The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (7 page)

Read The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 Online

Authors: John Darwin

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Modern, #General, #World, #Political Science, #Colonialism & Post-Colonialism, #British History

Of course, there were places where the British had little to fear from the interference of France, Russia or the United States, although fewer perhaps than appeared at first sight. Palmerston ruled out the invasion of Persia (to stop it seizing Afghan Herat) in 1838 on the ground that it would only drive the shah closer to Russia. Instead, Afghanistan was to be ‘saved’ by an invasion from India – a costly calamity. Once the Russians were entrenched to the north of Manchuria, their reluctance to support the Anglo-French coercion of Peking eased the pressure on the Manchu court.

25

Even where and when the British were free to apply their military power, they had to weigh up its costs against any possible gain. Their great asset was the Navy. Most of its powerful units had to be kept at home or in the Mediterranean to watch the French and the Russians. But, with nearly 200 ships, there were plenty to spare. A squadron blockaded the River Plate estuary between 1843 and 1846. Brazil was blockaded in the 1850s to enforce a ban on the slave trade.

26

Twenty gunboats on average patrolled the West African coast to stop the still-vigorous slave trade. The British assembled a fleet of forty ships (including numerous steamers) to force open China's trade in the first opium war.

27

Yet naval power had its limitations. It could bombard, blockade and police the sea-lanes. But bombardment was risky and required heavy-weight firepower. A blockade was as likely to damage British trade as to check errant rulers.

28

The slave trade patrol produced embarrassingly feeble results: in the four years after 1864, it caught a total of nine slaves. The most striking success was perhaps against China in 1840–2. This was not because naval force could be used directly against the Ch’ing government. But, by entering the Yangtse and seizing its junction with the Grand Canal, the British could paralyse China's internal commerce and bring the Emperor to terms.

Away from the sea, the spearhead of power, and its last resort, was the British regular army. Its strength had drifted upwards from 109,000 in 1829 to 140,000 by 1847.

29

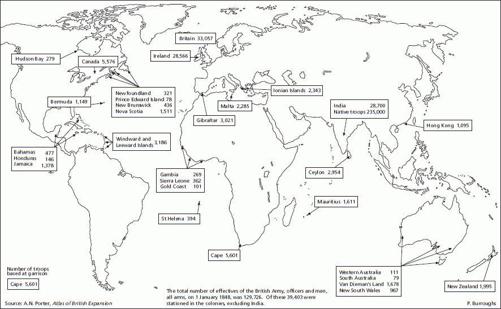

Between 25,000 and 33,000 men were usually stationed in India (the number rose sharply during the Mutiny) as the praetorian guard of Company rule. A smaller number, perhaps 18,000, were at home in Britain. Much of the rest was scattered in packets across the colonies and Ireland (where around 18,000 men were normally kept

30

). This system depended, remarked an experienced general, on ‘our naval superiority, and our means of conveying troops with great rapidity from one part of the world to another, which multiplies, as it were, the strength of our army’.

31

Even so, it was thinly stretched. Between 5,000 and 6,000 men defended Britain's North American provinces. In the Cape Colony, the 400-mile frontier, where raiding and reprisal were constant between whites and blacks, was guarded by a single battalion of infantry too encumbered with equipment to chase cross-border intruders.

32

Its reinforcement was 600 miles away in Cape Town and the whites in the region depended instead on their local commandos (volunteer bands of notorious ferocity) for defence and revenge. Twelve hundred men sent to New Zealand

Map 1 Distribution of British troops, 1848

in 1845 fought a pitched battle with Maori at Ruapekapeka in the North Island, but lacked the strength to compel their acceptance of British authority.

33

In effect, the army was a collection of garrisons whose main purpose was to protect the colonies from attack by an imperial rival or a revolt from within (as in Ireland, French Canada and British-ruled India). Fifty thousand men were scraped together in 1854 for the Anglo-French assault on Sebastopol, but, with that inglorious exception, the offensive power of the British on land was really pivoted on India, where the Company maintained an enormous army (until after the Mutiny of 1857) of some 200,000 men. The British regiments there could be combined with sepoy battalions to form a respectable force. Of the ten thousand men sent to China in 1842, the larger part were Indians. In the second China war (just after the Mutiny), they made up just under half of the British contingent. It was from India that expeditions could also be mounted into Persia, Afghanistan, Burma and Abyssinia. It was India that made the British a military and not just a naval power – but a military power whose active sphere was almost entirely confined to the world south and east of Suez.

