The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (24 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

10 ‘I Want My Baby Back’

Jimmy Cross (1965)

Finally, a crude but nonetheless amusing 1965 pastiche of the death-ditty genre that saw its lead attempt to reunite with his dead girlfriend by jemmying open her coffin. The pair had crashed on the way home from a Beatles gig; Cross’s baby was found ‘over there’ and ‘over there’ and ‘over there’ - you get the idea. The record’s most notable airing was as chart-topper of Kenny Everett’s Capital Radio

Bottom Thirty

(a hilarious ‘worst records’ countdown) more than a decade after issue.

1971

MARCH

Saturday 13

Arlester ‘Dyke’ Christian

(Buffalo, New York, 13 June 1943)

Dyke & The Blazers

(The Odd Squad)

‘Funky Broadway’ – as chunky a piece of New York soul as could be found in 1967 – was the catalyst record for the brief notoriety of Arlester ‘Dyke’ Christian’s band, Dyke & The Blazers, the East Side’s prime funk unit at the end of the sixties. When discovered, ‘Dyke’ Christian was merely a beanpole street-gang kid who somehow just had the brass neck to carry it all off. Under the guidance of mastermind Carl La Rue, Dyke & The Blazers stormed the chitlin circuit (New York’s soul- and sleaze-loving clubs and bars), and with the steamy ‘We Got Soul’ and the of-its-time ‘Let a Woman be a Woman, Let a Man be a Man’ even managed a brace of national Top Forty hits in 1969. But Christian’s street habits were hard to kick: though he had purchased a ranch house in Phoenix, he’d often be found hanging out or gambling with acquaintances from those days – and would in time develop something of a heroin dependency. Eventually, this caused the indirect dissolution of The Blazers.

Just ahead of a European tour with a new band, The Odd Squad, Arlester Christian found himself back on Broadway (Phoenix, this time) – and somehow in a disagreement with a man named Clarence Daniels. Rumour had it that Christian believed this man to be a police nark, though more likely he was a dealer to whom the soul man owed a lot of money. As their debate became more and more heated, Christian grabbed Daniels through the window of his 1963 Falcon; the driver then pulled a pistol, shooting the singer twice in the chest, once in the thigh and once in the temple. Arlester Christian was pronounced dead at around 3 pm. Despite the ferocity of Daniels’s shooting, the gunman was acquitted of all charges that December, having ‘acted in self-defence’.

JULY

Saturday 3

Jim Morrison

(Melbourne, Florida, 8 December 1943)

The Doors

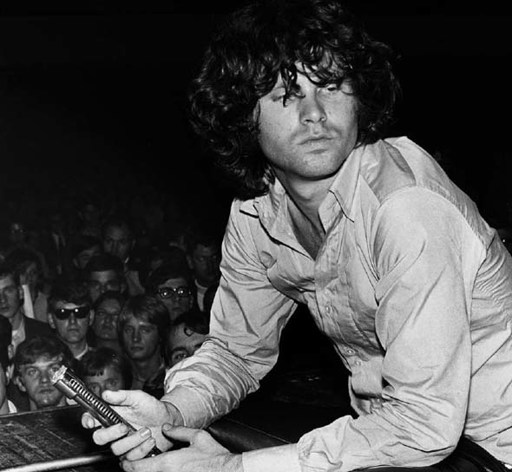

Jim Morrison: Back off, cop - it’s just a microphone

From the lithe, barefoot nomad walking California’s beaches to the ravaged figure found in his Paris bathtub just six years later, Jim Morrison was the complete artist. He wore rebellion as a badge, was obsessed with chaos and disorder, urgently compelled to push it all just that one stage further. Morrison was wilful, selfish and goading – yet at times the self-styled ‘Lizard King’ displayed deep integrity, warmth, no small love for others and a knowledge of what they had to offer. Morrison’s unusual death only compounded a legend already close to fully grown.

Born into a military family that insisted upon achievement through strict discipline, James Douglas Morrison was a war baby; his father, Steve – who was to become the youngest admiral in the US navy – was away much of the time. Morrison’s father disapproved of his son’s diametrically opposed ideals, and the boy drifted away, never to return to the family fold. Indeed, as The Doors hit their stride and his mother, Clara, and brother, Andy, attempted to see the estranged star after a Washington concert, Morrison openly snubbed them. Morrison’s world was his and his only, but even before fame allowed him the luxury of picking and choosing companions, he was making this kind of decision as a matter of course.

Much, however, has been made of one particular family experience spoken of by the singer. As a 4-year-old, Morrison travelled with his family from Santa Fe to Albuquerque (one of many addresses he knew growing up). On the journey, their car encountered an overturned truck and a group of injured and dying Pueblo Native Americans. Morrison was overwhelmed by the harrowing spectacle, claiming that the soul of one of the dead Pueblos had passed into his body at that moment. He believed that this event above all others gifted him his freedom of spirit, his desire to reach inside the soul and his urge to spread the values he felt were as essential as they were inflammatory. As a student at Florida State University, Morrison read Nietzsche, Rousseau and Sartre – though the texts that perhaps fired his imagination the most were those of French surrealist Antonin Artaud (who believed in the cathartic purification of man through adversity) and Norman O Brown, whose

Life Against Death

inspired Morrison with its Freudian reinterpretation of history as the result of man’s hostility to life. Morrison believed one had to stretch one’s own personal boundaries and to reject authority without qualm. His method of getting himself to the abyss was through his poetry and his performances, certainly – but the combined assistance of mind-altering substances and no shortage of people to help him indulge his every whim greatly hastened this achievement.

