The Flames of Shadam Khoreh (The Lays of Anuskaya) (43 page)

Read The Flames of Shadam Khoreh (The Lays of Anuskaya) Online

Authors: Bradley Beaulieu

“

Yeh

,” Nasim said, his gaze suddenly distant. “Sariya and Kaleh both.”

“Did you see where she went?” Soroush asked.

Nasim shook his head.

“She may be dead,” Nikandr said, “fallen from the mountain.”

His words were more hopeful than he knew them to be.

“She’s gone,” Soroush said. “Gone with the Atalayina.”

They were silent for a time. Then Nasim coughed and said, “We’ll find it.”

Soroush laughed at this, long and hard, like an old man amused by the callow thoughts of a child.

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

Nikandr helped Nasim to limp out from the tunnel and into a world completely different than the one that had been there before the storm. Trees were felled. Branches and boughs lay everywhere. The entire landscape was covered in a fine red dust. It made this place look completely alien, as if Nikandr had walked up the mountain and crossed a doorway to another world. The aether had been explained to him many times—by his mother, by his sister, by Atiana—but he’d never truly appreciated what had been meant by a world filled with but a handful of colors until he’d seen this.

Soroush ranged ahead, looking for Ashan and Sukharam, calling for them from time to time. Nikandr helped Nasim slowly down the steps. It felt good to be with Nasim again, to help him in some small way. Nasim was like a nephew to him now, family by deed if not by blood. As they neared the first switchback, a bird with russet wings and a bright yellow breast fluttered down and landed on the exposed roots of a fallen tree. It seemed to be watching Nikandr and Nasim approach, and it remained even when they came within a few paces of it.

Both of them stopped and stared, too intrigued to move past. The bird chirruped a song, a delicate thing that made Nikandr think of tall trees and hidden songbirds.

“It’s beautiful,” Nikandr said.

“It’s a golden thrush.” Nasim stretched his hand toward the bird with his forefinger crooked. “They used to come to Mirashadal on their migrations among the eastern islands.”

The bird studied Nasim’s finger. It twitched its head this way and that, shook its wings and then lay still.

“There aren’t many on the motherland, but those who find them are said to have good fortune.”

“Good,” Nikandr replied. “We need a bit of that right now.”

Nasim waited patiently, unmoving. Nikandr actually believed the thrush was about to leap onto his outstretched finger—it would stare at Nasim’s finger, then flap, then stare again—but then it launched into the air and flapped southward and soon was lost among the sparse trees that still clung to the mountainside.

At last they came to the place Nikandr judged that he’d left Ashan and Sukharam to continue on up the mountain. It felt like days since he’d done so, and he wasn’t entirely sure this was the same place at all, for the landscape looked completely different. Soroush was searching to the right of the path, so Nikandr left Nasim on the trail and searched along the left-hand side. He found one of their ab-sair a while later. It was dead, crushed by a fallen spruce. He continued and found another ab-sair standing among the devastation, unharmed except for some gashes across its withers and its broad, muscled chest. He found two more of their mounts a short while later, and then, when he was just ready to call for them again, he saw Sukharam, waving atop a pile of broken boughs and branches and other detritus.

“Where’s Ashan?” Nikandr asked when he’d come close.

“He’s below. Come.” And with that Sukharam climbed down into the trees that—now that Nikandr was closer—looked like they’d been carefully placed to form a shelter.

Nikandr climbed up and then down through the hole where Sukharam had disappeared. There he found Ashan leaning over what Nikandr could only describe as the most ancient man he’d ever seen. His eyes were sunken, but they seemed alert. Tears leaked from them. If he was concerned by Nikandr’s presence, he didn’t show it. He merely moaned and repeated one word over and over.

“What’s he saying?” Nikandr said, unable to make it out.

“

Abar

,” Sukharam replied. “It means

gone

in Kalhani.”

“Gone,” Nikandr repeated, trying the word for himself. “What’s gone?”

Ashan looked up. His eyes were wide, searching beyond the broken land around him. He was more shaken than Nikandr had ever seen him. “The walls,” he said. “With the Tashavir dead—all of them except for Tohrab—the walls around Shadam Khoreh have finally fallen. All that remain now are the wards on Ghayavand. And when those fail, which they surely will, our final days will have come.”

Nikandr didn’t know what to say to that. He was right, of course, but he couldn’t think clearly in the confines of this place.

