The Dulcimer Boy (3 page)

Authors: Tor Seidler

A

DROP OF COLD WATER

landed on his cheek, and he thought, The roof's leaking again.

Yet the bed felt curiously hard, and the air was not fusty, as it was in the attic, but cool and wild.

William rubbed the sleep from his eyes. Instead of roof beams there were the lordly boughs of pine trees high above him, higher than the ribs on the ceiling of a church. It was before dawn. The pieces of sky that showed through the trees were the color of his aunt's pewter dishes.

A shiver of memory went through him. He had broken the most treasured Carbuncle antique, stolen the dulcimer, and run off like a thief in the night, he knew not where.

He sat up and looked around. He had slept between two bulged-up roots, the astrakhan coat pulled over him. The forest was deep. The only sounds were the creaking of the high boughs in the breeze and the faint patter of dewdrops on the pine needles.

He was trembling. To calm himself he pulled the dulcimer from under the coat and began to pluck it. Its peaceful notes wandered out among the pines.

Suddenly the whole forest came alive with sound. His fingers froze; he lifted his eyes to the boughs above. All the birds in the forest seemed to have awakened at once: they were warbling, chirping, whistling, and singing. In

a moment, however, the symphony of sound died away, leaving only the creaking of the pines.

William resumed his playing. The birds started up again. He stopped, experimentally. They stopped. He started again, and the forest resounded.

Soon the sun rose in the sky, spangling the pine needles with gold. William's trembling was quite gone now. In fact, it was nice to be somewhere new, serenaded by birds. After a while he stopped playing and began to wind a finger in his hair, his thoughts widening like ripples on a pond.

He stood up and shook the pine needles from his coat. A sheaf of leaves fell out of its pocket and began to scatter over the brown-needled floor of the forest. He dropped the coat and ran after them.

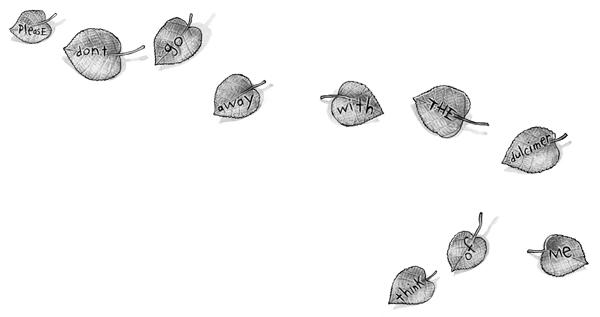

They were linden leaves, each with a word scratched into it. He laid them out between the two bulged-up roots.

He began to rearrange the scrambled leaves.

He found a number of messages, but they made grammatical sense only. Finally, however, he found the message, and his eyes shifted to one of the golden spangles. He saw an image of his brother, a golden figure crouched over the open trapdoor, while he, William, pressed his hands against the high glass doors of the mahogany secretary.

Slowly his eyes returned to the message.

A solemn feeling had stolen over him. He had the sensation of wings beating inside him, and as he saw another image of his brotherâthis time huddled in the slanted corner of the attic, silent and empty-eyed and forgottenâthe colors of the forest began to melt together before his eyes.

William stuffed the leaves back into the coat pocket and tucked the dulcimer under his arm. As he ran, his feet padded quickly and softly on the needled ground. He wove his way through the high-waisted trees.

But he had skipped dinner the night before, and long before he found his way out of the forest, the tails of the coat began to drag heavily behind him in the needles.

At last he emerged onto a meadowy downslope. Hooding his eyes against the noon sun, he looked out over a quilted countryside of apple orchards in blossom and meadows spotted with gray boulders and black-and-white cows. There

was not a sign of Rigglemore or the hill above it.

He wandered despondently down the slope and across a number of bouldery fields, having to climb several stone fences. He heard faint music. He hurried over a knoll, then fell to his knees and touched his lips to a brook.

His thirst quenched, he noticed fish shadows darting across the water. He broke off a willow wand, undid a string from the dulcimer, and fastened it onto the end of the wand. With the silver string, it took only a moment to lure one of the fish to the bank. He dashed his hand into the water. Nothing.

He squinted up at the sky and sighed, seeing that what he had thought were fish were only the shadows of a flock of dark forest birds circling overhead.

But at least he was not lost. A stagnant river went through Rigglemore, through the mucky section of town. Assuming this was the beginning

of it, he put the silver string back into his instrument and started downstream for home.

Little by little the music of the brook grew deeper. It became a stream. The stream widened into a river, and a road began to wind along the riverbank. William followed it, wrapping the dulcimer in the coat to protect it from the dust of the road.

He passed a number of people on the road, mostly farmers. One, the driver of a hay wagon, gave him a ride for a couple of miles and offered him a puff on his corncob pipe. William choked on the smoke, however, thinking of Jules. The rest of the farmers were a pithy bunch. None would commit himself on how much farther it was to Rigglemore; none had any food to give him; all eyed with suspicion the dark birds circling over his head.

It was painful to look at the cows in the meadows, chewing their cuds so contentedly. He

fixed his eyes on the distance. Nothing looked familiar. But he noticed a strange, flat blue cloud forming on the far rim of the horizon.

