The Diary of Lady Murasaki (2 page)

Read The Diary of Lady Murasaki Online

Authors: Murasaki Shikibu

Tags: #Classics, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

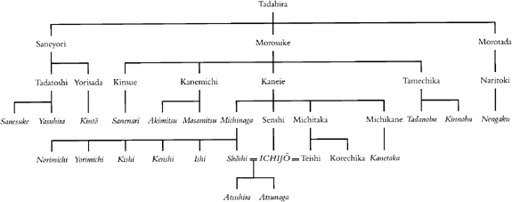

The story goes that Korechika, under the impression that retired Emperor Kazan was competing with him for the favours of a certain lady, surprised Kazan one night and started a scuffle in which the retired Emperor was actually winged by an arrow. Whether or not the whole scene had been engineered by Michinaga we do not know, but it provided him with the excuse he needed. Combined with an accusation that Korechika had been trying to place a curse on his uncle, it was enough to have him banished from the court for several months, and from this time on Michinaga proved virtually unassailable. In 999 he introduced his ten-year-old daughter Shōshi (988–1074) to court as Imperial Consort, and she quickly became promoted to Second Empress or

Chūgū

.

In the twelfth month of 1000, Teishi, who had been under considerable pressure since the disgrace of her brother Korechika, died in childbirth, and Shōshi’s position became secure. It was into her entourage that Murasaki, from a different and much less important branch of the Fujiwara, was to be introduced as a kind of companion-cumtutor. As we can tell from her diary and Sei Shōnagon’s

Makura no sōshi

(‘Pillow Book’), the women’s quarters in the Palace were organized around major consorts, and the quality of the cultural ‘salon’ that each woman could attract was a major factor in their constant rivalry. The real moment of success for Michinaga came when in 1008 Shōshi gave birth to a son, Prince Atsuhira (1008–36). This meant that if all went well Michinaga would be in full control of the next generation. This birth is the main event that Murasaki chronicles in such detail in her diary, hardly surprising in view of the supreme importance of the birth for the faction with which she now found herself involved. It was also a relief to Michinaga, given that the omens

had not been very propitious: Shōshi seems to have taken a full nine years to become pregnant.

Michinaga continued to gain influence throughout his career. In the end he could count himself as brother-in-law to two emperors (En’yū and Reizei), uncle to one (Sanjō), uncle and father-in-law to another (Ichijō), and grandfather to two more (Goichijō and Gosuzaku). There is evidence, however, that at this early stage Korechika continued to be a thorn in the flesh, for another scandal erupted in the first month of 1009 when it was ‘discovered’ that Korechika had arranged for a curse to be laid on Shōshi and the new prince. Korechika was banned from the court again, this time for six months.

It should be clear that women had an important role to play in the politics of the time. They were vital pawns, ‘borrowed wombs’ as the saying went, and, depending on their strength of character, might wield considerable influence. We know that they had certain rights, income and property that mark them off as being unusually privileged in comparison to women in later ages. Michinaga’s mother, for instance, seems to have been a power to be reckoned with, and his main wife Rinshi owned the Tsuchimikado mansion, where he spent so much of his time and which serves as the backdrop for most of the events in Murasaki’s diary.

It is much more difficult, however, to determine the true position of women in society at large. The testimony we have from the literature of the period, much of it written by women of a lesser class, draws a picture of women subject to the usual depredations of their menfolk, prey to the torments of jealousy, and condemned to live most of their sedentary lives hidden behind a wall of screens and blinds. Seldom were they known by their own names; they existed rather in the shadow of titles held by brothers and fathers, borrowed labels. Secondary wives of major figures probably had the worst position, as we can tell from a reading of the

Kagerō nikki

(‘Gossamer Years’). The author of this particular autobiographical work was trapped at home, at the mercy of her husband’s slightest whim; he had official business and other love affairs to keep him busy. For women like this there were only two escapes – to enter service at court, or to seek solace in

Main members of the Fujiwara clan

[

Names mentioned in the diary are in italics

]

religion. Murasaki seems to have decided on the first option, which probably came in the form of a request to join Shōshi’s entourage; but even so, her diary tells us that life at court was not all it was cracked up to be. Amid a certain magnificence, she also found drunkenness, frivolity, back-biting, and a general sense of life being wasted. We should not, of course, be surprised by any of this. What is truly remarkable is that a number of court women were able to write about their situation in such a fashion that their predicament speaks directly to us today, across barriers of time and place. It is perhaps salutary to remind ourselves that as Murasaki was writing in such exquisite detail of court ceremonial on the one hand and personal feelings on the other, we in England had still full sixty years to go to the Norman Conquest.