“Come,” Nikandr said, “there’s someone you should meet.”

Carefully, they hoisted Tohrab out of the shelter and moved down to level ground. By this time Soroush and Nasim were standing there waiting for them. Sukharam merely stared awkwardly, as if he couldn’t quite believe that Nasim was alive. But Ashan’s face changed. The horror of moments ago faded and was replaced with a smile like the break of dawn.

He strode forward and took Nasim into a deep embrace, swaying him back and forth as he began to laugh. As the laughter continued, Nasim looked shocked, and perhaps confused at such an emotional display. Who knew the last time Nasim had felt such a thing? Probably not since the two of them were together last. When Ashan’s laughter finally faded, he pulled Nasim away and stared into his eyes. “It’s good to see you,” Ashan said at last.

“You as well,” Nasim said softly.

Soroush cleared his throat and motioned to the ab-sair. “We should go.”

It brought a measurement of sobriety to the group, and soon they were mounted up and riding back toward the Valley of Kohor.

Nikandr rode near the head of the group. Nasim sat behind him on the saddle, holding Nikandr’s waist as the ab-sair plodded onward. It had been a day since the devastation at Shadam Khoreh, and still the ab-sair huffed noisily, clearing their nostrils of the red dust. Ashan and Tohrab came next on another ab-sair, and at the rear were Soroush and Sukharam.

They rode in silence down a path that would deliver them to Kohor by a more easterly route than the one they’d taken here. They didn’t wish to risk coming across the Kohori unprepared, but they needed to go back for Atiana and Ushai.

They came to a curve in the trough they were following, a dry wash that looked like it hadn’t seen water in months. When they took the curve, a landscape of scrub brush and brittle grasses met them. The land was peppered with boulders, especially along the left slope, where a wide swath of rock and stone had crumbled and fallen across their path. It was not insurmountable, but it would take time to cross, and they’d need to tread carefully, for the stones were uneven and sharp. Far ahead, beyond the slide, Nikandr saw the shoulders of the mountains fall away, revealing blue skies beyond. That was where Kohor lay, where Atiana was held prisoner. He only hoped when the Kohori learned of what had happened that they would listen to reason, that they would hear the truth in their words and not hinder them on their quest to close the rifts on Ghayavand. His stomach gave a twinge every time he thought about Atiana, the pain she’d surely endured.

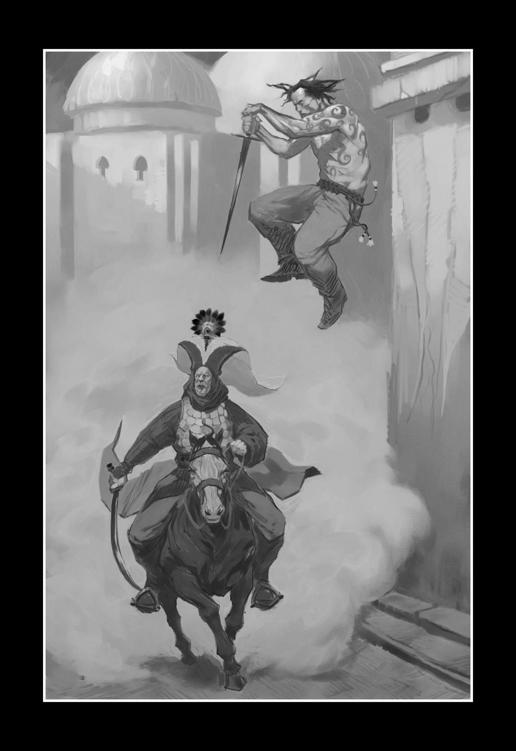

They were approaching the rock slide, and Nikandr was just about to dismount when he saw movement from his left. No sooner had he turned his head than a figure rose from behind the fallen stones. Then another rose, and another. A dozen, each of them bearing a musket, which they trained on the six of them carefully. Nikandr’s heart pounded in his chest. These were the janissaries, the very ones the Kohori had chased off of their eastern border. He thought they might have given up, or returned to Andakhara to resupply, or perhaps rally more men.

But they hadn’t. They’d remained and bided their time.

