentiate basil from mint, and to say when a tomato is ready to be picked. He can turn the handle of a pasta machine and knows

fusilli

is like a corkscrew and

penne

like a tube. She coddles them, though. For instance, she shoos the boys out the door after lunch and clears the table herself, which means I am back to reminding Jesse to put his dirty dishes in the sink. And he does not see why he should eat beef stew for supper, not when Mrs. Mancuso made him meatballs for lunch after he turned up his nose at the macaroni she had first served. But there is never a fuss in the morning when we walk to her house, and the boys are returned to me midafternoon clean and well-fed. What is more, her house is only an empty lot over from our own.

When there is more sewing than I can manage, I save the handwork for the evenings. On occasion I have sat overcasting what seems a never-ending stream of buttonholes and thought I would like to take on less work. But we have agreed to the schedule of repayment set out in our mortgage contract, and the expense is large, mostly on account of my long list.

I

n the evening, I collect a blouse with cuffs to be hand-stitched from the sewing room and head for the kitchen, where I expect to find Francis contentedly toppling blocks, and Tom and Jesse playing dominoes or Chinese checkers, or whooping it up with Tom on his knees and Jesse on his back. But Tom is alone, sitting at the kitchen table, writing in a small notebook. “Where are the boys?” I say.

“The Mancuso girls were over, begging to take them for a walk.” He closes the cover of the notebook.

I slide in beside him on the bench and poke my chin toward the notebook.

“It’s nothing,” he says.

I move a hand toward the notebook but stop short. “Nothing?”

“I’m tracking the river’s height at a couple of spots.”

“Some sort of record?”

He nods, and the nod seems sheepish, as though there is a good chance I will not approve. “It bothers me that I couldn’t say for sure what happened to the ice bridge.”

“You’re tracking what the Queenston-Chippawa project is doing to the river? You’ve hooked up with those men you met at the Windsor way back?”

He places his hands flat on the table, spreads his fingers wide. “Bess, I’m a workingman, not the sort they’d ask to join their meetings.”

“What’s it for, then?”

“It’s just for me,” he says, tapping the notebook. “It’s the least I can do.”

He has never given me cause to doubt his word. I remind myself of it again and again, as I stitch the cuffs, as I kiss Jesse good night, as I pace the main floor with Francis in my arms and my lips against his downy hair.

Still, try as I might, the notebook is firmly lodged in my thoughts.

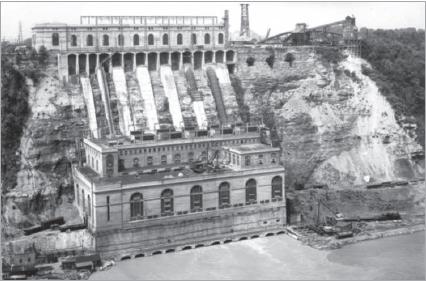

Queenston powerhouse under construction

Niagara Falls (Ontario) Public Library.

M

y coat is the same one I wore my final winter at Loretto, seven years ago. Twice I have raised the hemline, but there is nothing to be done about the worn cuffs and unfashionably nipped-in waist. For the past several years I have put off wearing it until the snow flies and then packed it away at the first sign of a thaw. As a result, I have spent many a cold morning shivering in a sweater, thinking I really should get down to the business of sewing myself a decent coat.

The coat I am making is narrow at the midcalf hem, broad through the waist, broader still through the hips. My first thought was velvet, but my practical side overruled and I am using a chestnut wool, as soft as cashmere but not nearly so dear. I had not quite made up my mind about the fabric for the collar and cuffs, but then Tom showed up with a typeset invitation, and I knew I would cut them from silk. If I was to wear the coat in the company of Premier Drury and Sir Adam Beck, it needed to be more than just warm.

Tom brought the invitation home from work on a Tuesday. Mr. Coulson had hand-delivered it to him that afternoon and said management thought the workers ought to be represented at the official opening of the Queenston powerhouse. “We’d like to include everyone,” he said to Tom, “but we can’t, and you’re the one we chose.”

I was delighted, but as Tom spread the invitation on the kitchen table, he said, “I’m not so sure.”

We get few invitations, certainly none as grand as the opening. There were to be speeches and pomp at the powerhouse, and then dinner and dancing in the ballroom of the Clifton House. I wanted to go. “I don’t think Mr. Coulson would understand if you declined,” I said. “It’s an honor to be picked.”

“I’d get mixed up about which fork to use.” I had explained it to him once, about starting with the utensil farthest from the plate, and he had shrugged his shoulders but never since made a mistake.

I raised my eyebrows, waiting for the truth.

“I’d feel like a phony, celebrating.”

I shifted my attention from the invitation to the saucer I was wiping dry. “You can accept or decline,” I said, aiming for nonchalance. “I won’t bother you about it either way.”

“You’ve got your heart set on going.”

“I wonder if Kit might be there with her husband.” Foolish or not, I was hopeful. It had been four years since Edward was killed, four years since I had seen the hostility in her gaze as she sat listening to the Niagara Falls Citizens Band. What is more, I came upon her in the street a short while ago and as usual she glanced away, but afterward I was almost certain of a moment’s hesitation before she did. Maybe enough time had passed.

“Let’s go,” he said. “I wouldn’t mind shaking Drury’s hand.” Since he became premier, Drury’s government has set out policies more sweeping than Ontario has ever seen for replanting forests and conserving water, and Tom very much approved. Still, I knew he had changed his mind on account of me.

I smiled. “I’ll finally get going on a new coat.”

“But I like your black one,” he said.

W

e drive along River Road in the Packard Mr. Coulson sent for us. The walk from Silvertown to the powerhouse is four and a half miles, and Tom regularly makes it on foot. But today the road is muddy and rutted, and the slush along the sides is at least six inches deep. Had we walked, we would have been spotted with dirt long before we arrived.

I made Tom’s overcoat as a Christmas gift the year before, and his suit has hardly been worn since our wedding day. The seams were ample, and I let out the trouser legs, also the waist of the jacket. His figure is as trim as ever, but a boxier sort of tailoring has come into style. I bought him a charcoal gray bowler with a small, speckled feather tucked into the band. He says he looks a fop in it, but he is wrong. Without trying, he is elegant. A quick shave and a comb through his hair. That is all it takes.

I had plenty of dresses to choose from and tried on one after another, remembering Isabel in the frock, heading off to a tea or in solemn procession at her graduation. When I got to my white concert dress, the memory was of me, hauling a trunk at Loretto, a section of skirt hiked up and tucked under the sash around my waist. A too long hemline is easy enough to fix, but women cast off the boning and lace collars and heavy skirts of the dresses ages ago, during the war, once they had learned to hoe potatoes and grind the noses of artillery shells.

There was no time for an entirely new frock, not if it was to have a bit of beadwork, but hidden away in my old trunk was the gown Isabel had meant to wear on her wedding day. Mother had put hours of work into beading the overskirt. I had never forgotten how lovely it was, with swirl upon swirl of seed pearls aligned end to end. It had always seemed such a waste.

So I am decked out in a midcalf-length chemise with an outer layer made from the overskirt of Isabel’s wedding gown. The frock was a cinch to make with the beading already done. The underlayer is pale pink, a silk georgette that feels luxurious against my skin, even more so when I think of the low whistle Tom let out as he saw me coming down the stairs. “I’ll have to make sure some rich fellow doesn’t run off with you,” he said. Because the dress easily stands on its own, I wear no jewelry other than Isabel’s aluminum bracelet, which is always clasped around my wrist.

Two more of my designs will debut tonight at the Clifton House. Mrs. Harriman chose a chic suit of sea green, sequined French serge, which Mrs. Coulson had insisted on inspecting when I made the mistake of mentioning it. She had traced a finger along a lapel and let out a satisfied

humph.

“Lovely, but I prefer my own,” she said. I decided against showing her my chemise. The beadwork is exceptional, and what is more she is curvaceous and the newer styles are more suited to women with the flat chest and narrow hips of a boy. At long last my figure is in style and my dress is perfect and Tom is handsome in his bowler and we are being driven in a Packard to the party of the year.

Before descending to the powerhouse at the river’s edge, Tom leads me over a series of planks to the rim of the gorge. Nine immense troughs have been at least partially gouged into the cliff face. Only two have been laid with the giant pipes through which the water will fall. Solid walls exist for the southern end of the screen house at the top of the gorge. The northern end is a hodgepodge of girders and scaffolding roughly marking out what has yet to be built. And at the base of the gorge the massive building meant to house the turbines and generators is as ramshackle as its counterpart above. “It hardly seems ready,” I say. I am not disappointed. The newspapers are correct; it will be another five years before all the generators are switched on, another five years of steady income for Tom.

Inside the powerhouse a crowd of men in bowlers and overcoats has gathered around a single enormous drum. There is no rope guarding it, yet the men maintain a gap of several feet between themselves and the gleaming generator, as though it were a shrine of sorts. I survey the crowd and find Leslie Scott. With my tendency to ask about him and to perk up my ears at the mention of his name, Tom has accused me of a schoolgirl crush. He chuckles as he says it, knowing full well I am only trying to glean what I can about Kit. She is not among the men at the powerhouse, which is hardly a surprise given it is four o’clock in the afternoon, not yet closing time for the businesses on Erie Avenue. The other wives, it seems, have mostly opted to stay home and make their entrances at the Clifton House, but I am glad I have come. There is excitement in the air, and Tom is holding my arm, and men nod in our direction, tentatively, as though their greetings might not be returned. Eventually one of the younger fellows comes over and introduces himself. “I’m Gerald Wolfrey,” he says, “and everyone knows you’re Tom Cole.” A colleague of Mr. Wolfrey wanders over and joins our small circle, then another and another. I had not expected it, but even the administrators and engineers charged with overseeing the workers digging the forebay and canal are deferential to my riverman.

