The End of Power (45 page)

Authors: Moises Naim

In short, disruptive innovation has not arrived in politics, government, and political participation.

But it will. We are on the verge of a revolutionary wave of positive political and institutional innovations. As this book has shown, power is changing in so many arenas that it will be impossible to avoid important transformations in the way humanity organizes itself to make the decisions it needs to survive and progress. This kind of surge in radical and positive innovations in government has happened before. Greek democracy and the wave of political innovations unleashed by the French Revolution are just two of the best-known examples. We're overdue for another. As the historian Henry Steele Commager asserted about the eighteenth century:

We invented practically every major political institution which we have, and we have invented none since. We invented the political party and democracy and representative government. We invented the first independent judiciary in history. . . . We invented judicial review. We invented the superiority of the civil over the military power. We invented freedom of religion, freedom of speech, the Bill of Rightsâwell, we could go on and on. . . . Quite a heritage. But what have we invented since of comparable importance?

9

After World War II, we did experience another surge of political innovations designed to avert another global conflict. That led to the creation of the United Nations, and to a plethora of specialized international agencies such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund that changed the world's institutional landscape.

ANOTHER, EVEN MORE SWEEPING, WAVE OF INNOVATIONS IS BUILDING,

one that promises to change the world as much as the technological revolutions of the last two decades did. It will not be top-down, orderly, or quick, the product of summits or meetings, but messy, sprawling, and in fits and starts. Yet it is inevitable. Driven by the transformation in the acquisition, use, and retention of power, humanity must, and will, find new ways of governing itself.

PPENDIX

Democracy and Political Power:

Main Trends During the Postwar Period

Note to readers:

This appendixâprepared by Mario Chacón, PhD, Yale Universityâapplies particularly to

Chapter 5

.

EASURING THE

E

VOLUTION OF

D

EMOCRACY AND

D

ICTATORSHIP

I start by taking a look at how the number of democratic regimes has changed over the last four decades. To determine which countries are democracies and which ones are not, I have used two taxonomies widely employed in the academic literature.

The first taxonomy of regimes is the one provided in the

Freedom in the World

survey conducted by Freedom House (2008). In this survey, regimes are classified as “not free,” “partially free,” and “free.” Each country is classified depending on a scale that measures political rights and civil liberties. The subcategories measured in the scale are freedom of electoral processes, political pluralism, functioning of government, freedom of expression and belief, associational and organizational freedom, rule of law, and personal rights. For purposes of the analysis, I categorize “free” countries as full democracies, and “not free” and “partially free” countries as nondemocratic.

The second source I used is the regime classification of Przeworski et al. (2000), which is based on a minimalist definition of democracy similar to the one proposed by Schumpeter (1964). In this classification, a “democracy” is a regime in which the government is selected through contested elections. Thus, in this classification free and fair contestation is the fundamental facet in any democratic regime (see Dahl 1971 for a similar approach). Using these two classifications, I have calculated the percentage of all independent regimes in the world that are classified as “democratic” (as opposed to “nondemocratic”) in any given year.

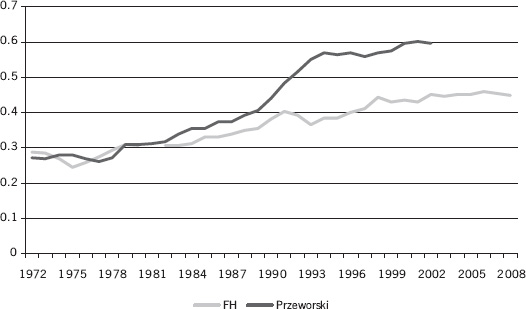

Figure A.1 shows the evolution of democratic regimes worldwide since 1972.

*

F

IGURE

A.1. P

ERCENTAGE OF

D

EMOCRATIC

R

EGIMES

: 1972â2008

Â

SOURCE:

Adapted from Freedom House Index.

As shown in

Figure A.1

, the percentage of democracies across the world has increased significantly in the last four decades. According to Freedom House, in 1972 a little more than 28 percent of the 140 independent regimes observed in the world were democratic. Thirty years later, in 2002, this figure was 45 percent. This global increase in the number of democracies is confirmed by Przeworski's data. In this classification, between 1972 and 2002 the percentage of democracies increased from 27 percent in 1972 to 59 percent in 2002. The differences between the two measures are to be expected given that the conditions for democracy used by Freedom House are somewhat stricter than the ones used by Przeworski and his coauthors. Yet, we can conclude from this first approximation that there has been an overall positive trend in the number of democratic regimes around the world in the past three decades.

