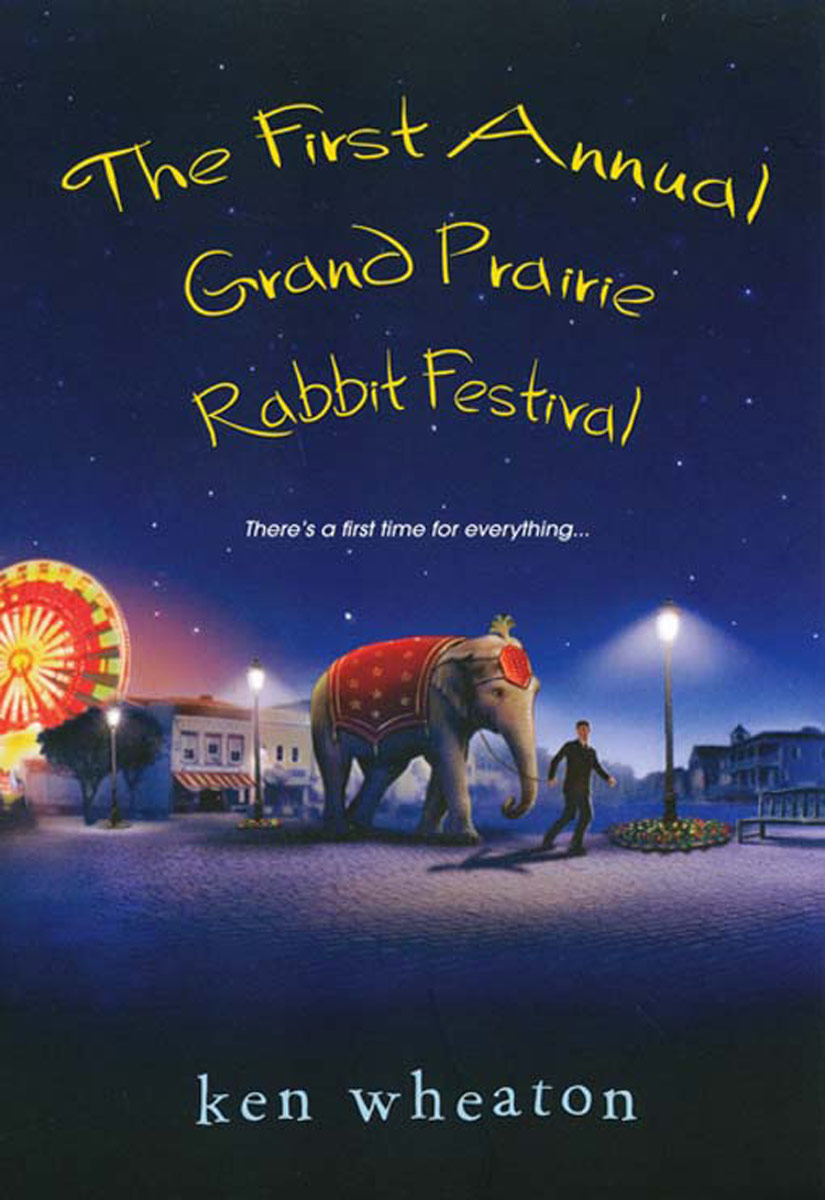

The First Annual Grand Prairie Rabbit Festival

Read The First Annual Grand Prairie Rabbit Festival Online

Authors: Ken Wheaton

The First Annual Grand Prairie Rabbit Festival

“You have to watch these Louisiana boys. They can drink you under the table, and some of them can write you under the table. Ken Wheaton can do both. He’s a wild one, and this is a sparkling debut.”

—Luis Alberto Urrea, author of

Into the Beautiful North

“Warmed my chest faster than a double shot of Wild Turkey and kept me laughing through the night. This is a rollicking, wonderfully irreverent debut. It’s also a charming love story with a heart as big as Louisiana. I am a huge Ken Wheaton fan.”

—Matthew Quick, author of

The Silver Linings Playbook

“A frustrated priest who smokes, drinks, and curses like a sailor, a loveable centenarian matriarch whose appetite for Crown Royal is matched only by her busy-body compulsion to counsel on any and all matters, a feisty flock of Cajun gals and gents who know how to get any ball rolling—all are unforgettable characters on a mission that’s not so holy and that gives new meaning to the notion of Southern Gothic. Add a carnival, the aroma of gumbo and fried turkey, and a little Zydeco dancing, and it’s easy to see why Ken Wheaton has produced a highly original yarn that is hilarious, beguiling, and, at times, warmly moving.”

—James Villas, author of

Dancing in the Low Country

and

The Glory of Southern Cooking

“Ken Wheaton’s fictitious story of a real small community in Grand Prairie, Louisiana, will keep you entertained and laughing out loud! Wheaton thoroughly describes the tradition and passion for the Cajun French way of life. Strap on your waders and get ready to trudge through some of the most colorful characters in the South.”

—Helen Pursell, Fifth Annual Festival Du Lapin Queen

KEN WHEATON

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

For Susan…

and Mawmaw

This novel would never have existed if not for a drunken bet proffered by Jason Primm on New Year’s Eve in 2001. Also providing proper motivation for that long-ago first draft were Lynn Jones and Erin Gallagher. Thanks to all three for giving me the push necessary to move on to a new, more readable project.

Thanks to Jacquelin Cangro, not only for publishing me in “The Subway Chronicles,” but for providing excellent editorial feedback to take this work from a shoddy second draft to something someone might read.

Thanks to Jeff Moores, formerly of Dunow, Carlson & Lerner, for rescuing me from the slush piles, and to Peter Senftleben and the gang at Kensington Books.

Of course, I’d be remiss to skip Mama, Daddy, Gardiner, Amber, Brian, Seth, Jennifer, and Daniel, who’ve made me what I am and remind me where I’m from, and my son, Nicholas Jones, who gives me something to look forward to.

And, finally, thanks to my wife, Susan, who also provided invaluable editorial feedback and who, more importantly, puts up with me, motivates me, and believes writing silly books about silly subjects isn’t a silly pursuit.

A note about “yall”: While most consider y’all a contraction of you all, in all my years growing up in Louisiana, I never once heard the phrase “you all” uttered. Regardless of what the fancy-pants dictionary might say, yall is one word, a second-person personal pronoun used to address two or more people (never one person, despite what crappy TV writers and third-rate comedians would have you believe). Therefore, for the purposes of this book, yall is written as…well…yall.

Further, while there is a St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church in a town called Grand Prairie, Louisiana, and, there once was something called a Rabbit Festival, this book in no way reflects reality—or any research—on my part. In other words, the whole thing’s a damn lie.

The counter clerk at T-Ron’s Grab ‘n’ Go doesn’t bat an eye when I ask for two packs of Camel Lights, a bag of pork cracklin’s, and a pint of Crown Royal. Is it every day she’s confronted with a priest—black pants, black shirt, white collar and all—buying whiskey and cracklin’s before lunch?

The cigarettes are mine, the rest is for Miss Rita, who’s finishing out life in Easy Time Nursing Home, where the staff frowns upon booze and pigskin. Before I walk in, I place my purchases into my black leather satchel, alongside a Bible, a

Daily Missal

, and last week’s copy of

People

magazine.

“Hey, Father Steve,” the receptionist says when I enter Easy Time’s lobby, which is covered in the chintzy sort of Thanksgiving decorations you’d expect to see in a preschool or kindergarten. She’s a short, chunky girl with a curly helmet of dull brown hair and an overly pleasant smile. She strikes me as the type who, unable to find a suitable man and unwilling to settle for an unsuitable one, has come to a place where she’ll be appreciated and adored, where she can dole out a little of that love pent up in an otherwise lonely life. I wonder if she lives in a trailer full of cats.

“Hi, Marie. How you doing today, cher?” I don’t know why I put on the Cajun schtick for her, but I do.

“Aw, I’m doing good, and you?” she chirps. I swear her teeth just might explode right out of her head.

“Comme ci, comme ça,” I answer. “Can’t complain. How’s Miss Rita doing today?”

“Oh, she’s good today. She’s awake and sitting in her room.”

As opposed to what? Hopping around the grounds on her one leg? Playing roller hockey in the parking lot?

“Good, good. I’ll see you later, Marie.”

Miss Rita, as far as anyone can tell, is somewhere between 105 and 117 years old. No birth certificate. Her “birthday” rolls around in late November, early December and seems to fall on whatever day is convenient for Easy Time and the reporters who cover the occasion. Her grandchildren don’t mind. Miss Rita doesn’t, either, as long as someone makes a fuss over it.

Aside from one dutiful grandson, I’m Miss Rita’s only regular visitor. She’s not a member of my parish—St. Pete’s doesn’t have a single black parishioner—but she’s practically a member of my family. Miss Rita was “the help” Pawpaw hired for Mawmaw back in the days when it was still acceptable to call people “the help.”

I remember Miss Rita and Mawmaw sitting in Mawmaw’s kitchen, in a pair of old wooden rocking chairs, Miss Rita shiny black to the point of being purple, Mawmaw white and liver-spotted. They rocked in a counterrhythm, black forward, white back, white forward, black back, all day long watching soap operas. Soul poppers, Miss Rita called them. I guess there was plenty Miss Rita helped Mawmaw with—folding laundry, shelling peas, collecting eggs from the chickens, peeling shrimp. But I remember them most clearly in those chairs, rocking away and arguing about the existence of evil twins.

Mawmaw died when I was twelve and Miss Rita went right on living. Now Miss Rita spends her days in a nursing home, sitting one-legged in a wheelchair, watching TV alone. The newspaper reporters invariably describe her as slightly incoherent but happy, like a retarded child who doesn’t know she’s been handed a tough lot in life.

Daddy used to visit her a lot, which is where I picked up the habit, but not so much since he remarried fourteen years ago. I asked him about it once, but he didn’t want to talk about it.

I walk into Miss Rita’s room. She’s facing the window, her head thrown back on her shoulders, eyes closed, mouth opened, a little string of drool hanging down onto the T-shirt she’s wearing—a wet splotch sits right in the middle of Malcolm X’s forehead. Not quite what he had in mind when he uttered the words printed on the shirt: “By any means necessary.” The left leg of her jeans is rolled up and pinned to where the knee should be. It’s what she’s worn since the amputation ten years ago. The orderlies would prefer her to wear a robe or a housedress, but I’m sure they found it easier to let her have her way. Her skin’s faded in her old age to the color of dirt, and sitting there like that, she looks like a piece of discarded furniture.

A rap song blurts from the radio; every other word is bleeped out for airplay and I can still make out the phrase “Bitch, I’ma kill you.” One of the orderlies must have been listening to it. I twist the radio’s volume knob and Miss Rita moves.

“Boy, you better put my program back on.” Her voice is a whisper of its former self, but it still demands respect. She told me once when I was a child, “Never, ever fear no man. You fear God, but no man. God. And Miss Rita, too. Boy, you better watch out for me, too.”

“You sure you don’t want some Cajun or zydeco music, Miss Rita?”

“Yeah, I’m sure I don’t want no Cajun or zydeco music. Your mawmaw made me listen to that for thirty years. Tired of that noise. Now put that radio back on 95.5 before—” she says, but falls silent as the door swings open and Marie pokes her head in. “Yall doing okay?”

“Just fine,” I say. Miss Rita’s head falls to her chest. She’s all smile and drool and babbling while she picks at some imaginary spot on her T-shirt. “Just having ourselves a little visit.”

When the door closes, Miss Rita’s head snaps back up. “You bring my stuff?”

“Yeah, I brought it. You sure you should be drinking this?”

“You sure you should be putting your pecker in them little boys’ behinds?” she shoots back at me, and starts cackling.

“Now, c’mon, Miss Rita,” I say, blushing for no good reason.

