The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice (43 page)

Authors: Patricia Bell-Scott

Tags: #Political, #Lgbt, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #20th Century

The following morning, Elizabeth Eckford said a prayer with her family and took the bus. The day promised to be a scorcher; the sun was blinding. Wearing sunglasses and a black and white dress she and her mother had made for the occasion, Eckford walked the block from the bus stop to Central alone, her notebook tucked against her chest. Four hundred white protesters and a phalanx of guardsmen waited at the schoolyard. Jeers erupted as she approached.

A woman spat on Elizabeth’s new dress.

The guardsmen, whom she turned to for protection, offered none and blocked her path with bayonets.

Eckford tried to enter the building three times before turning to walk back to the bus stop. The hostile horde followed her there, where she sat down on a bench—petrified. Tears streamed from behind her glasses as she waited for a bus. When the other students arrived, the crowd turned them away, too. News photos of the scene shocked the nation.

The snapshot of Eckford and the throng of demonstrators must have reminded Murray of the night a group of white men surrounded her at the entrance to the

Norfolk, Virginia, train station. She was only eight.

Aunt Pauline, whom the men assumed to be white, had gone to the ticket counter unnoticed and inadvertently left Murray in the whites-only waiting room. Murray, an olive-skinned child, was “

out of place,” and her presence provoked a swarm of menacing stares. Like Eckford, Murray was cornered and “

too frightened to scream.” Fortunately, Aunt Pauline returned before she came to harm. They quickly boarded the train and took their seats in the black section.

On September 24, the day after a thousand protesters converged on

Central High with makeshift weapons, forcing the Little Rock Nine away for a second time, President

Eisenhower sent one thousand paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock. He also federalized the Arkansas National Guard. The decision to deploy troops was difficult for Eisenhower. He had tried to negotiate with Faubus, and he had urged civil rights leaders, much to their irritation, to have “

patience and forbearance.” But after the governor refused to obey the court order and quell the violence, Little Rock mayor

Woodrow Mann asked for federal troops. The president had no recourse, he told the nation in an address telecast from the White House. As commander in chief, he was obligated to uphold the law and to take action against “

mob rule.”

· · ·

BY MAY

1958, when

Ernest Gideon Green graduated from Central, the first black student to do so, Murray could hardly keep her mind on her job. She found it disconcerting to be in her elegant Madison Avenue office, combing through law books, drafting background papers, while black students in the South risked their lives to get an education. She jumped at the chance to support the Little Rock Nine when a disagreement between them and the

NAACP arose.

The association had taken the unprecedented step of awarding the

Spingarn Medal to the students as a group (all previous medals had been given to an individual), and they were thrilled—until they learned that Daisy

Bates, their counselor and chief strategist, was not a corecipient. An incredulous

Melba Pattillo asked, “

How can they draw a line like that? Yes, it was rough on us but she went through things which seem humanly impossible.”

Carlotta Walls declared, “

Mrs. Bates and the nine of us are all one. Without her, we’re like a head without a body. She should have been included.” Ernest Green put it simply, “

Mrs. Bates is more deserving than the rest of us.”

Bates had not only coordinated every move the students made, she’d gone with them to Central and to meetings with authorities. They gathered at her home before and after school to fortify themselves. She and her husband,

L. C. Bates, faced death threats all year. They risked foreclosure on their home, as subscriptions and advertising revenue for the

Arkansas State Press

, the weekly newspaper they owned and published, plummeted. Their sacrifice and support meant so much to the students that they unanimously agreed to refuse the award unless the NAACP named Bates as well.