In the 1830s and 1840s, we can see that a certain geopolitical ‘logic’ was imposing a shape on Britain's place in the world. In the official view from London, Europe bulked largest and posed the most danger. No set of ministers was likely to forget the lesson of what was still called the ‘Great War’. Their first priority was to preserve the chief gain of 1815 – and prevent the rise of a European hegemon. For all his bluster, Palmerston stood on the defensive in Europe, watching apprehensively over the Low Countries, Portugal, Spain and the Eastern Mediterranean. In North America, too, the British watchword was caution, lest the populist anarchy of American politics unleash an invasion which they would have to repel – perhaps at a difficult moment. Naval power was deployed on the South American coast in the 1840s and 1850s. But its utility in extending British influence there was open to question. The blockade of Brazil forced a stop on the slave trade but failed to induce a more liberal tariff.

34

There was little enthusiasm for using military power to advance the colonial frontier. When the cost of the South African garrison shot up to over £1 million in the late 1840s (as a result of its frontier wars), London quickly abandoned the highveld interior to the Boer republics. When Whitehall gave way to the urgent request from New Zealand in the mid-1860s, and sent 10,000 men to crush Maori resistance, it did so expecting the cost to be borne by the settler government in Wellington and was enraged when it was not.

35

Only in the sphere where Indian power (both naval and military since the Persian Gulf was patrolled by the Bombay Marine and it was Company steamers that were sent to China in 1842) was available to them could British governments take the lead in advancing British influence. Even there (as we have seen) the limits of action were narrow. Almost everywhere else, the task of building an empire, whether formal or not, fell to private interests at home and to the ‘men on the spot’.

Making Empire at home: domestic sources of British expansion

Commerce

‘The great object of the Government in every quarter of the world was to extend the commerce of the country’, Palmerston told Parliament in 1839.

36

This was not a new doctrine. The close inter-relation between power and profit was proverbial wisdom. Few public men would have denied the connection between overseas trade and Britain's strength as a state. The contribution of trade to taxable wealth, to Britain's ability to subsidise allies in wartime, and to the vital reserve of skilled naval manpower, was well understood. Without overseas trade, empire was redundant, a futile extravagance. Trade was the source of most colonies’ revenue and helped to defray the cost of their garrisons. It could also be seen as a great arm of influence. ‘Not a bale of merchandise leaves our shores’, Richard Cobden declared in 1836, ‘but it bears the seeds of intelligence and fruitful thought to the members of some less enlightened community…[O]ur steamboats and our miraculous railways are the advertisements and vouchers of our enlightened institutions.’

37

In the 1830s and 1840s, the expansion of overseas trade took on a new urgency. New markets were needed for the swiftly rising production of textiles and ironware, to avert depression, unemployment and strife in industrial districts. Britain's domestic tranquillity required the growth of its trade.

The leading role in promoting the expansion of trade was played not by governments but by merchant houses, especially those based in the largest ports: London, Liverpool and Glasgow. The sum of their efforts might be likened to creating a vast commercial republic, embracing Britain's empire but much else beyond. Its scale can be seen in the statistics for exports whose nominal value had risen from some £38 million in 1830 to £60 million in 1845 and £122 million by 1857. They were matched by the fourfold increase between 1834 and 1860 in the tonnage of shipping that used British ports.

38

From its old concentration in the Atlantic basin, British mercantile enterprise had spread round the world by the mid-nineteenth century. In the late 1840s, a census revealed around 1,500 British ‘houses’ abroad, nearly 1,000 outside the European mainland, with 41 in Buenos Aires alone.