“Now, c’mon nothing. You quit bugging me about my little medicine, then. Same thing every time. I’m the one a hundred years old. Think I know what I should and shouldn’t do. Lotta good not drinking did your mawmaw.”

“But what about the cracklin’s? All that salt and fat. You don’t even have teeth to chew them with.”

“I got gums. All I need. Now give.” I hand her the bottle in its little purple sack and the brown bag already going transparent from the grease. “All them years of dumping them bowls of okry gumbo your mawmaw tried to force you to eat and this is the thanks I get? You getting on my case all the time?”

She has me there. She was my only ally in the battle against Mawmaw and her okra gumbo. Any other gumbo I loved—chicken and sausage, gizzard and hearts, seafood, squirrel. But okra? No way. I could write sermons about the pure evil that is okra. Fry it, sauté it, cover it in sugar and chocolate, or wrap it in bacon, but no way is anyone going to convince me that okra, especially in its slimy gumbo manifestation, isn’t concrete proof that Satan walks the earth.

Miss Rita’s hands stop trembling after she takes possession of her gifts. I half expect her eyes to bug out and for her to start hissing and talking about her “precious.”

Strong from years of work—picking cotton, shelling peas, snapping beans, smacking kids—her fingers make quick work of the plastic seal and cap on the bottle. I remember those fingers taking hold of my ear and dragging me off for a switching.

She takes a slow pull, says, “Ahhhh,” and smacks her lips before placing the purple Crown Royal bag into a cookie tin with a nest of others like it. I wonder who her connection was while I was away at seminary, but I don’t bother asking. “None of your damn business,” is the reply I’d get.

She takes another pull from the bottle and pops a cracklin’ into her mouth, rolls it around, and sucks on it noisily.

“Mmmmmmm-mmm. Never get tired of that,” she says, slapping her knee.

Our little ritual over, she turns her full attention to me.

“Now, what’s your problem, boy?” She nods at a calendar on the wall. A twenty-something black man in a fireman’s hat and a Speedo lies stretched out on a rock. “You a week early for your regular visit.”

“I can’t come at other times?” I counter.

“You can come any time you want, as long as you remember to bring me something. Now, what’s your problem?”

“I don’t know,” I say. And I don’t. Well, I do. Kind of. Three months into my first solo assignment, just twenty minutes up the road in Grand Prairie, Louisiana, I’ve grown bored. Absolutely and utterly bored. But I didn’t come here to whine about malaise to a woman whose mother was born a slave.

No. The problem is boredom leads to other problems of the heart and soul and mind—or, in my case, the optical system. I’ve been seeing things. Well, one thing in particular: a red blur flitting around the church, always near the edge of the grounds, in the trees or by the road. I’m pretty sure it’s not a ghost. If it is, it’s a peculiar one that avoids the cemetery and the inside of the church. At first, I told myself it was simply a trick of the eye—a butterfly flitting by, a red leaf on the wind. Lately, I’ve grown partial to the theory that it’s a symptom of a massive brain tumor. I can all too easily imagine how Miss Rita’s going to respond.

But there’s no need—or time—to explain. She’s quick with her own conclusion: “What you need is a woman.” She points a bony finger at me.

A woman? Mama doesn’t even bring that one up anymore. Besides, that’s the last thing on my mind. A woman? That part of my mind has been cauterized.

“Can’t have a woman,” I say.

“Don’t matter. You still need one.”

“Well, it does matter. I’m a priest. Can’t have one.”

“Them Baptist preachers over at Zion got women. Hell, that main one there got him three or four from what I hear.”

“Them Baptist preachers don’t let their people drink.”

She pauses for a moment, takes another sip, and fixes her eyes on me. “I bet you a woman do you a lot more better than a beer anyway.”

“Hmmph,” is all I can think to say.

“You not one of them likes men or little boys?”

“No, Miss Rita,” I snap.

“Hey, now. Just checking. You never know these days. You never know. But Lord, it’d kill your mawmaw if she wasn’t dead already.”

