The Dream Killer of Paris (3 page)

Read The Dream Killer of Paris Online

Authors: Fabrice Bourland

‘How do you intend to proceed, Superintendent?’ I asked, realising that I was more intrigued by this story than I had expected.

‘Firstly, by paying a visit to Château B—. I have an appointment with the examining magistrate appointed by the Versailles public prosecutor early tomorrow afternoon. Just between you and me, until yesterday the Justice Minister wanted nothing to do with the death of the Marquis de Brindillac, the public prosecutor couldn’t care less either and the general public likewise. Now, everyone wants to stick their oar in.’

With a gulp Fourier swallowed the rest of his Burgundy. Wiping a drop of wine from his moustache, he declared in a detached tone: ‘I say! I’ve just had a thought. Since you’re on holiday in our beautiful city, why don’t you come to the château with me tomorrow? You can share your thoughts with me. You can make room in your schedule, surely, to give up a day to shed some light on this case.’

I couldn’t help smiling. The trap was a little obvious but it had worked perfectly. As Fourier had said, it was certainly mysterious and I also found it rather gratifying, that at the age of twenty-five, my services were required by one of Paris’s leading detectives. Besides, I’d promised James that I wouldn’t let a case slip through my fingers if it presented itself and that I’d alert him as soon as possible. And, in return, Fourier could help me gain access to certain archives for my investigation into Nerval’s death.

‘Yes, yes,’ I said. ‘But I warn you, tomorrow evening I will return to 1855.’

‘Glad to hear it!’ retorted Fourier. ‘Let’s meet tomorrow at half past eleven at the Gare d’Orsay.’

‘What? Aren’t we going by car?’

‘Our vehicle has been at the garage for the last two weeks. The Sûreté Nationale might have been allocated more funds but it’s hard to tell sometimes.’

We had spent longer than expected chatting in the café. Outside, night had almost fallen.

‘I must go!’ exclaimed Fourier, looking at his watch. ‘As we speak, the head of the Sûreté and the Préfet de Police are meeting the Interior Minister, Monsieur Sarraut. I imagine he is going to demand close collaboration between our two forces.’

He threw some coins down on the table. As he shook my hand, he suddenly looked at me curiously.

‘By the way, what is this investigation which means I have the pleasure of your company here?’

‘The death of Gérard de Nerval.’

‘What? The poet?’

‘The very same.’

‘But wasn’t it suicide?’

‘That’s exactly what I’d like to know for certain!’

From the brasserie, I headed towards the Seine. My expedition to Quai de la Rapée was no longer relevant. Crossing

Pont-au

-Change, I leant over the stone parapet for a moment and contemplated a passing

bateau-mouche

with its blinding headlights, which was carrying a handful of tourists awed by the splendours of Paris. The season was over but the fine weather had prolonged the euphoric feeling of summer. Something told me that things were going to take a turn for the worse though. Was it the night itself, which was getting darker by the minute on the horizon, far from the lights of the Seine? Was it the icy shiver that ran down my spine despite the relatively balmy air? Was it the silty black water swirling in the middle of the river and which continued churning long after the boat had passed as if some obscure, ancient underground force was extending its empire to the world’s surface?

I continued on my way via Boulevard Saint-Germain and Quai Saint-Bernard up to the Jardin des Plantes. As I passed a post office, I stopped to send James a telegram.

STAYING AT HÔTEL SAINT-MERRI, NEAR TOUR SAINT-JACQUES, ROOM 14.

SUPERINTENDENT FOURIER REQUESTS ASSISTANCE IN BRINDILLAC CASE (SEE

PARIS-SOIR

OF 16 OCTOBER ON MYSTERY OF ‘DEADLY SLEEP’)

STRANGE FEELING.

ANDREW

After dining at a restaurant in Bastille, I returned to my hotel where I spent the rest of the evening reading.

On the two days prior to his death, Gérard de Nerval had visited his friends, one after the other. He was penniless. Several days beforehand he had left his room at the Normandie and found himself homeless. Temperatures outside had dropped to freezing. Those who received him in their homes for a few minutes and others who met him in a reading room or a bar at Les Halles were worried when they saw him leave with nowhere to go, heading out into the snow and the cold, but they knew that there was no way of stopping him. He turned up at the home of Paul Lacroix, a scholar who used the pen name Bibliophile Jacob. He went to Joseph Méry’s but his friend was away. At a reception given by Madame Person, an actress, he had appeared gay and cheerful.

On the fateful evening of 25 January, on the banks of the Seine near the Hôtel de Ville, Nerval told his friend, the painter Chenavard, who had made it his duty to accompany him in his wandering, that ‘the way forward is clear; it must be followed. The baton is in the hand of the traveller.’

