The Fry Chronicles (14 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

She seemed, like Athene, to have arrived in the world fully armed. Her voice, her movement, her clarity, ease, poise, wit … well, you had to be there. One of the best things any performer on stage can do, whether stand-up comic, torch singer, ballet dancer, character actor or tragedian, is to relax an audience. To let them know that everything is going to be all right and that they can lean back in their seats happy in the knowledge that the evening won’t be a disaster. Of course, another of the best things a performer can do is provoke a feeling of excitement, danger, unpredictability and instability. To let the audience know that the evening might fail at any moment and that they need to lean forward in their seats and watch intently. If you can manage both at once then you are really something. This girl was really something. Medium height with a perfect English complexion, she was gravely beautiful, extraordinarily funny and commandingly assured beyond her years. Her name, the programme told me, was Emma Thompson. In the interval I heard someone say that she was the daughter of Eric Thompson, the voice of

The Magic Roundabout

.

Emma.

Fast forward to March 1992. For her performance as Margaret Schlegel in

Howards End

Emma has won the Academy Award for Best Actress. Journalists are ringing round all her old friends to find out what they think of this. Now, it is a kind of unwritten rule that when the press

ask you to speak about someone else you never say a word unless that person has cleared it with you beforehand. If one wants to talk about oneself to a journalist that is fine, but it really isn’t on to blather about a third party without their permission. One persistent journalist, having been more or less rebuffed by all of Emma’s old friends, somehow gets hold of Kim Harris’s number.

‘Hello?’

‘Hi, I’m from the

Post

. I understand you’re an old university friend of Emma Thompson’s?’

‘Ye-e-es …’

‘I wonder if you’ve anything to say about her Oscar? Are you surprised? Do you think she deserves it?’

‘I have to come right out and tell you,’ says Kim, ‘that I feel betrayed, let down and most disappointed by Emma Thompson.’

The journalist almost drops his phone. Kim can hear the sound of a pencil being sucked and then, he later swears, of drool hitting the carpet.

‘Betrayed? Really? Yes? Go on.’

‘Anyone who ever saw Emma Thompson at university,’ says Kim, ‘would have laid substantial money on her getting an Oscar before she was thirty. She is now just over thirty. It’s a crushing disappointment.’

Not as crushing a disappointment as that felt by the journalist who for one second thought he had a story. Kim, as he so often does, put it perfectly. That really was all there was to say. Plenty of other students were talented, some prodigiously so, and one might guess that with a fair following wind, the right opportunities and a measure of guidance and growth, they would have decent, or even brilliant, careers. With Emma you just saw her once and you knew. Stardom. Oscar. Damehood. That last is up to her of course but you can guarantee it will be offered.

Men like their actresses, if they are superb, to be air-headed, ditzy and charmingly foolish. Emma is certainly capable of … refreshingly different approaches to logical thought … but air-headed, ditzy or foolish she is not: she is one of the most clear-minded and intelligent people I have met. The fact that her second Oscar, two years after the first, was awarded for a screenplay, tells you all you need to know about her ability to concentrate, think and work. If it is tempting to be cross with people for having so many gifts lavished on them at birth, she has an abundance of kindness, openness and sweetness of nature that makes envy or resentment difficult. I am aware that we have entered the treacly territory of ‘darling she’s lovely and gorgeous’ here, but that is the risk a book like this was always going to run. I did warn you. For those of you who would rather take away some other view of the woman, I can tell you definitively that she is a talentless mad bitch sow who wanders the streets of north London in nothing but a pair of ill-matched wellington boots. She only gets parts in films because she sleeps with the producers’ animals. Plus she smells. She never wrote a screenplay in her life. She chains up a writer she drugged at a party twenty years ago, and he is responsible for everything published under her name. Her so-called liberal humanitarian principles are as false as her breasts: she is a member of the Gestapo and regrets the passing of Apartheid. That’s Emma Thompson for you: the darling of fools and the fool of darlings.

Despite or because of this we got to know each other. She was at the all-women’s college Newnham, where, like

me, she read English. She was funny. Very funny. Also extreme with her fashion sense. The day came when she decided to shave her head: I blame the influence of Annie Lennox. Emma and I were both in the same seminar group at the English faculty and one morning, after a stimulating discussion of

A Winter’s Tale

, we walked together down Sidgwick Avenue towards the centre of town. She pulled off her woolly hat so that I could feel the texture of her bare pate. In those days it was unlikely that anyone would have seen a woman as bald as an egg. A boy riding past on a bicycle turned to stare and, his panic-stricken eyes never leaving Emma’s shining scalp, rode straight into a tree. I never thought such things took place outside silent movies, but it happened and it made me happy.

Emma Thompson’s hair is starting to grow back.

The first term came and went without my daring once to attend an audition. I had seen that there could be actors, or one at least, as astonishing as Emma, but there had been plenty getting parts that I felt I could have played better, or at least no worse. Nonetheless I held back.