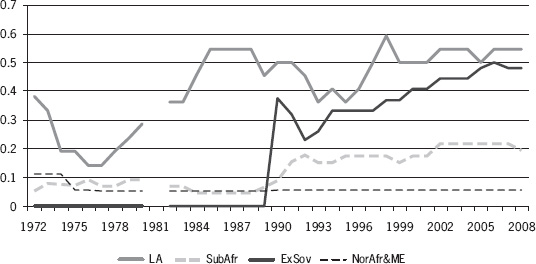

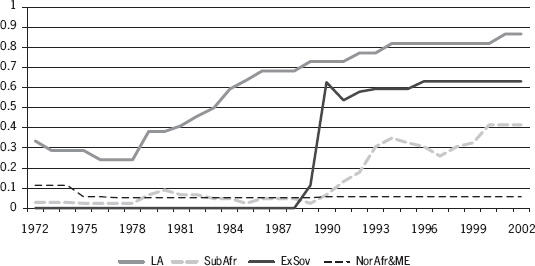

Are there regional differences in the evolution of democratic regimes? If the factors causing drastic regime changes are clustered across space, we should observe regional patterns in the evolution of democratic regimes. These regional patterns are closely related to the idea of “waves of democratization” described originally by

Huntington (1991). To explore this possibility, in Figures A.2 and A.3 I show the evolution of democratic regimes (as a percentage of all the regimes) in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, the ex-Soviet bloc, North Africa, and the Middle East.

*

As shown in these two figures, many Latin American and ex-Soviet countries experienced a democratic transition during the period from 1975 to 1995. These transitions occurred mostly in the late 1970s for Latin America and in the early 1990s for the ex-Soviet bloc (following the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989). In 2008, 54 and 48 percent of the Latin American and ex-Soviet countries, respectively, are classified as free (democratic) by Freedom House. There is also a positive trend in democratization in sub-Saharan Africa, although it is less steep than the trend for Latin America. The Arab countries of North Africa and the Middle East are remarkably stable, and fewer than 10 percent of them are classified as democracies throughout these years. These patterns are confirmed by Przeworski's data, which are graphically represented in

Figure A.3

.

These trends, of course, do not yet capture the effect of the Arab Spring on the political regimes in North Africa and the Middle East.

F

IGURE

A.2. R

EGIONAL

T

RENDS

(F

REEDOM

H

OUSE

2010)

Â

SOURCE:

Adapted from Freedom House,

Freedom in the World: Political Rights and Civil Liberties 1970â2008

(New York: Freedom House, 2010).

The OECD countries are not shown because these countries did not experience any radical regime change during the period in question. Given that all of these countries were democratic at the beginning of the period studied, their evolution is characterized by a stable (consolidated) democracy.

F

IGURE

A.3. R

EGIONAL

T

RENDS IN

D

EMOCRACY

(P

RZEWORSKI ET AL

., 2000)

Â

SOURCE:

Adapted from A. Przeworski, M. Alvarez, J. A. Cheibub, and F. Limongi. 2000.

Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950â1990

, Cambridge University Press, New York.

INOR

R

EFORMS AND

L

IBERALIZATIONS

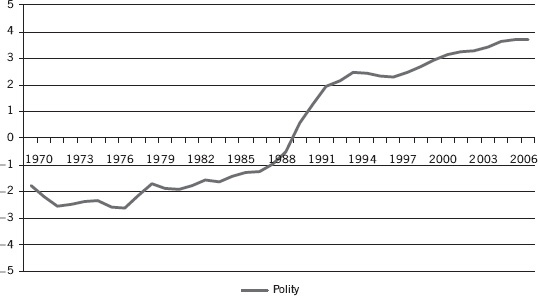

The figures presented thus far focus on radical political transformations in which a political regime becomes (or ceases) to be a democracy. These numbers may hide smaller movements toward democracy in many countries that did not experience a full transition. Minor reforms may induce important changes in the distribution of political power and human rights. For instance, many nondemocratic regimes introduced and allowed electoral competition to elect the legislature and high executive positions. Even if most of the elections in regimes considered fully democratic are not completely fair, minor liberalization may signal important changes in the distribution of power. Moreover, many transitions occur gradually, so the initiation of electoral competition may be indicative of future democratizations.

To explore minor reforms, I have employed the

Polity Score

developed in the Polity Project of Marshall and Jaggers (2004). This measure is a continuous approximation that allows us to capture smaller regime changes, whether or not they end in democratization. Specifically, the Polity Score is a 20-point scale (ranging from â20, for a full autocracy, to 20, the score of a full democracy) measuring various facets of democracy and autocracy. The components of the scale include competitiveness and openness of the executive recruitment, constraint on the executive, and competitiveness of political participation.

Figure A.4

presents the evolution of the world average Polity Score.

F

IGURE

A.4. E

VOLUTION OF

D

EMOCRACY

: 1970â2008

Â

SOURCE:

Adapted from Monty Marshall, K. Jaggers, and T. R. Gurr, 2010. Polity IV Project, “Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800â2010,”

http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity4.htm

.