The name of his ground-break-ing band came via two other Morrison gurus: borrowing from a William Blake couplet, writer Aldous Huxley called the account of his own drug experiences

The Doors of Perception.

This title gave Morrison a tag; he was after all, already a big hash-consumer and had experimented with hallucinogens. One of the friends he had made at UCLA while studying film was musician Ray Manzarek; the keyboard-player was bowled over by the intensity of this wayward spirit and his no-holds-barred poetry when Morrison knelt before him on Venice Beach spilling what would become ‘Moonlight Drive’. Manzarek introduced Morrison to guitarist Robby Krieger and drummer John Densmore (of The Psychedelic Rangers). Bar mitzvahs and party shows became gigs at local bars, these giving way to a residence at the Whisky A Go-Go, the fabled venue on Sunset Boulevard, in 1966 just a year or two old itself. The Doors, as Morrison had desired, were well and truly ‘open’. But this was no one-man show: the singer himself made it apparent to anyone who would listen that although he may have been the focal point The Doors were very much ‘a group’. Manzarek was to prove a versatile keyboardist who drew inspiration from jazz and dance styles (the opening salvo of ‘Break On Through’ is pure bossa nova), while Krieger pretty much wrote early Doors’ classic ‘Light My Fire’ on his own, and Densmore was an able pianist as well as percussionist. (Nevertheless, Manzarak and Krieger were to lose a legal battle with Morrison’s family over use of the band name after they unveiled a new line-up – with former Cult vocalist Ian Astbury – three decades after the original singer’s death.)

However, it was Morrison’s stage antics that were most talked about by The Doors’ increasing following. Relations were ‘up and down’ at the Whisky, where the singer often performed drunk – occasionally with his back to the crowd. But Elektra saw the potential in this extraordinary shaman who dominated the stage with three decidedly leftfield-looking musicians improvising around him. By 1967, The Doors were dubbed America’s Rolling Stones, though this band was to add a dimension of ‘art academia’ to the familiar pattern of sleaze-soaked rhythm and blues. As first album

The Doors

began to climb the charts (the sleeve notes claimed his family were ‘dead’), Morrison was courted by the press, who found the ‘erotic politician’ (his words) good for a quote. Produced by the highly rated Paul Rothchild, this debut eventually hit number two across the USA, selling a million copies in the process. Its second single, ‘Light My Fire’, went to Billboard number one in July 1967 (a trick they pulled off a second time with ‘Hello, I Love You’ the following summer). As unlikely as it seemed, Los Angeles’ most uncompromising band were now stars; Morrison marked the occasion by getting royally drunk and buying the tightest black-leather outfit in California, but his apparent disaffection with pop stardom was already evident as Doors-mania caught on around him like a forest fire. The one saving grace of fame, as he saw it, was the extended opportunity to antagonize authority (‘I am the Lizard King – I can do anything!’). His disregard of TV host Ed Sullivan’s wishes by singing the banned word ‘higher’ (in ‘Light My Fire’) on his show is just one example, the regular goading of officers at The Doors’ by-now heavily policed concerts another. And more was to follow.

‘If you can get a whole roomful of drunk, stoned people to actually wake up and think, you’re doing something.’ This was the thrust of much of Morrison’s rhetoric over the years. It may well have been the case, but by 1969 Morrison was almost perpetually ‘gone’ himself: his indulgences hit previously unseen heights and studio sessions were wasteful; performances, similarly, started to descend into mayhem. To Morrison, though, this was all part of the deal, and a March concert in Florida proved a pivotal point in his career. He had been ‘inspired’ by recent performances of Artaud’s work involving chaos and public nudity. He had also been drinking heavily on the flight to Miami, and, like the rest of The Doors, was angered by the venue’s attempts to take money from them. As his rapidly wearying band started up the strains of ‘Touch Me’, Morrison apparently decided to take his own lyric a shade literally. Whirling drunkenly about the stage, Morrison taunted his audience – ‘You’re all a bunch of fuckin’ idiots! How long you gonna be pushed around?’ – who lapped it up regardless. Then, in one of rock’s most infamous incidents, he tantalized the crowd further by offering to reveal his genitals. Whether he actually did this or not has never been ascertained; although he was arrested soon after the performance, the trial lasted a year and a half and Morrison was eventually sentenced to a total of eight months’ hard labour and a $500 fine. Of course, he didn’t live long enough to endure this punishment.

After the drawn-out trial, Jim Morrison decided The Doors’ sixth studio album

(LA Woman,

1971) was to be his last with the band. He was tired of the circus of which he’d long been ringmaster and wished to devote his time to other media projects – in particular his resonant, lurid poetry, which had already gained favourable attention. Morrison and his long-term, on-off partner, Pamela Courson (who’d adopted his name early on), moved to Paris in March. Here, the couple seemed at ease, the pressures of fame and the law, as well as their continued infidelity to one another back in California, diminishing with the late-afternoon sunlight as it played on the Seine. Sometimes they lived at the hotel where another Morrison hero, Oscar Wilde, had died – at others in an apartment at 17 rue Beautreillis.