The Donut Diaries (15 page)

Authors: Dermot Milligan

The searchlight swept over the field at 12.15 a.m., but I’d anticipated it and dragged

Renfrew

down onto the ground. The dogs would be harder to avoid, but I planned to cross that sausage dog when I came to it.

In a few minutes we came to the gap in the fence marked on Renfrew’s map. There was a sign:

What did that mean? Minefield? No, that would be against the Geneva Convention, surely? It must have just been an empty warning.

The gap in the fence was actually more of a corridor, or a tunnel, as the wire continued on

each

side. I was about to lead the way through when Renfrew put his hand on my arm. He pointed to a leaf floating down from one of the trees just outside the fence. For a second it was caught in a red beam.

‘Motion sensor lasers,’ said Renfrew, ‘set into the fence post.’

For a second I imagined a laser cutting me completely in half, and my poor chubby legs running around for a while before they realized what had happened, and fell over.

‘I thought this was all a bit too easy,’ I said.

I also wondered what could be so important about Hut Nineteen that it needed this sort of security. My half-starved brain thought for a second or two that perhaps this was where they kept the donuts, and I felt my mouth fill with drool. But no, whatever lay at the heart of this

mystery

, it was unlikely to be a ring of deep-fried dough, dusted with icing sugar, still warm . . .

Focus. I had to focus.

I had no idea how many lasers there were, cutting across the corridor. There was a faint chance that there might just be this first one, but the evidence of almost every computer game I’d ever played suggested that there would be loads of them, zigzagging across the path like a cat’s cradle. The first beam – the only one I had seen – was perhaps half a metre up from the ground. Too high for most fat kids to jump, and too low for them to crawl under, without a fat butt-cheek cutting the beam and either setting off the alarm (most likely) or getting sliced off by the high-powered laser (less likely, as this wasn’t a game, but real life).

Too low for most fat kids, but . . . I still hadn’t

eaten

any of the weird meat they’d been serving up, so I’d been ‘living’ on a diet of gruel and carrots for over a week now. I felt at the waistband of my tracksuit. It was loose. I’d lost an awful lot of puppy fat since I’d been here. Could I, perhaps, fit under the beam?

‘OK, Renfrew,’ I said. ‘Let’s do this.’

I threw myself down, and began to crawl and squirm on my belly. Crawling on your belly is one of those things that looks fairly easy, and is in fact fairly easy for the first couple of metres. It then goes from being uncomfortable, to very, very uncomfortable, to utterly, agonizingly hard. Plus, there was that whole getting-my-bum-lasered-off thing, which I knew probably wouldn’t happen. But then eleven days ago I’d have said that everything that’s happened to me over the past ten days could never happen, so you never

know

. And if there really were laser beams, could I rule out landmines? Maybe left over from the war when Camp Fatso was a prison camp? I wondered, as I crawled, if it would be better to be blown sky-high by a landmine or have one of my buttocks sliced off by the laser. True, with the landmine, I’d be pretty much 100 per cent dead, which was a very poor outcome by anyone’s reckoning. But having a buttock sliced off would be pretty embarrassing too. How would I ride a bike? You need the full set of buttocks for that, or you’d just slide off, to general ridicule.

Well, either there weren’t any lasers or we successfully scrunched beneath them, for we came through the tunnel with all our buttocks intact.

‘You OK?’ I asked Renfrew as we brushed the grass and leaves off our clothes.

‘Fine. Rather enjoying all this, actually.’

I could sort of see how this might be fun for Renfrew. His parents thought that playing the violin and doing maths puzzles counted as entertainment, so crawling through the mud on your belly after a day of eating gruel and making Japanese grunting sounds was probably quite enjoyable.

Renfrew checked his map again and pointed. ‘It should be just beyond those trees.’

We followed a little path through the screen of scrubby trees, and there, looming up before us in the moonlight, was Hut Nineteen. And now I didn’t have to concentrate on not being lasered, I noticed something else: the smell. It was deep and rich and truly terrible, like a lasagne made from a tramp’s underpants and dog sick.

I couldn’t see anyone around, although I did hear the distant yapping of a sausage dog.

I hurried to the hut, through the growing stench. Four wooden steps led up to the door. I tugged at the handle.

‘Locked!’

Maybe we should have taken that as our cue to get the heck out of there. But now we had come this far, we had to go on.

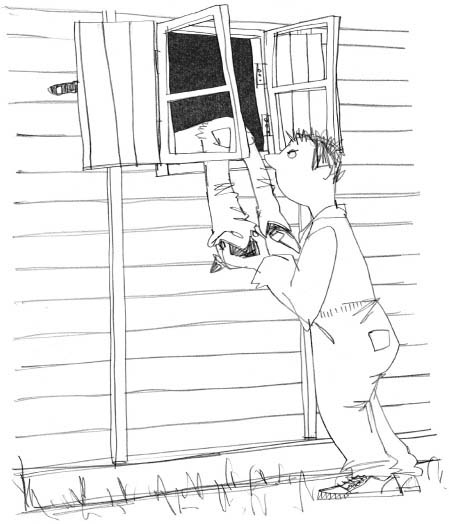

‘There’s a window,’ said Renfrew.

It was shut, but the wood was ancient and rotten, and a shove with the palm of my hand forced it open.

‘Up you go,’ I said to Renfrew.

‘Why me?’

‘Because I’m in charge of this mission, plus that window frame looks a bit rotten, and it might break if I step on it.’

