The Diary of Lady Murasaki (3 page)

Read The Diary of Lady Murasaki Online

Authors: Murasaki Shikibu

Tags: #Classics, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Cult Shintō, if we can call it that without suggesting too much of a system, was therefore linked to matters of public, state and clan ritual rather than private concerns. Of the many centres in Japan, it was those at Ise and at Kamo, just north of the capital, that loomed largest in the consciousness of women such as Murasaki. Both these shrines were central to the legitimacy of the imperial house. There were, of course, others; but these were the most prominent. Ise was by the far the oldest but was also far removed from the capital, linked only by the presence there of the High Priestess of the Ise Shrines, usually a young girl of imperial lineage sent as imperial representative. Few courtiers would have ever been to Ise and most would have had only a very hazy idea of where it lay. Kamo, however, was just north of the capital and within fairly easy access. The institution of High Priestess of the Kamo Shrines was in fact only a fairly recent one, begun in the reign of Emperor Saga in 810. The capital had moved from Nara in 794 and the Imperial Family must have decided that there was a need to create

a shrine in the vicinity of the new city. As was the case with Ise, a young girl was chosen to represent the Emperor at the shrine, to ensure the correct rituals were carried out and to maintain ritual purity. Although the intention had been to choose a new girl for every new reign, by Murasaki’s time one person, Senshi (964–1035), a daughter of Emperor Murakami, had become a permanent occupant of this post. She held it continuously from 975–1031.

We know from Murasaki’s diary, as well as other sources, that Princess Senshi had a formidable reputation as a poet and that she ‘held court’ at her home near the Kamo shrines. Although Murasaki betrays a certain prickliness at the way this reputation was spread abroad, she nevertheless recognizes Senshi’s worth as the leader of a kind of rival literary coterie. We therefore have the somewhat odd spectacle of someone who was supposed to be living in purity and seclusion holding court to visitors of a distinctly secular cast, male as well as female. Perhaps it was for this reason that Sei Shōnagon in her

Pillow Book

considered Kamo to be ‘deep in bad karma’.

It happens that not only is Princess Senshi central to one of the main passages in Murasaki’s diary but also she provides a good example of the kind of tensions that could exist between Cult Shintō and Buddhism. These traditions are normally thought of as being in total harmony in this period, fulfilling complementary roles. This may well have been the case in many shrine-temple complexes where gods were simply seen as the other side of the Buddhist coin, where every shrine had some sort of Buddhist temple and every temple its protective shrine, but in the restricted world of a place like the Kamo shrines and at Ise, the demands of the two traditions certainly did clash. We know from the collection of Senshi’s poetry

Hosshin wakashū

(‘Collection of poems for the awakening of faith’) that she was constantly torn between the demands of ritual purity, which forced her to avoid contact with all forms of pollution including Buddhism, and her own deeply felt need to find salvation. She was a firm believer in the message of the

Lotus Sūtra

and in Amida as saviour.

Cult Shintō, then, seems tohave offered no personal creed, not even for one of its High Priestesses. The impression we get from the literature of the time is that these shrines were not places where an individual

would go to pray. Access was usually strictly limited and in most cases remained the prerogative of priests alone. They were sacred sites, where the gods revealed their presence. Once or twice a year public rituals were held, which often took the form of festivals, but the shrines themselves were remote, places of ritual purity whose careful maintenance was essential for natural good order and to ensure future prosperity. It is clear from the case of Princess Senshi that only Buddhism could provide the kind of personal consolation that she needed.

1

So what of Buddhism at this time? By the tenth century, this import from India and China was firmly entrenched in Japanese court society. It will be noticed, for example, that the majority of the rituals that surround the events in the diary are Buddhist. But there are many forms of Buddhism and the ritual side that we see here is largely tantric in nature. The priests mentioned in the text came from the two major Heian sects, Tendai and Shingon, both of which wielded considerable power. To someone like Murasaki, this is superb, awe-inspiring spectacle with the chanting of sūtras, the burning of incense and quite violent rites of exorcism. It is this kind of ritualized Buddhism that became linked to the native cults via a series of ‘identifications’ of certain gods with certain Buddhas.