Then he had walked alone for a long time, taking any street he came to before, at the end of that evening, heading for Place du Châtelet – and Rue de la Vieille-Lanterne …

* * *

Late that night, I sat up in bed, my eyes feverish, disoriented by a dream so vivid that for a moment I believed that the scene had really just taken place in front of me. As soon as I had gathered my wits about me and, responding instinctively to the order I had been given in the dream, I grabbed the sheet of paper and pencil at the end of the bed and quickly noted down everything I had seen.

DREAM I

NIGHT OF 17-18-OCTOBER

Bedtime: 10.30 p.m.

Approximate time when fell asleep: 12.15 a.m.

Time awoken: 3.05 a.m.

I am stretched out on my bed and dreaming that I am asleep.

I am asleep and yet I am perfectly aware that I am in my room at the Hôtel Saint-Merri. In the semi-darkness I can make out the whitewashed walls, the beams crisscrossing the ceiling, the books on the table, my clothes on the back of the chair. I can feel the clean, starched sheets against my skin. A faint odour of wood and furniture polish wafts through the air.

I dream, aware that I am dreaming. I can actually see myself sleeping. It is a strange sensation – gentle and euphoric.

Suddenly, although I remember closing the door and locking it, I hear the handle turn, the hinges creak, and the door slowly opens. The figure of a woman is visible in the feeble light from the corridor. I cannot yet make out her face but I recognise her immediately: it is the stranger from the steamer. She is dressed in a green silk tunic, her feet are bare and her blond hair floats over her shoulders as if held up by invisible fingers. Her

presence casts a milky light on the objects around her.

As she moves into the room, my heart begins to beat so hard it almost jumps out of my chest. I would like her to come up to me, to sit down and take my hand. Instead, she heads towards the window, picks up a sheet of paper and a pencil lying on the table and slowly returns to the bed and lays them on the floor.

She stares at me without blinking. She is even more beautiful than I remembered. I feel she is about to leave me; I want to talk to her, implore her to stay a few more minutes but I have barely opened my mouth before she puts her fingers to my lips and commands my silence. Her skin is soft, surprisingly soft.

Then she steps away from me, still without uttering a word. As she moves towards the corridor, she repeatedly points to the objects on the floor. The sheet of paper and the pencil.

Before disappearing, she smiles at me as if to console me, encouraging me to be patient, telling me that she will come back. I follow her with my eyes until she’s gone. Then the noise of the door closing wakes me up.

1. As I recall, the sheet of paper and the pencil were on the table last night. But memories can be deceptive; this one must be deceptive. Without realising it, I put them at the end of the bed before going to sleep.

2. The sexual charge of the dream is undeniable and is not unknown in the malaise afflicting me. But why did the young woman insist that I record the contents of the dream on paper?

3. (Note added at 8.15 a.m.) Took a long time to fall asleep again. When I got up, I checked that the bedroom door was locked. It was.

In the morning, I bought a notebook at a shop on Rue Saint-Honoré and then sat outside a café where I wrote up the dream properly,

having scribbled it down at three o’clock in the morning almost automatically, together with the observations I had forced myself to record with as much clarity as I could at the time.

This I christened my dream notebook. It would come to play an important role throughout my life.

Clearly, dreams were to be significant during my time in Paris. Having come to find out the real cause of the death of Gérard de Nerval, for whom dreams and reality had constantly merged recklessly, I myself was now experiencing the ambiguous nature of the realm of dreams, at once so alluring and so pernicious.

Just for a moment, feeling suddenly fearful, I almost turned back and took the first train to London. But, as I was leaving the café, somewhere a bell chimed eleven o’clock and I instinctively hurried in the direction of the Seine, cut through the Tuileries Gardens and, crossing Pont du Carrousel, reached the Gare d’Orsay where Fourier and his constable, Dupuytren, were waiting for me on the platform for the express train to Orléans.

7

The Stavisky affair, which had come to light in December 1933, was still on everyone’s minds. Denounced by the press, the scandal of false credit bonds at Crédit Municipal in Bayonne had led to the fall of the Chautemps government. The investigation had revealed numerous fraudulent relationships between the police, the justice system and politicians. (Publisher’s note)

8

On 9 October, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Louis Barthou, was killed in an attack committed by a Croatian nationalist organisation, along with King Alexander I of Yugoslavia, whom he had gone to welcome at the port of Marseille. There was an immediate debate about failings in the police protection provided for such a high-risk visit. (Publisher’s note)

When we came out of Ãtampes station, the driver of an

old-fashioned

four-cylinder Colda called over to us.