And a moment later, Nikandr understood why. Beyond the men, standing and watching, was a tall woman. She wore the roughspun dress of the wodjana. She had known that they would come to this place, and she had led the Kamarisi’s men here. By the ancients, he

recognized

this woman. She was the very one who’d come to Khalakovo and beseeched Ranos to treat with the Haelish Kings. She was the reason Ranos had asked Atiana’s sister, Ishkyna, to fly west and speak with them. She was the reason Styophan had been sent afterward with gemstones and muskets and cannons, so that the Haelish could continue their long struggle with the Empire. How in the name of the eldest men could she have found her way here? And what might it mean for Styophan, for their cause in the west?

The wind began to pick up a moment later. Dust swirled at the base of the stones. It grew no more than this, for the leader of the janissaries, a man with a golden broach pinned to his white turban, fired his musket.

The ab-sair behind Nikandr released a long moan and collapsed to the ground. Ashan and Tohrab fell. Ashan managed to roll away, but Tohrab was still too weak, and he fell heavily to the ground.

“Do not summon hezhan,” the commander of the janissaries said in Yrstanlan. “Do not summon hezhan,” he said again in Mahndi as he pulled a flintlock pistol from his belt and climbed the mound of rocks. As he stepped carefully down the other side, he pointed the pistol at Nikandr. “Come down from those mounts.”

Nikandr looked beyond him, to the blue skies of Kohor.

“Come down!” the commander shouted.

Nikandr complied. Nasim followed, as did Soroush and Sukharam.

In short order, all six of them had been locked in cuffs of heavy iron—around their wrists, ankles, and necks. The ones around their wrists were chained, but the ones around their ankles were left free so that they could ride. But the iron would serve to bind the arqesh. Ashan and Sukharam and Nasim and Tohrab—they were all of them gifted, but even they would not be able to touch Adhiya with so much iron around them. Nikandr harbored some hope that Tohrab, born of a different age, might be able to rise above these restraints, but one look at him told Nikandr otherwise. Tohrab was sunken, hunched over in his saddle as if he could barely remain upright, much less draw from the world beyond.

Where they would be taken now, Nikandr didn’t know. To Andakhara. To Tethan Hohm. To Alekeşir. And there they would await a Kaymakam, or Bahett, or perhaps even the Kamarisi himself.

They were riding for nearly an hour when the commander looked sharply to his right, then behind him along the line of plodding ab-sair. He reined his mount to the side, looking severely at the landscape behind them.

He drew two of his men away and spoke to them in low, harsh terms. The two men scanned the landscape, as their commander had, and then they rode back the way they’d come.

It took Nikandr a few moments to realize what they were so excited about.

Somehow, improbably, the wodjan was missing. He remembered seeing her as the shackles were being secured, but he couldn’t remember her taking a saddle, couldn’t remember seeing her on any of the broad-chested beasts as they’d started riding north.

The two janissaries returned at nightfall. They reported to their commander, and he listened, his body going rigid at their news. Clearly they hadn’t found her.

As the men began dismounting and setting up camp, the commander locked eyes with Nikandr.

Nikandr didn’t know why he did it, but he found it vastly amusing that the woman from Hael had escaped. He laughed, good and long, for the first time in what felt like months.

He wondered if the commander would pull him down from the saddle, perhaps beat him for his impudence. But he did not. He merely set his jaw and pointed his gaze to the fore, as if he knew he deserved it.

PART II

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

Atiana lay against the floor of a pitch-dark cell. She took measured breaths, drawing in the mineral scent of the air, exhaling it as slowly as she drew it in. She was naked, her skin in direct contact with the cold stone. She tried to convince herself she was surrounded by freezing water, that a servant awaited her return from the aether, that above her lay the bulk of Galostina. But however she tried to fool herself, she knew it was not the same. It felt different. It smelled different. And by the ancients, it was too warm.

More than this, though, she

desperately

wanted to enter the aether—to find Nikandr and the others, to find Ishkyna, to summon what help she could—and desperation was one of the surest things that would keep a Matra from entering the midnight world.

Part of her wished for a censer, wished for a knife and coals so that she could burn her blood and cross over without the embrace of the frigid waters of the drowning basin. Another part was horrified at the thought. And another part still wanted to enter the aether as she had on the small island Duzol and in the city of Vihrosh on Galahesh. She’d done these things. Why couldn’t she do it again? Why did she need water

or

blood?

She shivered.

The blood. Her own blood. How burning blood could allow her to cross over she had no idea. She wanted to believe that some combination of time and place and her own mindset had allowed her to cross over, and yet there was no denying what had happened.