39

The most notable feature of this commercial expansion, apart from the overall increase in volume, was the shift towards markets in Asia and the Near East (up from 11 per cent of exports in 1825 to nearly 26 per cent in 1860) and in Africa and Australasia (up from 2 per cent to over 11 per cent).

The speed with which British merchants moved out to search for new business, their success in constructing new commercial connections and their dominant position in long-distance trade made Britain

the

great economic power of the nineteenth-century world. This great expansionist movement arose from the junction of favourable forces already apparent by the mid-1830s. British merchants were the immediate gainers from the opening of the trade of Brazil and Spanish America during the Napoleonic War: indeed, wartime Brazil had been virtually a British protectorate. The release of British trade with India (1813), the Near East (1825) and China (1833) from the regime of chartered monopolies encouraged a flood of new enterprise. The rapid development of the American economy after 1815 was another huge benefit. With its favoured position at a maritime crossroads (where the shortest transatlantic route crossed the seaway linking the north and south of Europe), Britain became the main entrepot for the New World's trade with the Old – just as it was for the seaborne trade between Europe and Asia until the cutting of the Suez Canal in 1869. By 1815, London had replaced Amsterdam as the financial centre of Europe, partly because of the wartime blockade of the European mainland, partly because it had been at the centre of a Europe-wide web of war loans and subsidies. The supply of long credit on easy terms from London was the key to business with regions where the local financing of long-distance trade was underdeveloped or lacking. Above all, by the 1830s, with the arrival of power-weaving, the British could undercut competition across the whole range of cotton manufactures (the most widely traded commodity), and break into new markets with products as much as two hundred times cheaper than the local supply.

The main agent of commerce was the commission merchant, usually in partnership. He took goods on consignment from manufacturers at home and a share of the sale price when a buyer was found. In the 1830s and 1840s, there were powerful incentives to search hard for new outlets. Although Britain's industrial output was growing, nearby markets in Europe were either closed altogether against foreign industrial goods, restricted by tariffs or comparatively stagnant. Some manufacturers gave merchants a free hand to sell at cost price or less – a form of dumping.

40

Armed with cheap credit, equipped with cheap goods, the merchants searched for customers wherever opportunity offered. Of course, the conditions they found were bound to vary enormously, and so did their methods. Henry Francis Fynn, a ship's supercargo, went ashore at Delagoa Bay in 1822 and paddled up-river, looking for ivory to exchange with his trinkets and bolts of cloth.

41

As late as the 1880s, some trade in West Africa was still conducted from ships sailing along the coast, waiting for locals to venture out through the surf.

42

Few British traders ventured far inland or were allowed to do so by African middlemen resentful of interlopers. Much of Britain's trade with the United States was soon in the hands of American merchants: the role of the British was to supply the finance, to become ‘merchant bankers’.

43

In Latin America, British merchants sometimes went into partnership with local Creole merchants to widen their contacts and enlist local finance. In Brazil, British merchants quickly established a dominant position in the sugar and coffee trades, Brazil's principal exports.

44

In Canada, the fusion of the Hudson's Bay Company and its Montreal rival, the North West Company, in 1821 built a powerful nexus of Anglo-Canadian businessmen including Edward ‘Bear’ Ellice (Palmerston's

bête noire

), Andrew Colville, Sir George Simpson, Alexander Wedderburn (brother-in-law of the Earl of Selkirk), Curtis Lampson (a key figure in the laying of the Atlantic cable and grandfather of the proconsul Miles Lampson, Lord Killearn) and Alexander Matheson, nephew of the co-founder of Jardine Matheson, a Bank of England director, and the biggest fish in the China trade. In India, British merchants were usually partners in one of the ‘agency houses’ to be found in Calcutta and Madras, whose original purpose had been to remit home the earnings (one might almost say ‘winnings’) of the East India Company's ‘servants’. Agency houses dealt with imports and exports but also acted as bankers to Europeans working in India and managed plantations and processing plants (in jute or indigo) for their European owners. Agency houses spread from India into Burma and other parts of Southeast Asia in the first half of the century. When direct British trade with China (and the right to buy tea) ceased to be an East India Company monopoly after 1833, British houses (with Jardine Matheson in the van) were quickly set up there.

45