The Essential Book of Fermentation (26 page)

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

In a final example, out of many, many more: “Wine strains of

Saccharomyces

producing bacteriocins have also been constructed,” according to Professor Bisson. “Bacteriocin production by yeast strains offers many advantages over the current practice of use of sulfur dioxide.” In other words, genetically engineer a strain of killer yeast that will knock out all diversity in the must, save for itself.

So what’s wrong with tinkering with the genetic control panels in yeasts to make them do what we want them to do?

Plenty.

It must be realized that naturally occurring genes represent a series of choices made over millions of years through natural selection, with nature’s overriding concern for the preservation of life. Each organism, large or small, is a whole system, with an integrity made up of a maze of complicated interactions with its environment. It’s genetically structured for optimization of its survival. It has an ecological niche that represents its place and its job in the interwoven web of life. It’s a cog in the gears of life on earth. With genetic engineering, human beings have found their way into the control room of life, and we are—as you would expect from primates like us—monkeying around. We’re pulling levers and pushing buttons, just to see what will happen. Sooner or later, we will modify a gene that will become a rogue in the environment (it has already happened with the release of Bt corn pollen into the farmlands of the world). If someone asked me what will life be like a hundred years from now, I’d have to say that humanity will be spending an enormous amount of resources tracking down and eliminating rogue genes, with catastrophic impacts on the environment and the natural ecology as we do so.

“The genie is already out of the bottle,” said Neil E. Harl, a professor of agriculture and economics at Iowa State University, speaking of GMOs. “If the policy tomorrow was that we were going to eradicate GMOs, this would be a very long process. It would take years, if not decades, to do that.”

A Visit to a Small Winery

In 1972, I made my first batch of wine, from grapes being thrown out of a local grocery store because they were too old. “Oh,” I said to myself in my ignorance, “I’ll make wine from them,” and took them home. I tried to make wine using bread yeast, which didn’t work very well. The wine was undrinkable. I poured it out. Then I tried buying grapes from California, shipped to the New York area by rail. They were crushed into forty-pound boxes and were already turning to vinegar. Then I realized that it takes fresh grapes to make good wine. So I planted a small vineyard, mostly Chancellor, a French-American hybrid that could withstand Pennsylvania’s tough winters. The wine wasn’t bad, but it wasn’t world class. I decided to move to Sonoma County in the Northern California wine country.

A month after my transcontinental move, I ran into a group of guys who made garage wine. Tasting it, I saw right away that they made it right, from great grapes, using French oak barrels. One of the fellows was moving away, and so a spot in the four-member group opened up for me.

Soon I found myself high on Sonoma Mountain in Dave Steiner’s Cabernet Sauvignon vineyard, helping to select and pick grapes. Some of the grapes had a vegetal flavor, like asparagus, that signaled they were not ripe and probably would never become fine wine. Other grapes in a sunnier location tasted wonderful—clean, fresh, bursting with fruit flavors. So we convinced Steiner to sell us a ton of the clean-tasting fruit that we selected from various parts of the vineyard. Because he knew our wine (the group had been making it from his grapes for years before I showed up) and thought it was as good as if not better than any of the commercial wineries that bought his grapes, he agreed. And all we wanted was a ton—the production of about two hundred vines out of the many thousands in his twelve acres of vines. We filled two half-ton fermenters—open-topped plastic tubs four by four feet square, about three feet deep, slipped into wooden frames to support them and loaded onto the bed of a pickup truck amid a cloud of yellow jackets, which follow the grape gondolas in wine country like camp followers after Caesar’s legions. “A few yellow jackets in the wine are a quality point,” we’d say.