When Murray heard about the controversy, she insisted that the

NAACP make amends for snubbing the person who’d engineered the desegregation of Central High. She believed that Daisy Bates was as vital to the school integration movement in Little Rock as

Martin Luther King was to the bus boycott in

Montgomery. “

Just as a baseball fan cannot think of the last decade of the Dodgers without thinking of

Jackie Robinson or the New York Yankees without thinking of their manager,

Casey Stengel, it is impossible,” Murray wrote to the Spingarn Award Committee, “to think of the Little Rock Nine without thinking of their manager, Daisy Bates.” Not to acknowledge Bates as a corecipient was a slap in the face to the parents who had entrusted their children to her and to the local branch of the NAACP, for which she served as president. Murray must have also wondered, given her previous experience with male leaders in the NAACP, if the fact that Bates was a woman had influenced the committee’s actions.

Sentiment for honoring Bates ran strong.

The stories about the controversy that appeared in the black press left no doubt as to the sympathies of most editors. The campaign for Bates made an impact. For the first time since establishing the award, the committee changed its vote and unanimously agreed to name Daisy Bates as a corecipient.

· · ·

IN JUNE

1958, Daisy Bates and the Little Rock Nine took a four-day holiday to New York City, compliments of Local Six of the

Hotel and Club Employees Union. The reception they received from Governor

Harriman, Mayor Robert

Wagner, and local civic groups was a welcome contrast to the antipathy they confronted at home. Local Six honored them with its annual

Better Race Relations Award. Fourteen hundred people came to a luncheon for them that the

Utility Club hosted at the

Waldorf-Astoria. Area youth bands feted them with a parade. The group visited the United Nations, the Statue of Liberty, Coney Island, and Broadway, where

Lena Horne and

Ricardo Montalbán greeted them backstage before a production of the musical

Jamaica

.

On June 15, Bates and the students spoke at a rally sponsored by the NAACP at Brooklyn’s

Concord Baptist Church. Murray squeezed into the packed balcony, where she could “

see every movement and expression of the platform guests.”

Ted Poston, who had lived with the Bateses while covering the story for the

New York Post

, introduced the students. Their maturity and courage moved Murray. She found it remarkable that after a year of unrelenting abuse, they appeared to be typical teenagers.

Fourteen-year-old

Carlotta Walls, the youngest girl, credited

Rosa Parks as her inspiration.

Gloria Cecilia Ray, fifteen, had an aptitude for science. Elizabeth

Eckford remained resolute, notwithstanding her encounter in the schoolyard. Sixteen-year-old

Thelma Jean Mothershed had rarely missed a day of school, even though she had a heart condition. Fifteen-year-olds

Melba Pattillo and

Minnijean Brown were fans of the handsome young crooner

Johnny Mathis. Fourteen-year-old

Jefferson Allison Thomas, the youngest of the boys, loved to run track.

Terrence James Roberts, fifteen, professed an interest in social work and law. Ernest

Green, sixteen and the only senior, enjoyed playing jazz on his saxophone.

Murray was especially interested in Daisy Bates, whose petite stature belied her strength. No matter how many times white classmates had hit, cursed, shoved, kicked, tripped, spat on, or otherwise attacked her charges, Bates had counseled them not to retaliate. Her account of what the children had endured brought Murray and everyone else to tears.

The audience responded with a $1,100 donation to the NAACP for expenses related to the case.

Murray managed to have a private conversation with Bates, during which she described the campaign to run her and her husband out of town and to shut down the

Arkansas State Press

before school resumed in the fall. White supremacists had stuck a burning

cross in the Bateses’ yard, hurled bricks through the window of their beautiful ranch home, threatened advertisers, beat up carriers, and confiscated their newspapers. The couple had already lost $10,000 in advertising revenue.

Eager to help, Murray came up with “

a perfectly mad idea” of replacing the lost revenue by getting a thousand people to purchase four inches of ad space at ten dollars each. Those who bought space could have their names published or have the space left blank or use “

a catchy pseudonym.”

Murray sent a ten-dollar check for ad space, and then she wrote to ten people, asking them to do the same. “

The chips are really down in Little Rock,” Murray warned ER. “May I count on you?”