“Well, she’d be fine because I’m not.”

“There’s your problem, then. Need a woman. Ain’t natural for a man to be without a woman. Bible says so.”

“The Church says—” I start.

“The Church nothing. I had the Bible read to me about five thousand times in my life. Ain’t a damn thing in there about priests not getting married.”

When did she become a theologian? Of course, she’s right. Nothing in the Bible about it at all.

“Look. I can’t. Okay? It’s the rules. That simple.”

“Hmmph. Rules say you can’t have altar girls, either.”

She glares at me. I glare back. I never told her about the altar girls. Which means I’ve become a rumor already. The new priest in Grand Prairie adding another chapter of crazy to that little town’s history. She pops another cracklin’ in her mouth and takes another swig of whiskey. She wipes her mouth with the back of her hand, bobs her head in rhythm with the hip-hop coming out of the radio.

“There’s nothing in the rules against altar girls,” I say. “Besides, I couldn’t find any boys.”

“Wonder why,” she says. “Some strange man living alone in the woods without a wife. I wouldn’t let my sons go around him, either. People read them stories, you know.”

“But they trust me with their daughters?” I say, knowing full well what the response is.

“Probably didn’t even cross their mind you’d be interested,” she says, laughing again.

At this point, she’s already enjoying herself at my expense far too much, so I decide to save my ghost story for another time. “I’m sure there are other good explanations,” I say, not entirely convinced myself.

“There always is an explanation, isn’t there? Well, I got a simple one for you. You need a woman.”

The last thing I want lousing up my life is a woman. I don’t want one and don’t need one. Miss Rita is wrong about that. Wrong as a Scientologist. Forget the rules of the Church. I like my life simple, and simplicity is the last thing I associate with women.

Yet now, at this very minute, I have two women-in-training traipsing about my altar, their fruit-scented shampoos making it next to impossible to stay in that space I inhabit when I’m saying Mass—the zone, if you will.

I’d waited a month, an entire month, before asking for altar boys. To be honest, I don’t really need them. But the altar felt naked without them. Besides, the priests in all the other parishes have them. So I put a notice in the church bulletin and made a few announcements during Mass.

The following Monday, a young girl with strawberry blond hair knocked on my door.

“Yes, my child?” I asked in my most priestly voice, immediately feeling like an ass. Thirty-two years old and there I was saying, “Yes, my child?”

“Mama sent me to help you. Daddy said it was okay.”

“Help me? With what?”

“I don’t know,” she said, shrugging. Her thick accent made it sound like a one-word question, Ahduhno? “With the altar and stuff, I guess.”

“Really?” was the only thing I could think to say. I had her write her name and number down and told her I’d call. Denise Fontenot. She dotted the

i

in Denise with a heart.

Five more girls followed, all about thirteen. Two for each Mass. Not one single boy.

And now, instead of focusing on the Blessed Sacrament of the Eucharist, I’m overly aware of my surroundings.

This is not a good thing in St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church in Grand Prairie, Louisiana. Doubly so at the Saturday evening Mass, when the old-timers stroll in out of the woods.

For example, in any other congregation, the old man burping in the fifth pew, on my right hand side, would send a ripple of arched eyebrows, turned heads, and covered giggles through the church. But not here. Mr. Boudreaux can sit there and let one rip, his big owl eyes blinking away like all’s just peachy keen.

Then a fart echoes from one of the pews to my left.

No one seems fazed by this. The only two people in St. Peter’s who seem to notice at all are the Smith boys, who attend twice a month when they’re visiting their father out here in the sticks. I feel for those two boys, spending a Saturday night in the Grand Prairie wilderness while their friends are getting pizza delivered to their front doors in Opelousas.

Opelousas, twenty minutes down the road via the Ville Platte Highway, is where I grew up. With a population of fifteen thousand people, we were a veritable metropolis. And we had a name for places like Grand Prairie: Bumfuck, Egypt. Bumfuck. A good word to be thinking while saying Mass. Good work. The Lord, no doubt, is smiling upon me.