Back at the garage we used as a winery, we picked through the grape clusters to reject any rotten or green berries, and tossed the ripe bunches into a stemmer-crusher. This small electric motor-driven machine sat on two boards laid across the top of an empty half-ton fermenter. Greenish-brown grape stems came twisting out of the end, while lightly crushed grapes fell into the vats below. When the grapes were all crushed, we covered them with a piece of plastic sheeting to keep out the fruit flies (fruit flies carry

Acetobacter

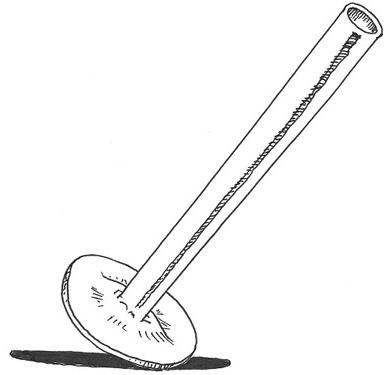

bacteria that make vinegar, not wine) and went home for a day. Allowing the must to sit uninoculated for a day is called a cold soak and is very beneficial to the finished product. The next day, we stirred two ounces of dried wine yeast (originally we used Montrachet yeast, but later changed to the gentler-acting Prix de Mousse) into a jar of the grape juice in the fermenters and gave the yeast time to dissolve and wake up. Then we poured half the jar into each fermenter. Before going home, we punched down the cap. Punching down has to be done at least twice a day. Grape skins float, and if left alone, they’ll become a breeding ground for spoilage organisms. Punching down submerges the cap of grape skins under the surface of the must, wetting them and keeping them moist. For our punching-down tool, we used a flat metal stainless-steel plate we’d welded to the end of a stainless-steel pipe.

Twice a day (or more often if we were nearby) we’d take turns visiting the garage, removing the plastic, punching down the cap, and replacing the plastic. Within three days, the vats came to a rapid boil. The sweet, yeasty aroma of the fermenting must greeted us as we walked up the driveway to the garage. Fruit flies began to multiply, but only a few could reach the must, and a few aren’t really a problem. “A few fruit flies are a quality point,” we’d say.

After about four days, we’d inoculate the must with

Oenococcus oeni

, the malolactic bacteria. The malolactic fermentation softens the harsh acidity of the wine, and if not done during the primary yeast fermentation, can happen spontaneously later on, even when the wine is in the bottle. When that happens, the corks get pushed out and the wine spoils, so we always made sure the must went through malo at the end of the primary fermentation. After five or six days, the must would cease its vigorous seething and quit working. A hydrometer showed us whether the fermentation was finished—when all the sugar is changed to alcohol, it gives a negative reading. Even though the fermentation was over, we still had to punch down the cap. But because clouds of carbon dioxide were no longer boiling off the surface of the must, preventing the fruit flies from entering, we knew the vats needed added protection. So we bought two tanks of commercial carbon dioxide and ran clear plastic hose from the tank valves to the plastic sheets, punched little holes in the sheets, and inserted the hose into the holes. Then we’d open the valve just a crack so a barely audible amount of gas could escape and reach the vats, keeping a protective blanket of carbon dioxide over the must. At this stage, too much air reaching the must can cause the alcohol to transform once again—this time to vinegar. By keeping the must away from air, the process stops at alcohol—at wine, that is, for that is what the liquid in the vats had now become. We’d try a sip, but it was usually chalky with yeast and not very appealing at this young stage.

