The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (21 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

Friday 18

Jimi Hendrix

(Johnny Allen Hendrix - Seattle, Washington, 27 November 1942)

The Jimi Hendrix Experience

The Band of Gypsys

(Various acts)

‘It’s funny how most people love death. Once you’re dead, you’re made for life - you have to die before they think

you’re worth anything.’

Jimi Hendrix, 1968

Whether in the guise of blues guitarist, psychedelic icon or smouldering ladies’ man, we’ll never see the like of James Marshall Hendrix again. The man trucked on in, lit a real big fire and then checked out before he’d had a chance to see what those flames might attract or indeed where they might catch next. Hendrix’s own little inferno died there and then, music’s loss now mythology’s gain.

Despite Hendrix’s denial of the fact (and even his occasional claim that the man wasn’t his biological parent), his father loved both him and his body of work; the musician’s estranged mother had died early, a victim of alcoholism. Al Hendrix – who had given his son his guitar and thus the identity that would capture the imagination of generations – was a pretty mean saxophone-player himself, accompanying the fledgling musician at home. Childish drawings of Elvis Presley showed from where Jimi Hendrix’s love for rock ‘n’ roll stemmed, but he was also well educated in the blues, forming his own rhythm bands in Seattle while a teen. In his youth, he’d displayed many of the hallmarks of his future rock lifestyle, finding himself in trouble with the law and then earning a ‘generous’ medical discharge when a spell with the Kentucky-based 101st Airborne Division didn’t quite work out (the tell-tale criticisms were that Hendrix ‘was either asleep or thinking about his guitar’). The dismissal also meant that Hendrix was ineligible for combat when Vietnam reared its ugly head three years later; his work, however, was to be of considerable comfort to soldiers stationed there over the coming months. Hunting out the R & B scene in nearby Nashville, Hendrix moved there to play alongside heroes like Curtis Knight – the man generally accepted to have discovered Hendrix – and Little Richard.

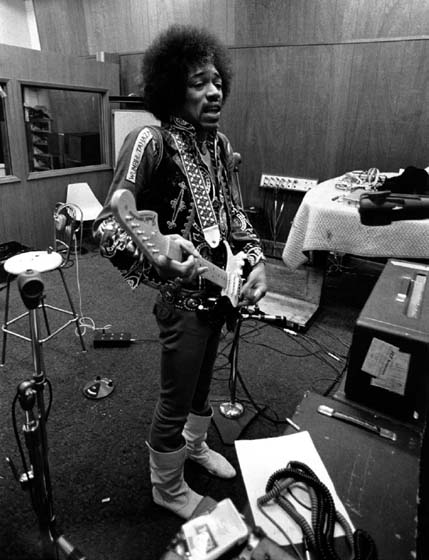

Jimi Hendrix: In the studio, and out of it

‘He was tryin’ to spread a little joy and love to his people. Cocaine, grass, heroin? Jimi was gonna take ‘em higher than that!’

Close friend and colleague Little Richard

Just ahead of his twenty-third birthday, Hendrix signed a three-year contract with Ed Chalpin that was later to cause him problems. As Jimmy James & The Blue Flames (originally The Rainflowers), Hendrix and his band – which featured a young Randy California, later of rock band Spirit – gained a residency at New York’s Café Wha?, a Greenwich Village venue where his talent was at last likely to be unearthed by musicians who had the means to make a difference. Via a tip-off from Linda Keith (Rolling Stone Keith Richards’s girlfriend), Hendrix met Animals bassist Chas Chandler, who offered him the chance to record ‘Hey Joe’, a song coincidentally already in the guitarist’s oeuvre. Back in London – where Hendrix was to make his name first – word spread quickly among the heavyweights of rock and blues about this freaky US prodigy: a ‘table napkin’ deal was duly signed with Kit Lambert’s Track label. Before ‘Hey Joe’ (1966) became a UK Top Ten hit, a jam session saw Hendrix wipe the floor with Eric Clapton; the Cream legend was initially nonplussed and muttered to his bandmates: ‘You never told me he was

this

fucking good!’ And Clapton was to be trumped once again – just a few months later, The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s debut album,

Are You Experienced?

(1967), blew Cream’s

Disraeli Gears

clean out of sight in Britain. In the States, the ride was not to be quite so smooth: on tour with fans The Monkees, Hendrix was heckled off stage, but, as a live act, The Experience were unlike anything rock ‘n’ roll had yet seen – and certainly

not

intended for teenyboppers. The stoic Noel Redding (bass) played straight man to the crazed antics of drummer Mitch Mitchell and, of course, the man at the centre of the fire. But, despite the mythologizing, Hendrix only performed the ‘flaming guitar’ trick three times, most famously at Monterey in 1967 – for many, the summit of Hendrix’s live achievements.