We can tell from Murasaki’s diary, however, that there was another kind of Buddhism, the worship of Amida (Amitābha) Buddha. This seemed to answer a more personal need for salvation. Princess Senshi felt the same urge and, despite the tremendous obstacles in her way, chose the same path. Murasaki herself must have been well aware that the Buddhist rituals she saw at court and the path of personal salvation through the worship of Amida were at root connected, but nevertheless one senses a divide. Although we have not yet reached the stage when Amidism becomes to all intents and purposes a monotheistic religion, there can be no doubt that it, and not tantrism, provided the major source of personal solace for these women.

ARCHITECTURE

Much of the ‘vagueness’ for which Heian literature is supposedly famous stems in large part from a natural assumption of prior knowledge. Take, for example, the word ‘palace’ as used by Murasaki in this diary. One might expect this to refer to the imposing structure which dominates all formalized maps of the capital, but in fact it refers to a mansion that Emperor Ichijō was forced to use as a substitute because the buildings formally designated as his proper palace had burned down. Ichijō had already been forced to live in a substitute residence twice before, but this was to be the last and the longest of his absences. The main Imperial Palace burned down on Kankō 2 (1005).11.15. He then moved to a number of different buildings before finally settling at the Ichijō mansion on Kankō 3 (1006).3.4. He was to stay here until his abdication and death in 1011, with the exception of the period from Kankō 6 (1009).10.4 to Kankō 7 (1010).11.28, when the Ichijō mansion itself burned down and he had to move to the Biwa mansion. It is this mansion that in fact forms the backdrop for the very last section of Murasaki’s diary.

It is useful to remember that for a good portion of his reign, then, Ichijō had to rely mainly on Fujiwara largesse and did not have a proper home base for his activities. The Ichijō mansion was very close to the main palace grounds, near the north-east corner, and belonged to his mother Senshi. His posthumous name came from his association with this mansion, and he may have felt fairly much at home there; but the fact remains that it was a Fujiwara possession. The move to the Biwa mansion – so named after the loquat trees (

biwa

) in the gardens – must have been even more restricting; this residence was much further to the east in what can only be called the ‘Fujiwara quarter’ of the city, and it had come into Michinaga’s possession in 1002. During this period, then, the Emperor was living under his father-in-law’s roof.

The diary opens with an autumn scene at the Tsuchimikado mansion. This belonged to Michinaga’s wife Rinshi, but Michinaga himself started to use it as his principal residence from around 991. It did not become his property as such until much later, when in 1016–17 he paid for its reconstruction after yet another disastrous fire. It occupied

a large area (two ‘blocks’, 2493 × 1187 metres) in the far north-east corner of the capital. It was here that Michinaga’s daughter, Empress Shōshi, came to give birth. Partly this was to avoid the strict taboo on the shedding of blood in the precincts of the Imperial Palace (or what stood for them), but it must have also presented Michinaga with a marvellous opportunity to show off his wealth and power. Murasaki’s description of the occasion of the Imperial visit to the mansion to see Shoōshi and the new baby, when hewas hardly given any time together with her (‘The Emperor went in to see Her Majesty, but it was not long before there were shouts that it was getting late and that the palanquin was ready to leave’), shows just how much Ichijō was at the mercy of protocol and bereft of any say in his own activities.

