The Decadent Cookbook (2 page)

Read The Decadent Cookbook Online

Authors: Jerome Fletcher Alex Martin Medlar Lucan Durian Gray

The Decadent was, of course, too good to last. Despite a cult following, the business side never really held up, and Durian and Medlar were forced into ever more difficult choices between lowering their fastidious standards and raising their prices. The enmity of certain influential figures in the city didn’t help. After three years of struggling to break even, The Decadent closed. Durian and Medlar vanished - some said to New York, others to Tasmania, others to the Far East.

Nothing was heard of them for over a year. Then one day a parcel arrived at the Dedalus office in Sawtry, wrapped in grey recycled paper and roughly tied with brown string. It was postmarked Calcutta. A brief covering letter from Medlar Lucan - written in his usual purple ink - offered the contents for publication: it was a collection of Decadent recipes together with “notes and readings from our favourite authors”. The text was clearly a joint effort, with chapters in somewhat different styles by the two of them - Medlar inclining to the theoretical, the literary and the morbid, while Durian indulged his taste for the festive, the spectacular, the grotesque. What follows is the contents of that parcel - The Decadent Cookbook - all that remains of a wicked and exciting place.

J.F.

A.M.

HAPTER

1

INNER

WITH

C

ALIGULA

He built tall sailing-ships of cedarwood, their poops and sterns set with precious stones, their sails of many colours, and within them baths, great galleries, promenades, and dining-chambers of vast capacity, containing vines and apple-trees and many other fruits; and here he would sit feasting all day among choirs of musicians and melodious singers, and so sail along the coasts of Campania.

This was Caius, also known as Caligula - one of a series of emperors who turned Rome in the 1st century AD from a city of strait-laced farmers and soldiers into a seething cosmopolis of aesthetes, gluttons and perverts. Thanks to the fabulous wealth of the empire, the patricians of Rome had little need to work. Taking their lead from the emperor, they indulged in lust, cruelty, violence and sensuality on a daily basis. Despite two thousand years of atrocities (politely known as ‘history’) that have passed since then, their excesses still send shivers along the spine.

The Decadents of 19th-century France loved the unashamed filth and self-indulgence of it all - the sadism of Tiberius, the insanity of Caligula, the joky viciousness of Nero. They could all have come straight from the pages of Huysmans or Gautier. Edward Gibbon, in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, tells us that the emperor Heliogabalus ‘abandoned himself to the grossest pleasures with ungoverned fury, and soon found disgust and satiety in the midst of his enjoyments… To confound the order of seasons and climates, to sport with the passions and prejudices of his subjects, and to subvert every law of nature and decency, were in the number of his most delicious amusements’. In other words, he was the perfect Decadent.

Eating was one of the great pleasures of the age. Murder was its great vice. Claudius was killed by a dish of his favourite mushrooms laced with poison. Heliogabalus was stabbed by his own guards, his body dragged through the streets and thrown into the River Tiber. Caligula, before being murdered himself, liked a good dose of death mixed with his meals. He watched his grandmother’s funeral pyre burn from his dining-room, and had suspected criminals tortured and beheaded in front of him while he ate. His love of luxury was all-engulfing: he once gave dinner-guests an entire banquet made of gold, saying ‘a man must either be frugal or else Caesar’.

While the poor of Rome ate porridge, bruised olives and sheep’s lips, the rich feasted on the produce and spices of every known land - from Spain to China. Exotic foods, disguised foods, unlikely foods - these were all the rage. Sweet and sour sauces were an obsession. Heliogabalus ordered elephant trunk and roast camel from his kitchens, and spent a whole summer throwing parties where all the food was a single colour. The emperor Vitellius, who reigned from April to December 69 AD, was given a banquet by his brother where 2,000 of the most costly fish and 7,000 birds were served. His favourite dish, a monstrosity named ‘The Shield of Minerva, Guardian of the City’, included pheasants’ and peacocks’ brains, flamingoes’ tongues, livers of wrasse and the roes of moray eels.

The only surviving Roman cookbook was written by Apicius, who liked nothing better than clashing flavours and the use of rare, improbable beasts. Dormice, flamingoes, sea-urchins, cranes - practically everything that moved was slaughtered and cooked and served up as wittily and elegantly as possible. ‘They will not know what they are eating,’ he boasted - ‘anchovy stew without anchovies’! Apicius himself feasted his way through a huge fortune and then took poison rather than live a more modest life.

Dinner parties were a favourite entertainment. In fact they were the only entertainment (apart from sex in front of the slaves) available after dark. They began at the ninth hour (i.e. the ninth hour of daylight, between about 4 and 5 pm), usually after a workout at the baths. They were long and sometimes very wild. There was music, dancing, flirting, petting, and of course sex. Suetonius says that Mark Antony ‘took the wife of an ex-consul from her husband’s dining-room, right before his eyes, and led her into a bedroom; he brought her back to the dinner party with her ears glowing and her hair dishevelled.’ Caligula often did the same, adding a cynical commentary on the woman’s performance when he came back to the table.

PICIAN

N

IGHTS

Roman banquets are fun to do, but however hard you try the food is unlikely to be completely authentic. (It may also turn out insipid or even disgusting - read the passage from Smollett’s

Peregrine Pickle

as a warning). Apicius’s cookbook,

De Re Coquinaria,

is still available, but the ancient methods of cooking and presenting food are lost for ever. Apicius gives no idea of quantities or cooking times, and there’s even doubt about the identity of some ingredients.

Still, there’s nothing to stop you having a go, so here’s a simple checklist for a Do-It Yourself Dinner With Caligula:

•

Hire plenty of slaves for the evening

•

Serve three courses: gustatio (hors d’oeuvres)

fercula (entrées)

mensae secundae (dessert)

•

Lay on some entertainment (naughty friends, a good poet willing to read from his works, musicians, dancing girls from Cadiz)

•

Provide guests with couches, finger bowls, vomit buckets, and large linen napkins

•

Philosophy of the hour [declaimed by Trimalchio in Satyricon, as a slave dangled a silver skeleton before his guests]:

‘Look! Man is just a bag of bones.

He’s here, and gone tomorrow!

We’ll soon be like this fellow, so

let’s live! Let’s drown our sorrow!’

N

INVITATION

The poet Martial (c. 40-104 AD) issued dinner invitations to his friends in the form of verse ‘Epigrams’. Perfectionists who know the difference between a hexameter and a place to park the car might like to try it too. This is one of Martial’s best-known,

Cenabis bene:

You shall eat well, Julius Cerialis, at my house;

if you’ve nothing better to do, come round.

Your eighth hour routine is safe: we can bathe together:

you know the baths of Stephanus are just next door.

First I shall give you lettuce, useful for stirring the bowels,

and tender shoots of leek,

pickled young tuna larger than a lizard,

layered with eggs and leaves of rue;

more eggs will follow, cooked gently on a low flame,

with cheese from Velabrum Street

and olives that have felt the Picenum frosts.

That’s the first course. Are you curious about the rest?

I’ll lie, to make sure you come: fish, oysters, sow’s udders,

stuffed fowl and marsh birds

that not even Stella would serve at her rarest dinner.

One more promise: I shall recite nothing,

even if you read out your entire Gigantas

or your pastorals, which are nearly as good as immortal Virgil’s.

(Epigrams,

11.52)

Now it’s time for some food.

We begin with the

gustatio

or

ORS

D

’

OEUVRES

![]()

The classic opener was eggs, which Martial smuggled in with tuna and rue, and then again (he obviously loved them) with cheese and olives. Apicius recommends serving them boiled with a garnish of pepper, lovage, nuts, honey, vinegar and fish-pickle.

A more decadent alternative is sea-urchins. These should be cooked in fish-stock, olive oil, sweet wine and pepper - and are best enjoyed, says Apicius, ‘as one comes out of the bath.’

But enough of this coy stuff. Let’s go for broke here, with one of the greatest of all Roman delicacies:

LIRES

(R

OAST

D

ORMICE

)

![]()

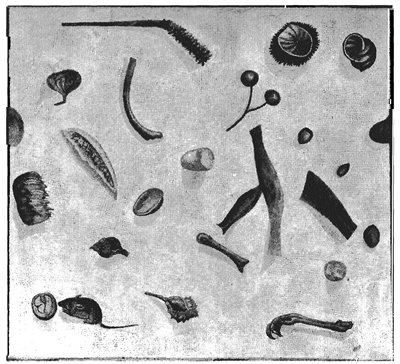

The dormouse, says Larousse, ‘is a small rodent that nests in the branches of trees and feeds on nuts, berries, and seeds. In ancient times it was considered to be a delicacy.’ The Romans bred them for the table in mud hutches and fed them on acorns through little holes. Unfortunately this is no longer done, so you must either find a very well-stocked butcher or take evening-classes in rodent-trapping. (Don’t be tempted to use a hunting rifle, because the recipe calls for whole dormice.) If all else fails, you could go to a pet shop where they don’t ask too many questions.

This is the recipe from Apicius:

Slit open and gut four dormice and stuff then with a mixture of minced pork and dormouse (all parts), pepper, nuts, stock, and laser (i.e. wild African fennel). Stitch up and roast on a tile or in a small clay oven.

Serve as they are, or as described in Satyricon, with honey and poppy-seeds.

If you can’t get dormice, ask your butcher to do you a few ounces of minced pork or veal and some calf’s brains; then, with squid from the fishmonger, you can cook this amphibian appetizer:

IC

FARCIES

EAM

SEPIAM

COCTAM

(S

QUID

STUFFED

WITH

BRAINS

)

![]()