âSuperintendent Fourier?'

âThat's me!'

âI am Monsieur Breteuil's chauffeur â he's the examining magistrate. He sent me. He's waiting for you at the château.'

âHow considerate!'

We drove for about three miles before reaching the entrance to the estate. Two sergeants were on duty, keeping an eye on the reporters and the curious who were crowding around the gates. Ever since the publication of the much-read article in

Paris-Soir

all comings and goings had been carefully checked in order to try to gather any snippets of information.

The gates were opened to let us through and the car sped up the drive leading to the château.

It was a charming manor house, a relic from a rich past â one of those houses that make the Ãle-de-France region so appealing today. The façade was fairly wide and two storeys high. Behind the imposing main body of the building were the narrow roofs of two medieval towers which could be seen from the direction of the village.

In fact, the château hadn't been built in the Middle Ages, but at the end of the sixteenth century and altered several times during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One restoration project had left more of a mark than the others â there were signs that the front

of the building had been added to an older section at the back or had at least been rebuilt from top to bottom along more modern lines.

As Superintendent Fourier had had time to explain to me on the journey, the Marquis de Brindillac had bought Château Bâ twenty years earlier to escape the hustle and bustle of the capital which had become unsuitable for the work he was carrying out.

Auguste Jean Raoul de Brindillac had been born on 28 April 1862. His father, Ernest Léon Honoré, had been an army surgeon, who in 1859 had married Marquise Joséphine Amélie de la Batte, granddaughter of a general during the Empire. They had had three children: Honoré, Auguste and Joséphine. After the death of his first wife, Auguste de Brindillac had in 1899 married Sophie Mathilde Van Doorsen, heiress of a wealthy Dutch family originally from Haarlem, with whom he had had two children: René, who had died in a hunting accident in 1926, and Amélie.

The Marquis de Brindillac, like his father before him, developed a vocation for surgery and anatomy very early on. He qualified as a doctor at the Ãcole de Médecine de Paris. An admirer of Bouillaud, and particularly Broca, he was passionate about physiology and the study of the human brain. He spent time at the laboratories of Marey, Berthelot and Vulpian. Following in the footsteps of Paul Broca, he focused his early scientific research on a better understanding of the limbic system or rhinencephalon, and on identifying the centre of speech in the brain. In 1894 he wrote a

Clinical and Physiological Treatise on the Location of the Language Centre in the Brain

which is still a standard work on the subject and led to him being elected to the Académie de Médecine de Paris in 1896. He was a professor of clinical medicine and physiology at the Hôpital de la Charité for a long time. The publication of his

Clinical Treatise on Disorders of the Nervous System

in 1909 definitively established his reputation as a leading scientist. In 1911 he was appointed dean of the Faculty of Medicine in Paris. In November 1924, he was elected to the

Académie des Sciences. The Marquis was without doubt one of the country's greatest minds.

The chauffeur parked on the drive, near the main entrance to the château, next to two saloon cars in the deep-blue colour of the French gendarmerie.

As we climbed the front steps, a short man of about sixty, whose hair and small goatee were as white as his skin, came to greet us. He was accompanied by a man who looked almost identical â same build, same pointed beard â but with slightly blonder hair, and twenty years younger. Behind him, a bald, plump individual was talking to a gendarme in the entrance hall.

âSuperintendent Fourier I presume?' said the pale man. âI'm Judge Breteuil and I've been appointed by the Versailles prosecutor's studyto handle this sad affair. Let me introduce Monsieur Bezaine, my clerk. Oh, and this is Monsieur d'Arnouville, the prosecutor's deputy, who was just leaving, and Second Lieutenant Rouzé, from the local gendarmerie.'

He indicated the two men from the hall who, having seen us, had come out on to the steps to join us.

âMonsieur, let me thank you for sending a car to the station,' said the superintendent to the examining magistrate.

âMonsieur Breteuil considered, quite rightly, that it was essential for you to reach the château as quickly as possible,' the prosecutor's deputy interjected with feigned politeness.

âIt would certainly have been a pity if we'd lost our way.'

âI was given to understand this morning that the police were about to open a new investigation into the death of this Pierre Ducros,' continued the deputy. âThe press is so powerful nowadays it can influence the decisions of the Seine public prosecutor's studyand the Préfecture!'

âI was under the impression that the Versailles prosecutor's

sudden volte-face was similarly influenced by the publication of a certain article.'

âIf you're alluding to the decision to open a judicial inquiry into the affair which brings us here, you're wrong. The public prosecutor never intended to close the case and he does not allow himself to be dictated to by anyone, especially not journalists.'