I also suspected that even in my new, slightly thinner form, I was still too fat to squeeze through the window. Renfrew, on the other hand, could have been made for squeezing through small spaces. I gave him a boost up.

‘When you’re in you can open the door for me from the inside.’

He stuck his head through the window, then drew it back, like someone snatching their hand from a flame.

‘Reeks,’ he said. ‘And there’s something alive in there. I can hear it . . .’

‘Just get on with it, Renfrew,’ I said rather sternly, and gave him a helpful shove. He half fell through, then scurried round to the door. He opened it, and a wave of stench flowed out, carrying Renfrew with it. His face was tight with terror.

‘I’m not going back in,’ he said, trembling. ‘It’s . . . it’s horrible.’

‘OK,’ I sighed. ‘You wait here then. You can be the lookout.’

I took J-Man’s torch from my pocket, held my breath and walked into Hut Nineteen.

It was like walking into hell itself, such was the stench. It clung to me, thick as Marmite. There was a noise. A restless noise. A shuffling. And perhaps, somewhere, a hiss. Or a sigh. I sensed that the hut was full, but full of what?

I flicked the torch on, and still I could not understand what its beam revealed. Boxes. No, not boxes. Cages. Small cages, stacked from the floor almost to the ceiling, filling every available space.

I moved closer to one of the stacks, trembling. I shone the light through the chicken wire. And there, cowering in the corner of the cage, I saw, not a badge, but . . .

‘A badger?’ J-Man’s eyes were wide with

disbelief

. ‘You are one crazy dude. Ain’t no badgers in cages. Why’d anyone want to do a damn fool thing like that?’

It was the next morning, i.e. today. We were trudging through the woods on our way to dig worms.

‘Yes – you see, Tamara didn’t say “badges” but “badgers”. I figured it all out. The meat. The stuff they give you with the gruel. It’s badger. Has to be. And those carcasses hanging in the cooler? Badger for sure. And you know what was in their feeding trays? Worms. Yeah, worms. That’s why we spend our days out in these woods, digging. We’re all part of this.’

‘Boy, have you been reading books again, or what? Nobody eat badger. Nobody keep badgers in cages. I say you fell asleep in the john and dreamed it all up.’

‘Both of us?’ said Renfrew.

‘Yeah, well, you’re a new kid, and what new kids say don’t count.’

‘I know what I saw, J-Man. And I know it’s not right. And I want to break them loose.’

‘And how you gonna do that, even if you

is

right? You couldn’t even get your own self out of here. You think you can stroll out through them gates with two hundred badgers down your pants? You got a bit more room down there than when you first came here, but not enough for that kind of payload.’

‘There’s a tunnel. Dug by the Italians in the war. Renfrew found old letters from the prisoners in an archive on the internet. Prisoners who escaped.’

‘Really? And where that tunnel be?’

‘Ah, well, I don’t know, exactly.’

‘That ain’t much use, is it?’

‘There must be a way of finding it. Somehow we’ve got to get those badgers out of there. And we have to do it by Friday. There was a schedule pinned to the inside of the door of Hut Nineteen. Feeding times, that sort of thing. And then, for Friday evening, there was a black cross. It means that’s when they’re going to kill them. I know it. And you’ve got to help me.’

J-Man did his now familiar slow head-shake, and then he started breaking up the ground with his pick. After a while he said to me, ‘Lardies might know if there’s a tunnel. If you want I can fix for you to see the boy Hercule Paine. I don’t recommend it, no sir. But if that’s what you want, then be it on your own head.’

‘You can do that?’ I said, my hopes putting in a little spurt. ‘I thought he hated you,

and

you hated him?’

‘That about the size of it. But I still got some influence. I ain’t happy about it, but I see what I can do. This gonna cost you. This gonna cost me. You make a pact with the devil, the only coin he care about is your soul.’

And then J-Man hit the turf with his pick so hard I thought he was going to open up a crack to the molten core of the earth itself.

The message came back through J-Man, though he couldn’t even bear to look me in the eye as he told me.

‘You get yourself to Hut One after dinner.’

The other guys heard what he said.

‘You shouldn’t go there,’ rumbled Igor. ‘Only trouble will come. You should stay and play chess with me.’

‘Yeah,’ said Flo. ‘You shouldn’t see the bad boys. The bad boys are bad. You should stay with the goodies.’

‘Hello, old chap, delighted to make your acquaintance,’ said Dong, but he got his message across pretty well too.

‘Sorry, guys. I’ve got to do this.’

‘Why?’ said Igor. ‘I don’t understand. Why are you going to see the Lardies? Are you joining them?’

‘Nah, nothing like that. I can’t tell you any more. It might get you into trouble. Let’s just say that it’s something I have to do. You’ve just got to look after Renfrew for me while I’m gone.’

‘Sure thing.’

I didn’t really need to ask. Renfrew had become a sort of pet to the Hut Four guys.

And so it was that I found myself knocking on the door of Hut One after dinner this evening.

The door opened, and there in front of me was the one they called Demetrius the Destroyer. He had a face like a half-eaten pork pie. The word was that he’d once bitten the head off one of the sausage dogs for making the mistake of yapping at him. I didn’t know if that was really true, but I wasn’t going to put it to the test by yapping.

‘Boss, the Donut kid’s here,’ he said out of the side of his mouth, without taking his eyes off me.

‘Spread ’em,’ he said.

‘What?’

‘Against the wall. I gotta frisk you.’

So I put my hands against the wall and let the big lummox pat me down. He did it with all the gentleness of someone trying to beat a monkey to death.