By late afternoon he was weak from hunger. He tugged rather desperately on the coattails of fellow wayfarers, asking if this was indeed the way to Rigglemore. Many of them shook him off. A few replied, “Mebbe,” or “Not as I know of.” Most discouraging of all was the woodsman who laughed and said, “But you're not wriggling now, ladâwhy do you want to know the way to wriggle more?”

Finally, as dusk stole over the countryside, William became conscious of a roaring in his ears. This was a bleak sign. After a few more steps he collapsed on the roadside.

He lay on his back, staring up at the twilit sky. It came as little surprise to him that he should be seeing things: white things, circling among the dark forest birds overhead. Yet blinking only

brought the hallucinations into sharper focus.

Suddenly he sat up and unwrapped the dulcimer. He stared from the mother-of-pearl seagulls inlaid along the sides to the white things in the sky. They were identical.

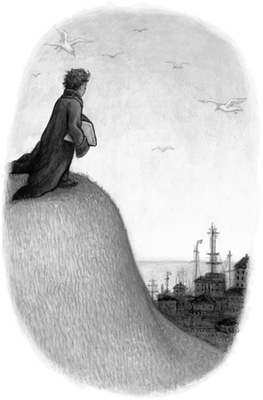

Somewhat revived, William got to his feet and continued along the road beside the river. The roaring in his ears grew louder, and in less than a quarter of a mile he found himself standing on the edge of a promontory. The river plunged over itâa roaring waterfall.

There was a broad plain below, and to William's surprise there were a number of rivers winding their ways across it; he had not imagined there were more than one. Beyond the plain lay the flat blue cloud that had captured his attention earlier. It went on forever in the evening light, its dark surface shimmering with movement.

“Dark and never still,” he murmured.

Beyond the plain lay the flat blue cloud

The rivers on the plain below all finally merged and entered the dark expanse of a great harbor, around which was built a city that looked a hundred times the size of Rigglemore. William set off down the steep road, his eyes on a beacon that swept the sky from a lighthouse at the harbor's mouth.

He entered the great city on a wide, elm-lined boulevard. Facing each other across the boulevard were fine, stately houses with balconied rooftops, standing in rows like the elegantly bound volumes in the Carbuncle library. It was the hour when lamps were being lit: through bay windows he saw crystal chandeliers and mantelpieces displaying ships in bottles. But it was also the dinner hour, and as he passed along, he smelled food. Ham with raisin sauce. Sausage and baked beans and hot brown bread. Rack of mutton. Codfish and boiled potatoes in melted butter.

Finally from an ivy-covered town house came the smell of roast beef and Yorkshire pudding. His will defeated, William walked up the steps and knocked.

The door was opened by a butler in tails and patent leather shoes.

“Excuse me, sir,” William said, “but I'm lost andâ”

“Indeed you are.” The butler nodded. “This is Park Row, not Pawn Street.”

William hastily combed his fingers through his sweaty, dusty hair.

“But you see,” he said, “I've come an awfully long way and I smelledâ”

“You're quite right.” The butler nodded again. “You do smell.”

The door closed in his face. Turning away, William continued down the gracious boulevard. He asked the first person he met the way to Pawn Street.

“Down that way, then down around there,” he was informed.

These directions took him across a bridge, past a great university, across another bridge, past a domed statehouse, and finally into a quarter where the streets were oily and lined with neither elms nor street lamps. The air had turned dark and briny. The gutters were littered with fishheads and oyster shells. Soon he found himself leading a file of alley cats, who seemed to be taken with the birds flying over his head.

He turned onto Pawn Street, which ran along the wharves. Here and there squares of yellow light fell onto the street from the windows of cheap hotels, giving the oil on the street a sinister sheen. There were noisy, dimly lit taverns as well, but when he peered in the windows, he saw countless glasses and tankards but not a single plate. Finally he collapsed in the gutter. He raised his head out of the refuse,

took a last look at the mangy cats with their greedy yellow eyes, and passed out.

He dreamed that he was swimming in a great vat of clam chowder. It was very realistic; in fact, he could actually smell it. He opened his eyes and saw the open doorway of a seedy-looking establishment across the street: The Tumble Inn, according to some flaky lettering. He got up and followed the smell of clam chowder through the doorway.

It was not crowded like the taverns up the street. The only customers were a few sailors seated at round tables. None of them noticed him, for they were all staring at a lady in a short dress who was singing squeakily and wiggling on a little, well-lit stage. He could now smell minute steaks and seafood platters as well as clam chowder.

Opposite the little stage was a bar tended by an innkeeper with moist eyes and a droopy

moustache. A door swung open at one end of the bar. A waitress with a tray of food and drink plodded across the sawdust floor to one of the round tables.

William went over to the bar and peered over the polished counter at the innkeeper.

“Excuse me, sir, but I've lost my way and haven't eaten since yesterday lunch, and I've come so terribly far.”

“Come again?”

William repeated his little speech.

“Where are you from?” the man asked doubtfully.

“Rigglemore, sir.”

“Come again?”

“Rigglemore, sir.”

“Never heard of her,” the innkeeper sighed. “I don't suppose she's much of a rig.”

“Not a rig, sir. Rigglemore. It's a town.”

“Ah. I figured she wasn't much.”

William watched a waitress plod out of the swinging door with another tray of food. The innkeeper, with his moist eyes and droopy moustache, could not have been less intimidating, and William asked right out if he might have something to eat.