Authors: Tor Seidler

The Dulcimer Boy (2 page)

A

FINE LINDEN TREE

stood in the yard of the Carbuncle estate, its roots rivering over the lawn. The attic windowâa little round window in the gableâgave directly onto this tree, and on sunny mornings the boys were awakened in their bed by the nervous sunlight that jiggled in through the leaves. They would lie there and listen to the swallows that nested under the eaves.

Winters in the attic were less idyllic. It was unheated, and year by year the old cedar shingles were rotting off the roof, letting in more of the cold. Mr. Carbuncle, who had begun to speculate in gold, had long promised to reshingle. But the

promise remained unfulfilled, and to keep their blood circulating, the boys paced the attic in a huge astrakhan coat that Morris had discarded when astrakhan went out of fashion.

One winter Jules began to mope. William reminded him that the swallows would be coming back, but to no effect. Finally William convinced their aunt to let them move back down into one of the bedrooms. But Jules refused.

Spring came, and to William's dismay Jules failed to perk up. The songs of the birds, which Jules had always particularly loved, held no charms for him now. One perfectly nice morning he did not even get up for breakfast, and after the meal William went up to find him huddled in the corner under the slant of the roof.

“Feeling mopey?” William asked.

Jules shrugged.

Jules failed to appear at lunch as well. None of the three Carbuncles so much as noticed his

absence. After lunch William went up and found Jules still huddled in the same corner.

“Feeling fluish?” he asked.

Jules shrugged. William stared at him. Usually Jules's eyes were like two small blue pools, but now they looked empty, as if the plugs had been pulled.

When Jules was not at the dinner table that evening, William could not touch his food and excused himself before dessert, bent on discovering once and for all the cause of his brother's listlessness. He searched the upstairs for a pencil and paper for Jules to write with. But when he opened the top drawer of the mahogany secretary, the brass pulls rattled on the lower drawers. He had hardly found the box of paper when he got a whiff of disinfectant.

Mrs. Carbuncle came around the head of the staircase. “So now you're putting fingermarks on our finest piece of furniture. I

thought as much when you skipped pudding. And what do you think you're doing with Mr. Carbuncle's stationery?”

“I want Jules to write down what's wrong with him.”

“Really?” she said. “I didn't notice anything particularly the matter with Jules today.”

“But, Aunt Amelia! He hasn't been down all day long!”

“Hasn't he? Well, I'm sure I wouldn't know about thatâthere isn't a peep out of him whether he's there or not. But I do know paper doesn't grow on trees. Stationery like that costsâ¦Look at me when I'm speaking to you!”

She saw what he was staring at, and then she sighed, pulling a key from a pocket of her apron.

“I've seen you ogling that before,” she said. “Will you keep your fingermarks to that if I give it to you?”

William nodded, speechless. She unlocked

one of the high glass doors and handed the strange musical instrument down to him.

“Mine?” he whispered.

“Well, it came with you.”

William ran his fingers gently over the instrument. The wood was time-polished, and the strings were silver.

Mrs. Carbuncle turned to go down to her dinner dishes.

“Is itâ¦a dulcimer, Aunt Amelia?” he asked.

She turned around, her eyebrows raised.

“How'd you know that?” she asked.

Â

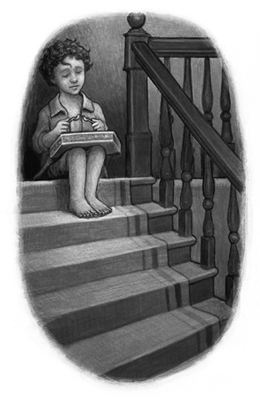

Soon he was alone. He sat down on the top stair with the dulcimer in his lap and ran his fingers over the sides of the instrument, which were inlaid with seagulls in mother-of-pearl.

There were two little cork-headed hammers tied by a slender thong to one of the dulcimer's pegs. Using one of these, he struck the silver

strings. Morris, passing by on his way to lie down for the evening, made a sour face.

He sat down on the top stair with the dulcimer in his lap

William stared down at the dulcimer in surprise, winding a finger in his nut-brown hair. He tried again, making sure the hammers struck the strings squarely. It sounded just as bad.

He began to fiddle with the pegs, changing the tuning of the strings. He tuned and tested, tested and tuned, losing all track of time.

At last he ran a finger over the strings like a harp and produced a sound that did not grate on his ears. Then, however, he found himself at a loss. The Carbuncles were not a musical family. He did not know a single song.

As he let the cork hammers wander over the strings, he had to smile at his luck. Almost immediately a tune began to emerge out of the random notes. It was simple but quite pleasing. He practiced it over and over and over.

Suddenly he heard the tinkle of ice. It was

the ice in Mr. Carbuncle's nightcap; his aunt and uncle were coming up to bed. It was ten o'clock, and since coming up after dinner, he had not once heard the grandmother clock at the end of the hall strike the hour.