LANGUAGE AND STYLE

The impact of Chinese civilization was felt everywhere in ninth-century Japan but perhaps nowhere more strongly than in matters of language. The Japanese had no writing system of their own prior to their contact with China, so literature itself was a concept learned from Chinese example. By Murasaki’s time, written Chinese had been the main vehicle for the bureaucracy for some centuries. By the mid ninth century a syllabary had been developed from a set of Chinese characters used solely for their phonetic value, and this finally led to the growth of written Japanese. In the early stages this was restricted to private correspondence and native poetry. We know from a famous passage in Murasaki’s diary that it was still considered unbecoming for a woman to know Chinese, a useful fiction if the intention was to keep the language of bureaucracy in male hands. What this did, however, was to encourage the women to develop written Japanese for their own ends, and in particular for self-expression. So it is that Heian Japan offers us some of the earliest examples of an attempt by women to define the self in textual terms.

Part of the importance of women such as Murasaki is, therefore, their role in the development of Japanese prose. It is sometimes forgotten how difficult a process it is to forge a flexible written style out of a language that has only previously existed in a spoken form. Spoken

language assumes another immediate presence and hence can leave things unsaid. Gestures, eye contact, shared experiences and particular relationships all provide a background which allows speech to be at times fragmentary, allusive and even ungrammatical. Written language on the other hand must assume an immediate absence. In order for communication to take place the writer must develop strategies to overcome this absence, this gap between the producer and receiver of the message. The formidable difficulties that most of these texts still present to the modern reader are in large measure attributable not to obscure references (although there are some, of course), nor to deliberate archaisms or what we commonly refer to as ‘flowery language’, but rather to the fact that the prose has still not entirely managed to break free from its spoken origins.

Murasaki’s diary can be read as a kind of testing ground for different styles – three styles, to be exact: first, the kind of factual record one might expect from someone practising to be a chronicler of the time; second, the kind of self-analytical reflection that one might expect of a writer of fiction; and third, a letter to a friend or relative.

We may find the record sections of the diary somewhat tedious, but it is important to remember that such a style and such a subject was still fairly new; records were usually written by men in Sino-Japanese, a hybrid form of writing that was, in a sense, designed for this specific purpose and was certainly far removed from the spoken form of either language. Murasaki was by no means the first to attempt this kind of impersonal, decentred writing in Japanese, but there can be no doubt that it was still in the process of being formed. It was something that had to be practised, something that an aspiring writer in her own native language would have to be able to handle without difficulty. It thus holds an interest and a stylistic importance that is difficult for us to re-create today, especially in translation.

The second style is, if anything, even more important, because without it Murasaki’s work would not have the kind of strong appeal it does. Sino-Japanese was so artificial and inflexible a medium that it is difficult to imagine a Japanese of the time being able to use it to express innermost thoughts. Perhaps Fujiwara no Sanesuke (957–1046) in his diary

Shōyūki

comes closest, but still the gap between what he

finds himself revealing and what Murasaki can reveal is vast. In this sense, then, Murasaki’s diary was another major step, not only for women, but for the language as a whole.

Lastly, whether or not one believes the ‘letter’ section of the diary to be a real letter or a fictional one, it shows the author dealing with yet another problem: how to maintain a fairly recently developed literary style in a context which closely approached the spoken. This is perhaps the most difficult of the three experiments. Near the end of the letter there are in fact signs that the style is breaking down, degenerating into precisely those disjointed rhythms that are characteristic of speech.