Following this triumphant period there was inevitably a backlash; suffice to say, it began around mid 1967 and never let up. If the resurfacing of the Chalpin contract (about which Lambert and Chandler knew nothing) was one small problem, the increased presence of drugs in Hendrix’s daily routine was a greater one. Although he was a very likeable, unassuming person in the main, Hendrix soon revealed that he had much rage lurking within him. After a fraught tour of Scandinavia, the frontman fell out with the somewhat disapproving Redding, losing his temper, trashing a hotel room and getting himself busted for the first time. Things weren’t much better back in London, either. Although most still found the music great – follow-up albums

Axis: Bold As Love

(1967) and the double

Electric Ladyland

(1968) were also astonishingly innovative – in the studio, Hendrix became more and more self-indulgent the more he used. Mentor and producer Chas Chandler finally quit when the guitarist was demanding as many as forty takes for a song and was still unsatisfied. A further split then occurred, from business partner Mike Jeffery, a man believed by many to have embezzled much of Hendrix’s money and to be linked to the Mafia.

In 1969, Hendrix’s infamously ‘arrogant’ appearance on BBC television’s

Happening For Lulu

show was followed by yet another highly publicized bust (heroin, this time) and a final split with Redding. Billy Cox took over bass in time for another landmark performance at Woodstock – the festival’s loose organization left Hendrix and his new band, Gypsy Sun & Rainbows, playing to just 30,000 at 8 am on 18 August. Those who saw and heard the event witnessed something remarkable, however: Hendrix objected vehemently to the continued US presence in Vietnam, but instead of voicing his disapproval – as many had in the days preceding – he treated the audience to the most surreal, distorted version of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ on his prized Strat. Rumours persist that he had been spiked with powerful acid just ahead of the gig; whether this was or was not the case, it proved a chilling precursor to the sad, final events of the following year.

With Mitch Mitchell also gone, Hendrix began another shortlived project, The Band of Gypsys, with old pal Buddy Miles on drums; despite a memorable New Year gig at Fillmore East (documented on his last authorized album, issued in May 1970), they too went the way of all flesh before the end of January 1970. Although Mitchell returned to the fold, a European tour folded because Cox suffered a breakdown. Time, it seemed, was all but up. On the back of these problems, plus a commercial direction he felt was stifling his creativity, Hendrix began snorting heroin that summer. One of the last to see Jimi Hendrix alive was The Move’s Trevor Burton, who described the star as ‘out of it, with no one to look out for him’: this appeared to be the case on 18 September. Monika Dannemann, an obsessive German ‘fan’ who had become more than just an acquaintance to Hendrix, had given him a handful of Vesperax sleeping pills,

nine

of which he foolishly ingested, with alcohol. The story from hereon is confused. Dannemann maintained for many years that Hendrix was still alive when she accompanied him in the ambulance to hospital – a claim refuted by another of the star’s noted affiliates, Kathy Etchingham, who started legal action against Dannemann in the nineties. (As a result, the distraught Danneman committed suicide in 1996.) Police arriving at London’s Samarkand Hotel the following morning definitely found Hendrix alone, lying dead in a pool of his own vomit. Perhaps the greatest musical talent of his generation was gone, in the saddest, most squalid way, the circumstances of which have been the subject of endless conjecture in the decades since, taking in suicide, medical incompetence – and even murder. But Jimi Hendrix was far from the drug-crazed control freak that some would have him, more a sensitive, misguided soul frustrated and finally slain by the myth that had been encircling him for some time – when all he wanted to do was play.

Hendrix was interred in Renton, Washington; friends held an impromptu jam session beside the open casket at his wake. In the UK, Hendrix became the latest posthumous chart-topper when his ‘Voodoo Chile’ went to number one two months after his death. Hendrix’s estate, estimated at $80 million, was at the centre of an unseemly court battle: the singer’s brothers – left out of the will – failed to secure any of the estate after Al Hendrix’s death in 2002. Indeed, no relative on his mother’s side has ever benefited, individuals unable even to agree where his casket rests, it having been ‘moved’ by his sister that year.

See also

Chas Chandler ( July 1996); Randy California (

July 1996); Randy California ( January 1997); Noel Redding (

January 1997); Noel Redding ( May 2003); Mitch Mitchell (

May 2003); Mitch Mitchell ( November 2008); Moogy Klingman (

November 2008); Moogy Klingman ( November 2011)’. Hendrix’s King Casuals replacement, blues guitarist Johnny Jones, died in 2009.

November 2011)’. Hendrix’s King Casuals replacement, blues guitarist Johnny Jones, died in 2009.