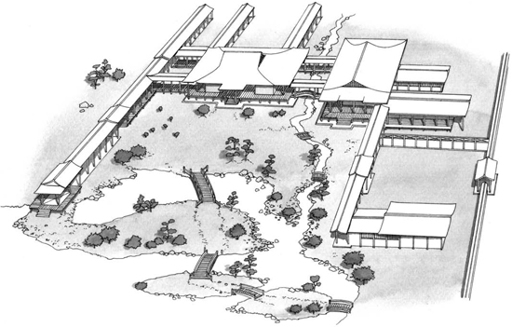

Domestic architecture of the period was very distinctive, and it is important for the reader of Murasaki’s diary to be aware of its main features. To understand a particular action, or indeed a particular emotional reaction, one must know where people are sitting, what the building looks like, and what the people are looking at. The mansions themselves were only rarely more than one storey high but they covered a large area; a series of rectangular buildings linked by covered walkways, the central structure being by far the largest. The whole residence would be enclosed by walls with entrance gates on at least three sides. The main buildings would lie to the north with wings east and west extending out into the gardens, which lay to the south. All construction was of wood, with bark rather than tiled roofs. The base was raised on thick stilts about one or two feet high to provide as much airflow as possible during the semi-tropical summer months and because of the generally damp atmosphere of Japan. The architecture was open, numerous pillars supporting a large expanse of roof on elaborate trusses. The roof line would sweep down well beyond the pillars so forming an extra protected area skirting the building. Outside that there would be a veranda. Inner space was divided from outer sometimes by wooden walls but for the most part by a series of removable screens. These were designed so that the top half could be swung up; the bottom half needed more effort because it had to be removed in its entirety. Behind this there would be a layer of blinds and perhaps curtains. The core characteristic of these buildings was that the

Representation of a typical Heian mansion (after

Nihon emakimono zenshū

, vol. 12)

boundary between outside and inside was fluid in the extreme, with a design of utmost flexibility. The one drawback was of course their vulnerability to the inclement weather. They must have been unbearably cold in winter with no protection from the wind and little to warm one but a small brazier. It is hardly surprising that these buildings burned down with depressing regularity.

The lack of a sense of boundary was reflected inside as well, where a ‘room’ might well consist of nothing more than a ‘tent’ of curtains. At busy times one’s room might even have to be set up in the corridor that skirted round the outside. Privacy in such an environment was impossible, especially as the space above the ‘room’ divisions must have been open to the roof, with all that meant for overhearing conversations. The floors were usually bare wood with the occasional mat. The modern Japanese

tatami

mat that covers the whole floor and ‘gives’ a little had not yet been invented. Furniture was minimal. By and large the interior of this large space must have been extremely dark, and the inhabitants for at least half the year had to wear many layers of clothing to keep warm. It is these clothes that became the subject of near-fetishistic concern with the ladies-in-waiting. Most of the women spent most of the time either sitting or kneeling on the floor, and their bed would be a thin mat simply rolled out. A man standing outside in the garden looking in, therefore, would have had the railings of the veranda at about mid-height and his eyes would have been roughly level with the skirts of the women inside.

It is clear from Murasaki’s diary that she was extremely interested in her surroundings. This may partly be a false impression produced by a desire to describe positions accurately for the sake of the record, but even so one cannot help being struck by the degree to which the author is aware of position and placing within this large residence. There are general links here, of course, to a cultural obsession with hierarchy and status, but it is of interest that the cardinal points of the compass are very clear in the mind of the writer. They help give a specificity to the descriptions. From one angle the fact that we need plans and drawings to understand what is going on in certain sections of the diary can be seen as a criticism. From another angle, however, it is truly remarkable that we can in fact create accurate plans on the

basis of her record. If her aim was to practise building up a word-picture of a historical event in all its concreteness, the experiment must be judged a brilliant success.

DRESS

No one could fail to remark on the extent to which Murasaki concentrated on her descriptions of dress. The detail here too is at times almost suffocating. Clearly, concerns with colour combinations and types of fabric and weave were close to a fetish in court circles. This went beyond the usual concern with what might or might not be allowed: taste in clothes was obviously a major indicator of character and style, one of the ways in which a lady-in-waiting could make her mark and show her individuality. It is again difficult to gauge whether such detail was present simply because Murasaki wished to produce as close a record of an event as possible or whether she herself was obsessed with such details for other reasons. Be that as it may, it is important to have as clear a picture as possible as to what these dresses looked like. As the illustration indicates, we should not try to visualize the modern kimono with its tight, wide belt held high over the breasts. The clothing worn by Heian court women was much looser, much longer and in many more layers. There was a basic white undergarment and a pair of long trouser-skirts,

nagabakama

, usually red, which formed the basis for the following: