The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice (38 page)

Authors: Patricia Bell-Scott

Tags: #Political, #Lgbt, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #20th Century

The next morning, Pauli and Bonnie were roused by a knock at their bedroom door and the appearance of a pink-faced “

apparition” framed by a “

towel-turbaned” head. It was ER, offering a practical suggestion. “

There’s a swimming pool around by John’s house and nobody uses it this time of year,” she said. “I just came back. I took my soap and towel down with me, rubbed myself all over with the soap, looked up and down the road to see that nobody was coming, and I just went right down in the pool and took my bath. If you hurry, you can do the same. Just be sure nobody’s looking.”

Murray and her niece were incredulous. What would happen if the neighbors, who included the Vanderbilts and Morgenthaus, saw two unfamiliar black women bathing in the

Roosevelt family pool? Too shamefaced to admit how nervous ER’s proposal made them, Murray and Bonnie donned their robes, gathered soap and towels, and slunk toward the pool.

Their hope of going unnoticed was dashed when ER’s daughter-in-law Anne “

came out and stared” at them “in utter bewilderment.” They explained that they were following ER’s instructions, whereupon Anne led them to the pool, and the family’s large dog happily joined them. No sooner had they dipped their toes into the water than they spotted a delivery truck coming toward them. They scurried back to the cottage and were relieved to find the lights and hot water restored.

Later, over lunch, everyone chuckled at seven-year-old

Sally Roosevelt’s tale of seeing Grandmère bathe in the swimming pool and Anne’s account of the confused, bathrobed strangers wandering through her backyard. Murray would never forget “

what a wonderful weekend it was.”

41

“You Might…Comment from the Special Woman’s Angle”

A

fter her

Val-Kill visit, Pauli Murray learned that her editor “

was very disturbed at the direction the

book had taken.” This was troubling news, yet Murray was not surprised. She knew that “

something was wrong, but could not pinpoint the problem. It seems,” she told her friend Caroline

Ware, “that I got bogged down with factual and historical material, and had my characters in the background instead of the foreground.” Having identified the problem, Murray started over, rising every day at four and working until noon. Her family soon emerged center stage in the narrative.

Rewriting so consumed Murray that she did not contact Eleanor Roosevelt for a year. By the time Murray wrote to ER, her editor had approved the first half of the book, and the

Housing and Home Finance Agency had dismissed Corienne

Morrow and her supervisor,

Frank Horne. Of the agency’s nine hundred employees, Morrow and Horne were among the highest-ranking of the small number of blacks. Clearly, they had been singled out. Although agency officials gave “

budgetary considerations” as justification for this action, civil rights leaders charged that the real goal was to remove two capable,

Democratic advocates of housing integration from the federal government. (

Morrow and Horne were replaced by two black

Republicans,

Joseph Ray, a real estate agent from Louisville, and

Joseph Rainey, a former magistrate from Philadelphia.)

Because Morrow was a woman and without Horne’s political connections, Murray forwarded a packet of background information to ER and a letter that said, “You might…comment from the special woman’s

angle.” Morrow was “

one of the top-level women in federal service” and among a handful of experts in “the complicated field of federally-aided

housing.” A role model for African Americans and women, she had worked her way up from an entry-grade secretarial job to a senior

civil service position. If she could be dismissed in violation of civil service guidelines after twenty-one years, Murray declared, “

the outlook is discouraging indeed.”

The firings angered ER. She was a longtime supporter of open and fair housing, and she detested political intimidation. She knew

Frank Horne from his work in the Negro Affairs Division of the

National Youth Administration. And thanks to Murray’s introduction, ER had a personal interest in Morrow as well.

Joining a chorus of critics, such as

Charles Abrams, an urban planner and anti-discrimination activist who claimed the firings were motivated by

Republican-affiliated real estate groups opposed to housing integration, ER spoke out in her

column. “

There are very few Negroes employed at their level and yet Negroes are among those needing better housing in almost every city in this country.” In view of the fact that HHFA funding had actually increased by approximately $2.8 million dollars, the “

budgetary reasons” officials gave seemed invalid and the dismissals “highly unfair.” ER reprimanded HHFA director Albert M. Cole and his staff for asking Congress “

to go slow” on integrated housing. “This should not be the policy in any national agency,” she insisted.