· · ·

THE SOVIET PRESS HAD PEPPERED

ER with questions about Little Rock during her tour. Now that she was home, she joined the fray and sent a check to the

Arkansas State Press

“

for an advertising space at the request of Miss Pauli Murray.” ER profiled Daisy Bates and the students in “My Day,” paraphrasing a section of one of Murray’s letter.

This group has made a very fine impression here. The dignity and gallantry of Mrs. Bates is easy to see, and the young people carried themselves with dignity, too. It is good to know that one of these children graduated from school, making the honor roll for several successive months, and another one won a prize for a biology exhibit.

In looking at the group, you wonder why anyone would have wanted to keep them out of an American school or to do them harm. It is to be hoped that their courage will make it easier for other children to follow in their footsteps.

ER condemned the people who harassed the students, and she praised those, black and white alike, who refused to back down. She was convinced that there were Arkansans ready and willing to integrate the schools. All they needed to step forward was strong leadership from the federal government. ER’s frustration with the president led her to goad him in her column. “

I think instead of sending troops,” she wrote, “I wish President

Eisenhower would go down to Little Rock and lead the colored children into the school.” No matter what segregationists believed or wanted, “

the world has changed,” she asserted. “

The old doctrine of equal but separate cannot hold any longer.”

· · ·

ON JUNE 21, 1958,

barely a week after the Little Rock Nine’s trumpeted visit to New York City, Federal District Judge

Harry J. Lemley granted the Little Rock School Board’s request to postpone integration for two and a half years. Lemley acknowledged that the black students had a constitutional right to attend Central, but he said the pandemonium besetting the city proved that the time was not right.

Two days following Lemley’s ruling, Lester

Granger,

Martin Luther King,

A. Philip Randolph, and

Roy Wilkins went to the White House and asked President Eisenhower to articulate and implement “

a clear national policy” supporting school integration. When Pauli Murray read that the president had given the men no indication that he would aggressively back the

Brown

decision, she put pen to paper again.

In a testy proposal to NAACP board chairman

Channing Tobias that she copied to ER, Murray urged the organization to mobilize “

economic resources to aid the victims of economic reprisals in the South” and to develop “cooperatives, credit unions and other organizations of economic advancement.” What was needed, she argued, “is a

‘United Negro Appeal’ similar to the fund-raising drives of the ‘

United Jewish Appeal.’ ”

Despite the efforts of supporters around the country, the

Arkansas State Press

folded the next year, the

Bateses left town, and state officials closed the Little Rock public schools to avoid integration. During the 1958–59 school year, approximately 3,500 black and white Little Rock high school students were shut out of the public schools. Most black students, having little means to travel to other cities for schooling, did little if any academic work. White students had the option of attending private alternative schools, which were segregated, as well as commuting to schools outside the district. The schools would reopen for the 1959–60 term, but the Bateses would not return to Arkansas until 1965. Daisy Bates resurrected the

Arkansas State Press

in 1984, and it would survive until 1997. Fifteen years after Murray proposed the concept of a

United Negro Appeal to the NAACP, a group of activists would establish the

National Black United Fund to create and sustain economic institutions within African American communities.

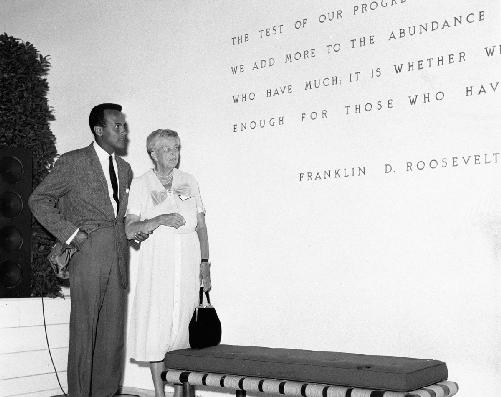

Entertainer and activist Harry Belafonte with Eleanor Roosevelt at the World’s Fair, Brussels, 1958. The housing problems he faced in New York City, like the eviction notice whites served Murray and her sister Mildred in Los Angeles fourteen years earlier, made racial discrimination a personal issue for ER.

(Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library)