It is easy to pick out Sir Adam Beck, with his high starched collar, regal profile, and tired eyes. Surely it has been a grueling few months. True, his dream is finally more than blueprints and excavated dirt, but his wife died several months ago, and the mudslinging is at an all-time high. The cost overruns are staggering, and his pat answers—conditions that could not have been foreseen, results that could not have been anticipated, wartime inflation, and shortages of men—no longer seem to suffice. His daughter is at his side, looking defiant and bored, as though she had accompanied her father against her will. I cannot yet see what she has on underneath, but my coat is not out of place alongside hers. Premier Drury’s suit is finely tailored, yet he looks every bit the farmer that he is, with his hair disheveled and his tie askew. Though he has been feuding with Beck in the newspapers, here they seem on friendly enough terms. I suppose it is only a premier’s job to scold when the books have been so sloppily kept and budgets so easily ignored.

Beck moves to the podium, clears his throat, waits for the crowd to hush. Then he begins:

Dona naturae pro populo sunt. The gifts of nature are for the people.

These are the words I spoke to Premier Whitney back in 1905, the very words with which the Hydro-Electric Power Commission was born, the very words with which the triumph of public power over private greed began. No longer would private industry be allowed to gouge manufacturers and citizens alike when a publicly owned company couldpro-vide cheaper electricity more efficiently. And surely those words, spoken to Premier Whitney in 1905, are as fitting as ever when considering the Queenston-Chippawa power project. At long last the bounty of Niagara Falls truly belongs to the people.

He goes on to thank the citizens of Ontario for having had the foresight to vote for the hydroelectric generating station five years ago. He says they have rid themselves of coal embargos and blackouts, and will pay less for electricity than anyone else in the world. With their source of abundant, cheap power, they will brighten their homes and places of work, and lighten the burden of farm and household chores, and more cost-efficiently run the factories and thus ensure more jobs and lower prices, placing more goods than ever before within reach of the common man. He thanks the administrators and the laborers, but most particularly he thanks the engineers, whom he says designed the most efficient power plant yet built.

While the others in the room applaud, Tom’s hands remain at his sides. I clap, tentatively, and wonder whether anyone else has noticed Sir Adam Beck’s adeptness at recognizing others while, at the same time, patting himself on the back. And when Premier Drury speaks, he is just as shrewd. Though the room is filled with businessmen, his words focus on the contributions of the laborers, the men who elected his party. He had correctly guessed there would be reporters scribbling. He had expected the flashes of the newspaper cameras in the crowd.

At the close of his speech, he flicks a switch, and a sign behind him reading

THE LARGEST HYDRO-ELECTRIC PLANT IN THE WORLD

lights up. The crowd applauds on cue, and I strain to pick out a sudden mechanical whir. But the room was loud with conversation when we arrived and is louder now with whoops and applause. I scrutinize the generator, looking for some hint of activity, but nothing has changed. Tom leans toward me and says into my ear, “It’s been on since last Wednesday.”

But the crowd is filing from the room, seemingly satisfied. “You’re sure

?

”

“The river dropped a half foot.”

T

he Clifton House ballroom is as I remember, with polished hardwood, Corinthian columns, giant ferns, and tasseled chandeliers, yet it seems grander, too, maybe because I am no longer used to opulence. The first strains of a fox-trot fill the room, confirming the thought I had just begun to think: I do not belong at the Clifton House, not anymore. The only steps I know are from before the war, learned at Loretto, practiced in the cozy little clubroom of the Gamma Kappa fraternity, one hand on Kit’s shoulder, the other on her waist. Fortunately the next song is an older one-step, and Tom’s hand is reassuring on my arm.

As we make our way around the ballroom, the odd flask is pulled from a pocket, tipped against the rim of a half-full glass. It seems a badge of honor, so grandly is the liquor offered, so openly is it poured. The Ontario Temperance Act has surely failed in the eyes of the legislators, unless, as some suggest, the laws are deliberately lax, meant only to shush the debate for a while. Whatever the case, just now I would like nothing more than a splash of rye whiskey in my ginger ale.

The women in the ballroom are glittering in beads and sequins, diamonds and pearls. I point out my handiwork to Tom, and he says it is the best in the room. Only Marion Beck’s dress is in the same league, and she is hiding it behind her crossly folded arms.