ER also put the spotlight on Morrow, closely paraphrasing Murray’s description of the situation:

Dr. Horne’s case is being publicly fought. Mrs. Morrow’s is just mentioned in passing now and then but it is of special interest to women because she worked her way up from a very low income bracket to an administrative position and she has been a symbol to many of her people both of the success and opportunity which Negro women might have in government service. She has almost 21 years of career service behind her and she is the senior in period service of all racial relations functionaries in the Housing and Home Finance Agency. Her annual salary was $10,065 when she was released. This makes her case important to a very great number of women, and I think should be brought to the public and followed very carefully.

Encouraged by ER’s advocacy, the

National Council of Negro Women and several civil rights groups took up Morrow’s cause.

The pressure

forced the commission’s hand. “

You’re a real darling,” Murray wrote to ER after Morrow’s reinstatement. “Among the many reasons why we love you—and we number billions—is your personal commitment to the many causes of humanity and the time you take with each cause whether it be one person or a nation.”

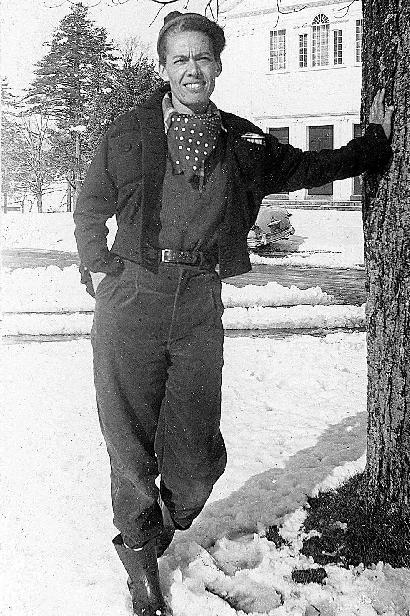

Pauli Murray takes a break at a rummage sale sponsored by a local Unitarian church in Hancock, New Hampshire, November 11, 1955. On the back of this snapshot, she wrote, “To Mrs. Roosevelt, with great affection.”

(Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library)

42

“I Cannot Afford to Be a Piker”

O

n October 26, 1955, Murray’s eighty-five-year-old adoptive mother,

Pauline Dame, died of a heart attack. Aunt Pauline had been the central maternal figure in Murray’s life since she was three. Murray was devastated by the loss, and the memory of her aunt’s final hours compounded her grief.

Murray had rushed home from The

MacDowell Colony in response to her aunt’s complaint of vision problems. To Murray’s surprise, Aunt

Pauline had prepared a

birthday meal even though Murray’s birthday, November 20, was three and a half weeks away. Her aunt seemed to sense that it would be their “

last ceremonial meal together.”

Before daybreak, Aunt Pauline developed chest pains and breathing difficulties. After trying unsuccessfully to reach her personal physician, Murray arranged for another doctor to come to the house. He relieved Aunt Pauline’s discomfort with medication and urged her to go immediately to a hospital. Murray soon discovered that no hospital would admit her aunt without her physician’s authorization, and Murray could not reach him until midmorning.

The next hurdle was getting an ambulance. In spite of Murray’s repeated calls, even with the doctor’s authorization, they waited for hours. Her worst fear surfaced when Aunt Pauline, gasping between breaths, murmured, “

I don’t think I’ll live to get to the hospital. I’ve got death rattles in my throat.”

The possibility that this beloved mother-aunt, who was a devout

Episcopalian, might die without a priest to deliver Holy Communion horrified Murray. She made a string of desperate calls to the church. Unable to reach a priest, she offered to read the

“Order for the Visitation of the Sick” from their well-used copy of

The Book of Common Prayer

. Aunt Pauline nodded her approval, and Murray began, slowly reciting “

the psalms and all the prayers,” replacing all masculine pronouns with the feminine form: “O Lord, look down from heaven, behold, visit, and relieve this thy servant…

defend her in all danger, and keep her in perpetual peace and safety.”

The ambulance finally arrived. As the attendants carried Aunt Pauline out of the house, she pointed to a hatbox that contained her “

burial undergarments.” Once in the hospital and resting comfortably, she sent Murray home, then “

slipped away peacefully” during the night.