For the most part my life in college and in the wider university followed a blandly traditional course. I joined the Cambridge Union, which is nothing to do with students’ unions, but a debating society with its own chamber, a kind of miniature House of Commons, all wood and leather and stained glass, complete with a gallery and doors marked ‘Aye’ and ‘No’ through which you file to vote after the ‘Speaker’ has put the motion to the ‘House’. All a little pompous really, but ancient and traditional. Many in Margaret Thatcher’s cabinet had been Cambridge Union hacks in the early sixties: Norman Fowler, Cecil Parkinson, John Selwyn Gummer, Ken Clarke, Norman Lamont, Geoffrey Howe … that

bunch. I was not politically inclined enough to want to speak or attempt to work my way into the inner circle of the Union, nor was I interested in asking questions from the floor of the house or contributing to debates in any other way. I watched a few – Bernard Levin, Lord Lever, Enoch Powell and a handful of others came to argue about the great issues of the day, whatever they were back then. War, terrorism, poverty, injustice, as I recall … problems that have now all been solved but which at the time seemed most pressing. There was also a ‘comedy’ debate once a term, usually with a fanciful motion like ‘This House Believes in Trousers’ or ‘This House Would Rather Be a Sparrow Than a Snail’. I went to one where the handlebar-mustachioed comedian Jimmy Edwards, drunk as a skunk, played the tuba, told excellent jokes and afterwards – so I was told – fondled the thighs of all the comely young men at the dinner. I have since been invited many times to debate at Cambridge, Oxford and other universities and shiningly comely and shudderingly handsome have been some of the young men who have hosted the evenings. I never quite got the hang of the getting drunk and fondling the thigh business though. Whether that makes me a gallant and proper gentleman, a cowardly wuss or an unadventurous prude I cannot quite make out. Thighs appear to be safe around me. Perhaps this will change as I enter the autumn of my life and I cease to care so much about how I am judged.

Kim had immediately joined the University Chess Club and was playing for them in matches against other universities. Nobody doubted he would get his Blue, or rather Half Blue. You are perhaps aware that in Oxford and Cambridge there are such things as sporting ‘Blues’. You can represent Cambridge, whose colour is light blue, on the hockey field, for example, for just about every game of the season and be far and away the best player on the pitch for all of them, but if you miss the Varsity game, the one match against the dark blues, Oxford, you will not be awarded your Blue. A Blue, for either side, means you played against The Enemy. The Boat Race and Varsity matches in rugby and cricket are the most celebrated encounters, but there are Blues contests between Oxford and Cambridge in every imaginable sport, game and competitive activity from judo to table-tennis, from bridge to boxing, from golf to wine-tasting. The minor pursuits result in participants being awarded a ‘Half Blue’, and that is what Kim duly won when he represented Cambridge against Oxford in the Varsity chess match, at the RAC in Pall Mall, sponsored by Lloyds Bank. He played in that match for every one of his three years, winning the prize for best game in 1981.

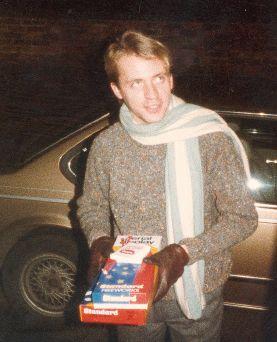

Kim in Half Blue scarf.

Kim and I were the closest of friends but we were not yet lovers. He pined for a second-year called Robin, and I pined for no one in particular. Love had mauled me too violently in my teenage years, perhaps. I had fallen in love at school so completely, intensely and soul-rippingly that I had made some sort of unconscious pact with myself, I think, that I would neither betray the purity of that rapturous perfection (I know, I know, but that is how I felt) nor would I ever again open myself up for such pain and torment (exquisite as they were). There were plenty of attractive young men in the colleges and about the town, and a more than statistically usual ratio gave the impression of being as gay as gay can gaily be. I remember one or two drunken evenings in my own or another’s bed,

with attendant fumbling, frotting, fondling and farcically floppy failure as well as more infrequent feats of fizzing fanfare and triumphant fleshly fulfilment, but love stayed away, and, sensualist as I am in many regards, I seemed to miss neither the rewards nor the punishments of carnality.

A week or so towards the end of the first term I was approached and asked if I would sit on the May Ball Committee. Most universities hold a summer party to celebrate the end of exams and the coming long vacation. Oxford has what they call Commem Balls, Cambridge has May Balls.

‘We get one fresher on the committee every year,’ the President of the committee said to me, ‘so that by the time the May Ball comes around in your last year, you’ll know what it’s all about.’

I never dared ask why they had selected me out of all the freshers to be the one to sit on the committee, but I took it as a great compliment. Perhaps they thought I exhibited style,

savoir faire

,

diablerie

, dash and a graceful party manner. Or perhaps they believed that I was the kind of biddable sucker who would be prepared to put in the hours.