POETRY

Here and there in the diary, the reader will come across the odd poem or exchange of poems. To an English reader they may seem cryptic in the extreme and somewhat puzzling. A Japanese poem appears at first sight to be little more than a statement thirty-one syllables long. There is no rhyme and no word stress to form the basis of a prosody, so the basic rhythm is provided by an alternating current of 5/7 or 7/5 syllables. The form that we find in the diary, so-called

tanka

or ‘short poems’, is made up of five such measures: 5/7/5/7/7. There is often a caesura before the final 7/7 but not always. These measures are phrases but not really lines as the term is usually understood, and most Japanese poetry is in fact found written in a single vertical line. It is for this reason that the usual poetic techniques in English cannot be brought into play when attempting a translation. Add to this the fact that much use is made of various kinds of wordplay, intertextual reference, inversion and the like, and it should be obvious why translation is an extremely hazardous affair. Japanese poetry may be short but the result is often a complex weave of words: the texture is the poem.

Poems as short as this do not survive well on their own. Clever statements usually call for some kind of response, otherwise they simply hang there in mid-air. Hardly surprising then to find that poems like these often occur in pairs, their natural habitat being dialogue. They are thus ideally suited to flirtatious banter, used as one of

the most important weapons in what we might call a Japanese version of the ‘battle of the sexes’. But that is not all. It would appear that the ability to toss off an appropriate poem on any occasion was a

sine qua non

of court life. The number of good poets was probably as limited as it always is, and much of the poetry was certainly mediocre, but it is a commonplace of court societies everywhere that the most ordinary and obvious of activities becomes wrapped in ritual and technique so that essential difference may be preserved and highlighted. Legitimacy, and indeed

raison d’être

, lies within such difference, and what could be more exclusive than the habit of conversing in pairs of cryptic 31-syllable statements? It amounted to a special, artificial dialect. The problem with artificiality of this kind, however, is that it becomes extremely difficult to identify a personal voice behind the strict conventions that grow up around such poetry. Given that much of it was, in any case, meant to be indirect, allusive, and ironic in tone, perhaps it is best to assume that to look for a personal voice is a fool’s errand.

RELIGIOUS BACKGROUND

Although it is extremely doubtful whether Murasaki would have had a concept of ‘religion’ as a definable area of human experience, she would have certainly recognized the difference between sacred and profane. She would not, however, have seen ‘Shintō’ and Buddhism as being traditions in any way commensurate. Indeed they managed to coexist precisely because they fulfilled very different needs and so came into conflict but rarely. The use of a term such as ‘Shintō’ (‘Way of the gods’) in such a context is in fact anachronistic, because during this period it was neither an organized religion nor a recognizable ‘way’ to be followed by an individual. The attempt to create a doctrine and so to provide a viable alternative to Buddhism came much later in Japanese history. Shintō was not an intellectual system in any sense. It was rather the practice of certain rituals connected with fertility, avoidance of pollution, and pacification of the spirits of a myriad gods. At the individual level this was not far removed from simple animism, an activity governed by superstition and the need to pacify whatever was unknown, unseen and dangerous. At the level of court

and state, however, we find something more formalized, a collection of cults connected to aristocratic families and centred on certain important sites and shrines. Although there did exist formal institutional links between these shrines, in the sense that the government made attempts to put them under some measure of bureaucratic control, they were essentially discrete cults; we cannot, therefore, treat ‘Shintō’ as a true system. The Fujiwara clan, for example, had its cult centre with its shrine at Kasuga in the Yamato region. This was not linked in any meaningful sense to the shrines at Ise, where the cult centre of the Imperial Family was situated. The Imperial Family sought legitimacy for its rule via the foundation myths propagated in the

Kojiki

(‘Record of ancient matters’) of 712, but from a Western perspective it is important to understand that this text was mytho-historical in nature, not sacred in the sense of having been ‘revealed’. It was not itself of divine origin. It merely explained the origins of Japan and its gods and justified the rule of the Emperor by the simple expedient of linking him directly to these gods. Few could have questioned the story it told; but by the same token it was nothing more than a record of the country’s past. The concept of a sacred text does not exist apart from prayers and incantations.