Hearing the sacred text appeared to have consoled Aunt Pauline, yet Murray believed she had violated two family customs. One called for elders to lead their younger kin in prayer. The other called for priests, who were by definition male, to give the last rites. Murray felt that she had let her aunt down. Not having finished the family memoir intensified Murray’s sorrow.

Aunt Pauline was the third close relative of Murray’s to die in an eighteen-month period. Another maternal aunt,

Maria Fitzgerald Jeffers, and a paternal uncle,

Lewis Hamilton Murray, had passed earlier. These deaths and

Lillian Smith’s life-threatening illness deepened Murray’s

emotional reliance on Eleanor Roosevelt.

Murray steadied herself during the memorial service for Aunt Pauline with memories of ER’s

“fortitude” during

FDR’s

funeral.

After the burial, Murray divided the funeral spray ER sent into two bouquets, placing one bunch on Aunt Pauline’s grave and giving the other to a next-door neighbor whose wedding Aunt Pauline had planned to attend. Murray thought it appropriate that ER’s flowers grace her aunt’s grave site and the wedding festivities of a

family friend. ER

was

family and “

even more precious” now that so many elders were gone.

· · ·

EAGER TO RESUME WORK

on the memoir, Murray went to

Vassar College, in Poughkeepsie, New York, to confer with Lillian Smith and

Helen Lockwood. Smith was lecturing at Vassar and undergoing treatment at Memorial Hospital. Lockwood chaired the English Department. Both were enthusiastic about Murray’s writing, and the visit with them temporarily lifted her spirits.

During the drive back to the colony, Murray thought she glimpsed ER in the front seat of “

an Alice-blue colored car.” Fueled by the possibility of spending a moment in the presence of ER’s warmth, she “

chased” the vehicle until it disappeared on the

Saw Mill River Parkway. As Murray made her way to New Hampshire, alone and heavy of heart, she kept saying to herself, “

If Mrs. R. has the courage to do these things, I cannot afford to be a piker.” When she told ER about the car she had followed on her way back to New Hampshire, ER replied, “

You are very brave always so I think you have no need to fear.”

· · ·

MURRAY WAS RELIEVED

to be back at The MacDowell Colony, where the solitude and the natural beauty of the terrain comforted her.

As she walked the well-worn paths of former and current colonists, she paused periodically to bask in a stand of pine or a maple grove and to admire the ever-present deer, birds, chipmunks, and squirrels. This communion with nature and the desire to honor Aunt Pauline’s life renewed Murray’s determination to finish

Proud Shoes

. She plunged into the manuscript. She also began reading a biography of

Susan B. Anthony that deepened her connection to the “

marvelous tradition” of

feminist activism.

Two weeks after her aunt’s death, Murray posed for a “

little snapshot” of herself, dressed in pants, galoshes, a beanie cap, and a sweater topped with a short jacket and an ascot wrap. She was

underweight again, but

she liked the photograph. It reminded her of how she had looked the first time she saw the first lady at

Camp Tera, twenty-one years earlier. “

It’s my most natural self, I think,” she wrote to ER, who pronounced it “

delightful.”

· · ·

AFTER THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION

ordered the

Housing and Home Finance Agency to reinstate

Morrow, agency officials abolished her position and offered her a secretarial job at less than half her previous salary. Neither

Murray nor Morrow had the “

heart” to ask ER to “to do anything else,” although Murray continued to keep ER informed.

The week before Christmas, Murray sent ER a chapter of her memoir as a gift. This particular chapter explored a painful issue—a longing to be white—that manifested itself in color prejudice among blacks. Several of Murray’s relatives were

passing, distancing themselves from their darker-skinned kin in order to escape discrimination, shame, and the stigma of inferiority associated with being black.

Aunt Pauline’s marriage to

Charles Morton Dame, a “

blond, blue-eyed” Howard law school graduate, had dissolved when he decided to pass for white and she refused to do the same. Under no circumstances—not even for love—would she renounce her heritage as an African American and a

Fitzgerald. “

This is an inside story which you can appreciate, having seen pictures of my

family,” Murray said in her cover letter to ER.