He sprang up the ladder, the dulcimer under his arm. Only as he lowered the trapdoor behind him did he remember his brother.

Jules was sitting in the corner of the dim attic, his arms around his knees, his head hanging down, asleep. William set the dulcimer aside and carried his brother to bed. He hardly seemed to weigh a thing.

As he set him down, Jules woke up.

“Is your appetite back?” William asked, pushing back Jules's disheveled golden hair and feeling his brother's brow.

Jules did not seem to be running a temperature, but his eyes were still empty. William began to search for something to write with. But

except for their bed, and a box of clothes, and the astrakhan coat hanging from a nail in the roof beam, the attic was bare.

Then he remembered what his aunt had said about paper not growing on trees. He opened the little round window, thrust his hand out into the night, and pulled in a bunch of new linden leaves. He took down the astrakhan coat and worked the nail out of the roof beam.

Sitting on the edge of the bed, he handed his brother the writing materials and asked what was the matter. Jules sat up. He took four leaves and scratched a word on each with the nail.

William stared at the message for some time.

He had spent every day of his life with Jules, but this was the first time Jules had spoken to him.

William looked from the leaves to the golden head, the hollow cheeks, the empty eyes. A solemn feeling came over him. His heart felt quivery. It was strange, sudden, as if wings were beating inside him. It was as if his heart were leaving him entirely.

The dimly lit attic was becoming unsettled. Things were running together like watercolorsâ¦he and Jules.

Wiping his eyes, William went over to get the dulcimer. He sat down on the bed again and struck the cork-headed hammers lightly on the silver strings. He began to sing.

“The one I love was like the tide

That runs under the quay,

Smoothing the wrinkles on the shore

Only to fall away.

“For the sea is dark and never still.

It never will obey

Hearts that are in the likes of me.

My love is gone away.”

He sang the song to the tune he had practiced, singing in a clear, quiet voice as if he had known the words since the day he was born. When the song was finished, Jules's eyes were shining.

W

ILLIAM MADE REMARKABLE

progress on the dulcimer. He found he had a knack for making up songs. Before long Jules had several favorites. And when another winter came, the dulcimer could make them forget the cold.

One morning they were awakened by the first party of swallows arriving under the eaves.

But this spring turned out to be different. While the rest of Rigglemore grew brighter, the Carbuncle household only grew gloomier. The latest brands of tonic for baldness and the boxes of crisp cigars stopped arriving for Mr. Carbuncle from New York. Morris, feeling

victimized at having his clothes allowance cut off, began to stay in bed on school days, asking to be brought elegantly bound books from the family library. One night, after drinking a lot of brandy, Mr. Carbuncle used his gold mining shares to light a fire. The next morning he hinted darkly that the family antiques, perhaps even the estate itself, might have to go under the hammer. Mrs. Carbuncle continued to clean.

One evening at dinner Morris unveiled a phrase he had gotten out of one of the elegantly bound books.

“Fiddling while Rome burns,” he said, staring at William and Jules.

After this, when William and Jules came down to meals, Mrs. Carbuncle was wont to say, “Don't think we don't hear you playing that miserable music.”

William hung his head over his plate. Up in the attic after the meal, however, Jules would

write him a message in leaves to the effect that his playing was not miserable at all.

One afternoon not long after Easter the town auctioneer paid the Carbuncles a visit. A dry, leathery old man, the auctioneer made a tour of the house, rapping pieces of furniture with his knuckles, fastening yellow tags onto brass handles, peering at the signatures on paintings, and speaking of the worth of everything in a voice so rapid that the words sounded like cards being shuffled. William and Jules, however, were not allowed to witness these curious proceedings for long. In the course of his appraisals the auctioneer naturally left many fingermarks, and needing to take her distress out on someone, Mrs. Carbuncle soon screamed at the boys to keep out from underfoot. So they went to sit under the linden tree, where William played suitably mournful songs on the dulcimer.

The sun had fallen below the roof of the

house when the auctioneer appeared on the front porch with the three sullen Carbuncles.

“Well, that's the lot then,” he said as they started for the gate in the picket fence. “The truck'll be here tomorrow for the things. Sunup, so none of your neighbors'll be the wiser.”

He stopped under the linden tree.

“What have we got here?”

“Our two objects of charity,” Mr. Carbuncle replied.

“Not the youngsters. I mean that.”

William stood up. “This is my dulcimer, sir.”

“A dulcimer, is it? Why, it looks like a dandy. Let's have a gander.”

William proudly handed over the instrument. The auctioneer ran his leathery hands over the time-polished wood and the silver strings.

