The Dressmaker's Daughter (30 page)

Read The Dressmaker's Daughter Online

Authors: Kate Llewellyn

(Nowadays Wilms’ disease is curable. In those days, they couldn’t operate on her.)

‘Basically it went on to the point where Joanne got pneumonia and it was pneumonia that actually killed her. The staff at the hospital thought we were bearing up extremely well and that we were handling the situation as best we could. But obviously S [Joanne’s mother] wasn’t coping very well and it was more than she could bear.

‘As clear as anything, I can remember Joanne’s death. I was reading the paper and I put it down and watched her take her last breath. What do you do? You are sitting there and then you have to think what the next logical step is. You have a dead child in front of you and how do you go on? What do you do? And the logical step is to tell the people in charge because they will know what to do. So I went over and said, “Excuse me, Sister, but Joanne has died.”’

Peter looks out at the sky. ‘It’s probably going to rain tonight,’ he says, before he continues.

‘The memories were too much for the marriage. The way I look at it now is that if we had stayed together, we would have had pain for years. S took off and got the whole thing over and done with. When you have been through that sort of pain, how do you survive, as a couple, the next few years? What do you talk about?

‘She knew a man who was working for us and she became friendly with him. They went off together, leaving me with Christina, who was ten, Michael who was five and three businesses to run. I developed a philosophy of survival. I had to look after two children who had lost their mother and their sister.

‘It seemed like an eternity to me. S left after Joanne died but I can’t remember how long afterwards that was. It was only a matter of months.

‘A man who managed our shop, Steve Vernon, said to me, “I am sick and tired of you looking so bloody miserable. There’s a girl working in the hotel who I’ve arranged for you to have a blind date with.” And that was Helen and we’ve been together thirty years now.’

‘Now,’ he says, leaning his elbow on the back of the couch, ‘do you want to go back to talking about the weather?

‘You know, there are sixty swallows on the powerlines out the front. That means that winter isn’t far away. And I would say that it is going to be an early winter. I think that mid-March is early for them to come.’

‘Why?’ I ask.

‘Well, they are not here in summer. They are migratory birds. They are only here in winter.’

‘Where do they come from?’

‘Buggered if I know. Most migratory birds come from the northern hemisphere. I wouldn’t think migratory birds come from the tropics, because they like the cold weather here…You know,’ Peter says, ‘when S left me, things got very nasty for a while. But later I said to her, “There was a meaning to all this. What happened to us was inevitable. If you hadn’t pulled the plug at that stage, we would’ve just suffered for many, many years.”

‘She gave me a hug and said, “Thanks very much.”

‘It was a great relief to her that I didn’t blame her any more. I hadn’t touched her in years, maybe twenty years, but she had lived with blame all those years. She said that it was the biggest mistake of her life. She wore dark glasses all that time so that people wouldn’t recognise her and blame her.

‘I think of parents who have lost a child as belonging to a special club. When I read of somebody losing their child I think, “Yes, you belong now to our club.” Sometimes I feel like writing to them, but I don’t.

‘Joanne is always there. I think of her regularly. The painful period is always the Melbourne Cup because she died the day after the Melbourne Cup. The way I

put it is that you never forget it but you learn to live with it. The last thing you want is for her to be forgotten. You don’t want to put it out of your mind. It is another part of life that you learn from. If you put it behind yourself and forget it and don’t learn from it, it has been a waste. You can’t let her life be a total waste. If you haven’t learnt something from her suffering and yours, what’s the point of it? If you can’t learn, how sad and terrible it is.’

Third from the left is our great-grandmother Mary Siekmann (nee Brinkworth); third from the right is our German great-grandfather Ernst Siekmann; and second from the right is our grandfather Thomas Anglesey Siekmann. Our grandfather, while he was at war, took his mother’s maiden name, Brinkworth.

Our father, Ron Brinkworth, in 1934. ‘Everything in moderation’ was his motto. I, his daughter, had a nature that was the complete opposite of this motto.

Our mother, Ivy Marjorie ‘Tommy’ Shemmeld, in 1934, before she married our father.

Our parents at their wedding in Angaston in 1935. Soon after, they left for Tumby Bay, where our father had been appointed to open the first branch of Elder Smith and Company.

Our mother, who our father nicknamed ‘Muttee’, holding my middle brother, Billy, in his christening robe. She is wearing a green frock she made for herself with silver bugle beads embroidered on the front of the shoulders.

Muttee, Peter, Bill and Tom (Tucker) at Tumby Bay, 1943. While my brothers and I swam or played on the beach, our parents would sit under a canvas awning and our mother would sew clothes for us all.

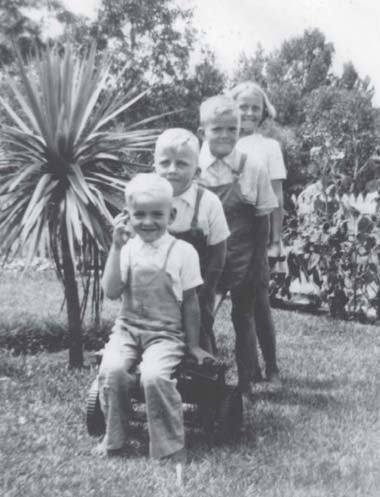

My brothers (left to right: Bill, Peter and Tucker) and me at Tumby Bay.

At the Puckridges’ station at Yallunda Flat are (front to back) Peter, Bill, Tucker and me. I loved visiting the Puckridges, who were friends of our parents; to me, their station had an air of luxury and opulence.

Tumby Bay School, 1943. Grades I, II, III. Tucker, with his piercing gaze, is sitting in the bottom row, third from the left. I am in the second row from the top, fifth from the right. Our teacher Miss Howard (standing at the back) gave me the gift of reading.