âThat is all to his credit.'

âOne thing is certain â the police don't need another scandal.'

âNeither does the justice system.'

âOh! But we haven't reached that point yet, gentlemen!' the examining magistrate intervened, fearing that tensions were rising. âBefore you arrived, Superintendent, we â the prosecutor's deputy, Second Lieutenant Rouzé and myself â were discussing the article published in

Paris-Soir

. At the moment, the press is doing everything it can to create a scandal. By the way, do we know who this J.L. is?'

âHis name is Jacques Lacroix. No one has seen him at the newspaper's offices in Rue du Louvre or at his home since Tuesday. It's a pity. I have a great deal to say to him. We'll soon track him down though.'

âWould it be indiscreet to ask your opinion of the two deaths, Superintendent Fourier?' asked the prosecutor's deputy.

âWell, I'm only here to investigate the death of the poor Marquis! And my investigations are only just beginning. It would surely be more instructive to hear Monsieur Rouzé's point of view since he's been involved in the Brindillac case all along?'

The gendarme opened his mouth to speak but Fourier had not finished and turned to me.

âBy the way, allow me to introduce Monsieur Andrew Fowler Singleton. Monsieur Singleton and his associate, Monsieur Trelawney, who is currently detained in London, helped the French police with a case that was in the news last year.'

âSingleton! Trelawney! Yes, of course, I remember it well!' exclaimed the examining magistrate. âYour names certainly made the papers at the time. I didn't realise you were so young though.'

After his initial enthusiasm, the magistrate's face darkened, as he reflected that, all things considered, my presence would cause a few problems.

âGood heavens, Superintendent,' he remarked with some embarrassment towards me, âdo you not think that this investigation has had enough publicity already?'

âOn the contrary,' retorted Fourier, unflustered. âAs the prosecutor's deputy confirmed, we need all the help we can get to solve this case as soon as possible. What's more, if, as the Versailles prosecutor's study believed less than twenty-four hours ago, the only strange thing about this death is the rather unusual circumstances surrounding it, then everything will be sorted out in no time. The Sûreté is going to use its expertise. With the help of our friend here, I wager that the mystery will melt away within two days. If the Préfecture acts with the same efficiency, it will be all to the good.'

âThat is exactly the attitude Monsieur d'Armagnac, the Versailles public prosecutor, asked me to convey, “Everything must be resolved as soon as possible!” I am glad that, on this point, we are all in agreement.'

Standing on the top step, the prosecutor's deputy concluded: âI've just hand-delivered the burial certificate to the Marquise. The funeral can be held this weekend. The Marquise would like the body to be returned to her today but I managed to convince her that, after five days, it was not a good idea. A van from the morgue will therefore take the body to the burial site once the date of the funeral and its location have been fixed. I'm sure that will be a great relief to the family. And now I must leave you, gentlemen. I'm expected in court.'

Monsieur d'Arnouville marched down the steps towards his car

and Judge Breteuil invited us to follow him into the château.

âI really don't like the way this investigation is looking,' he said. âYou'll see, it will be one of those cases we never manage to get to the bottom of. And I don't like this atmosphere of suspicion everywhere either.

And

I've been landed with it just a few weeks before I retire.'

âWell, we're here to find the explanation, whatever it is.'

âDying in your sleep is allowed,' continued the judge. âIt was even considered to be a very good end until last Saturday.'

âIt has long been said that Charles Dickens passed away in his sleep,' I said as we entered the building. âActually, the celebrated author died of a cerebral haemorrhage.'

Monsieur Breteuil and the clerk, Bezaine, exchanged baffled looks. Clearly, they had no idea what the British writer had to do with Château Bâ.

âBut as for the Marquis de Brindillac,' I continued, âdon't forget the look of terror on his face. Although it's not unheard of to die in one's sleep, it is a little more unusual to die during a nightmare!'

âTrue, very true,' conceded the judge, rubbing his head.

We had crossed a large hall and stopped in front of a door where a servant was waiting unobtrusively.

âThe Marquise and her daughter are in the sitting room,' explained the magistrate. âThey, and the château's staff, were interviewed by Monsieur Rouzé and his men during the first days of the investigation. As Monsieur d'Arnouville said, the burial certificate has just been delivered to them. The ladies are very distressed, gentlemen. Let us proceed with tact and sensitivity.'

We had come to a large stone staircase.

âOf course,' Fourier said. Pointing upstairs, he suggested, âWhy don't we leave them in peace for the moment and ask Monsieur Rouzé to show us where the Marquis was found? That will shed some valuable light on the matter.'