“Don't see one of these every day,” he murmured to the Carbuncles. “Looky here, mother-of-pearl down the sides as pretty as

you please. Yes, siree, all dressed up and nowhere to go.”

“You don't say,” Mr. Carbuncle said, brightening a little. “It's not worth anything, is it?”

“Not more'n four or five hundredâif a body knew how to talk it up.”

“Really! Did you hear that, Amelia? Perhaps these tykes can earn part of their keep, after all. They've been something of a burden to us over the years, you know.”

“Oh, I know,” sighed the auctioneer. “All Rigglemore speaks of your charity.”

Mr. Carbuncle, now almost cheerful, watched complacently as the auctioneer fastened a yellow tag around one of the instrument's pegs. William looked on in stunned silence.

“But it's mine!” he finally cried, finding his tongue.

Mr. Carbuncle, taking the dulcimer, had

little trouble holding it out of William's reach. Mrs. Carbuncle sighed.

“Think of itâraising his voice like that to his benefactor.”

“A sad business,” said the auctioneer, wagging his head.

Morris chose this moment to unveil another phrase from one of the elegant volumes.

“Ungrateful children are sharper than serpents' teeth,” he announced.

“Yes,” Mr. Carbuncle agreed. “A most ungrateful, ungentlemanly business.”

Mrs. Carbuncle whisked the dulcimer off into the house. Mr. Carbuncle magnanimously walked the auctioneer all the way to the gate.

“Until dawn then,” he said.

When he turned back to the house, he paid no attention to William tugging on the tails of his smoking jacket. Nor did he pay any attention to the desperate pleas that dogged him around

the house. But when they sat down to a New England boiled dinner and William had still not let up, Mr. Carbuncle lost his equanimity.

“I'm in no mood for this,” he said. “My furniture is covered with tags. My house looks like some kind of shop. But I ask one small sacrifice of you, and what do I get? Sniveling.”

“There now!” said Mrs. Carbuncle, as if just what she had expected had happened. “You've ruined Mr. Carbuncle's digestion with your selfishness. Go up to your room this minute.”

William excused himself, having not even touched his dinner.

When he was halfway up the ladder to the attic, he felt a tug on the cuff of his pants. He looked down and saw a golden blur.

Jules had followed him from the table. He seemed to be pointing at something.

William climbed back down and wiped his eyes. Jules was pointing at the high glass doors

of the mahogany secretary, behind which lay the dulcimer. It looked stranger and lovelier than ever before.

William reached up and tried the latch. The glass doors rattled, locked.

They both stepped back, smelling disinfectant. Their aunt was standing at the top of the stairs, her arms crossed over her apron top.

“The one thing Mr. Carbuncle didn't have it in his heart to part with and you have to smudge it,” she said. “Didn't I tell you to get up there?”

She pointed to the ladder. But William was now entranced by the dulcimer, shimmering behind the watery glass.

“William, didn't I tell you to get up there?”

He still failed to acknowledge her. She took him by the shoulders. He turned and looked at her blankly.

“Why, you'd think I was talking for my health!” she said as she pushed him toward the

ladder. “Now get up, and don't let me lay eyes on you before breakfast.”

Soon he was lying at his brother's side in the dim attic, staring up at the slant of the roof. On the floor below, the grandmother clock struck the hours. At ten he heard their aunt and uncle trudge up to bed. Then the silence of the house was disturbed only by the loose, rotten shingles, flapping on the roof in the wind.

After midnight a cold blade of moonlight came in the little round window. William slipped out of bed. Jules, rolling over quietly, watched his brother disappear through the trapdoor.

William stood before the mahogany secretary. Slowly he lifted his hands to the glass doors that glimmered in the moonlight from the window on the landing.

He recognized the muffled sounds of his aunt's and uncle's snores: one a high, thin

sound, the other a deep, grunting wheeze. Bending down, he eased out the bottom drawer of the secretary. It creaked. He withdrew a brass candlestick from the drawer and then used the drawer as a step, standing on it.

He hardly had to touch the glass with the candlestick for it to shatter. As the pieces showered down onto the floor, a little triangle of the broken glass fell into his shirt pocket. He grabbed the dulcimer.

A doorknob turned, and then he smelled disinfectant. As he leaped down off the drawer, his aunt uttered a piercing cry. Then something huge and dark floated down from above, settling over his shoulders like a cape.

His aunt ran at him, screaming like a crow. He fled down the stairs and out the front door into the moonlit yard. His aunt was at his heels. Suddenly she shrieked. He looked over his shoulder and saw her lying facedown on the

ground. She had tripped on one of the linden roots that rivered up on the lawn.

The tails of the huge astrakhan coat flapping out behind him like wings

It was all he needed. He raced through the gate in the picket fence and down the hill, the dulcimer under his arm, the tails of the huge astrakhan coat flapping out behind him like wings.