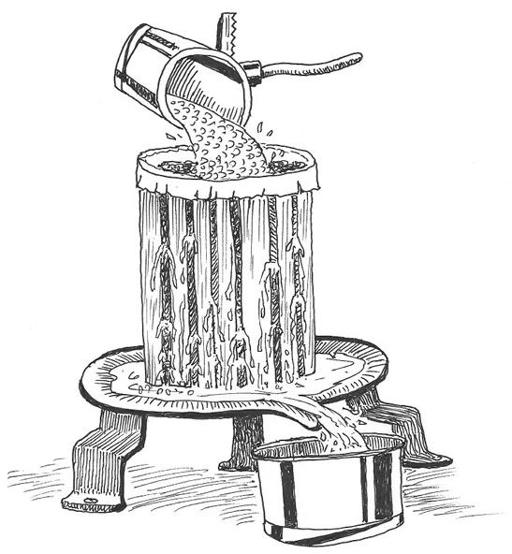

After about three weeks, the cap of skins had yielded up all they could give to the wine, becoming paper thin and sinking through the liquid. That was our signal to press the new wine off the skins. We had a big hand-operated basket press that we’d line with a porous mesh plastic bag. We scooped up buckets full of must from the fermenting vats and poured them into the bag. Free-run juice would pour out onto the press’s platelike platform, then through a spout into clean buckets. When a bucket filled with wine, we’d carry it to a barrel and pour it in using a big, wide funnel. When the mesh bag was full of sopping wet skins, we’d slip the ratchet-operated follower onto the center spline, insert the long metal handle, and work it back and forth. Each back-and-forth motion produced a satisfying click-clack, and screwed the follower another click down onto the bag full of juicy skins. It took about five minutes to press the bag firmly enough to get out most of the wine. Then we’d remove the follower, empty the bag, reinsert the bag in the basket, and start pouring in more buckets of new wine. In this way, we soon filled two sixty-gallon French oak barrels with our young wine. The bungs on top of the barrels can be fitted with airlocks if the wine is still fizzing (airlocks allow gas out but no air back in) or with silicone stoppers that fit snugly in the bung holes. Since we did an extended maceration of about twenty-eight days, the wine was completely dry (all the sugar fermented) and so we generally used the silicone bungs. After cleaning up, our work was done for the day. It was usually about late October to mid-November when we pressed the wine off the skins.

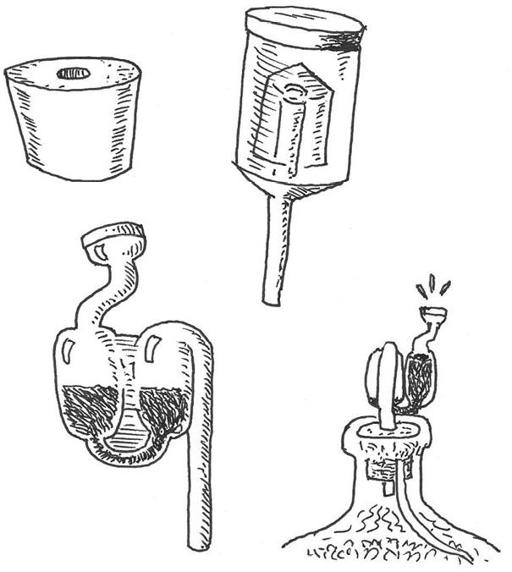

Clockwise from top left: Bung with center hole to accept an airlock. Two-piece plastic airlock. Airlock set-up on a five-gallon carboy. One-piece plastic airlock showing proper fill of water.

By late November or the first week in December, we’d rack the wine off the gross lees. This means that we’d pump the wine from the barrels into large plastic containers until we saw the chalky lumpy residue that had accumulated in the bottom of the barrels start to enter the clear plastic hoses attached to our pump. At that point, we’d carry the barrels outside and turn them bung hole down so all the gunk would run out, then wash them out thoroughly with a hose and return them to their places in the garage. Then we’d pump the wine from the containers back into the barrels. The wine gets a good aeration during a racking, which helps clarify it and is quite beneficial. But once back in the barrel, the wine is kept away from any contact with air, which encourages spoilage organisms to grow. The Cabernet starts tasting pretty good at this stage, and we always made sure to taste a quantity of it as we worked.

Two more rackings, around the first of the year and again in March, removed any more sediment. We never filtered our wine (never needed to) and never fined it. Fining is a process that clarifies wine that may be a mite cloudy. But it also strips some flavor and color components from the wine. Our wine always became perfectly clear by the third racking.

After that, the wine remained in the barrel for another year. The only job was to give it a small dose of sulfites to protect it, and occasionally take out the silicone bung and top it up with wine so there was no air space inside. When the wine was almost two years old, usually in August or early September, it was time to bottle, which would not only get the wine off the oak (as time in barrel is called), but would free up the barrels for the wine that would be made that fall. Each year we’d discard the oldest barrel and replace it with one new French oak barrel. That gave us a new barrel and a year-old barrel to age each vintage of our wine. All new oak might make the wine too oaky. All old barrels might not imbue the wine with enough of the subtle flavors and aromas that oak gives. Having one new and one old barrel was perfect, but we made sure that all the wine was blended together before bottling so that the wine that had spent the year in new oak would be mixed with the old oak wine, balancing the flavors.