The magistrate agreed with this suggestion. He asked the servant

to inform the mistress of the house that he and Superintendent Fourier would speak to her in a few minutes' time and then invited us to follow him.

While the others began to climb the stairs, I stopped in front of a full-length mirror in the hall and considered my reflection. Despite all my efforts to make myself look older, my face remained as youthful as ever. It was exasperating. My bow tie and ragged moustache did nothing to improve the situation. Disappointed, I pushed my trilby more firmly on to my slicked-back hair and, frowning to make myself look sterner, caught up with the group in a few strides.

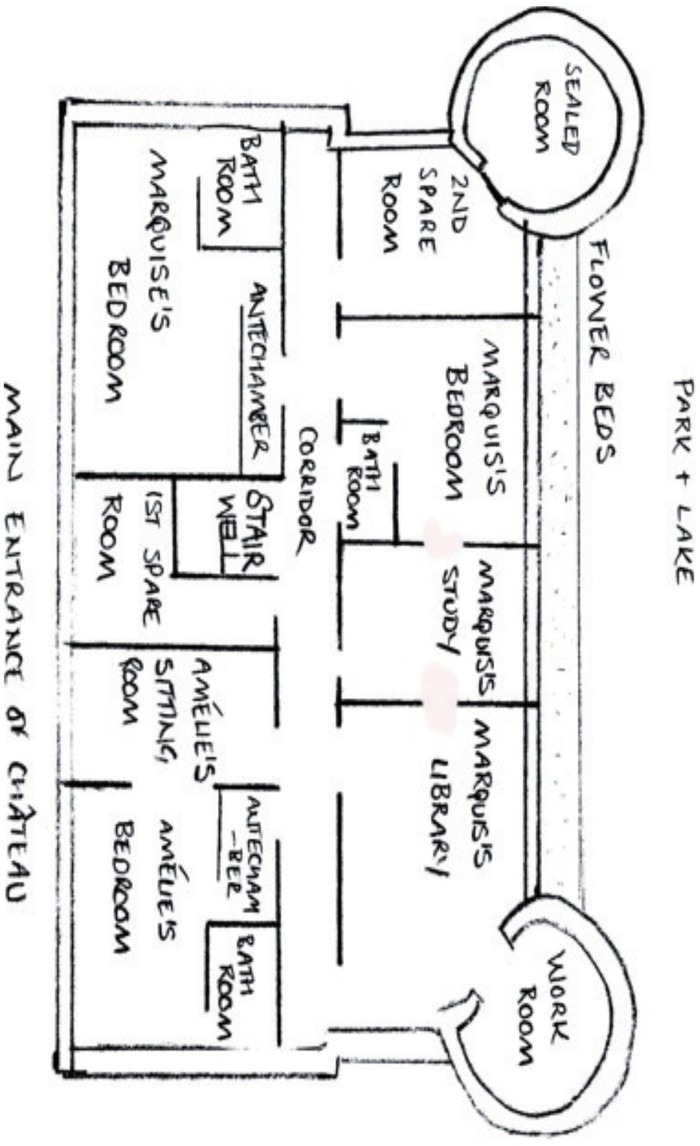

Upstairs, a corridor ran the full width of the château, dividing it into two parts of roughly equal size. On one side, at the front of the house, were the Marquise de Brindillac's bedroom and her daughter's apartments; on the other, Auguste de Brindillac's rooms, consisting of the bedroom where he had been found dead, a study and a large library. This perfectly geometric distribution was complemented by two spare bedrooms and, at the back, the two circular rooms situated in the towers. The first adjoined the Marquis's library and he used it for his experiments. The second opened on to one of the spare bedrooms but, for reasons still unknown to me, it had been sealed.

To help the reader visualise the layout of the château, I have appended a sketch of the first floor of Château Bâ, as well as a sketch of Auguste de Brindillac's bedroom (see page 50).

Second Lieutenant Rouzé preceded us to the door of the Marquis's bedroom. When the door had been forced, the servant and gardener had broken the lock so now all it needed was a push. The gendarme did this extremely slowly, as if he feared that the old scientist's body was still lying on the bed.

The room was large. To take it all in, we had to advance a few paces into it in order to see past the area on the right-hand side of the entrance which had been turned into a bathroom with all mod cons. Pushed up against the wall, an enormous four-poster bed immediately caught the eye. Its posts, made of high-quality wood, supported large sheets of fabric on which pink, round-faced cherubs few through bucolic landscapes. From looking at the bed, neatly made under the joyously festooned canopy, the sheets and covers pulled taut without a crease, no one could have imagined the tragedy that had occurred there.

Diagram of the first floor of Château Bâ