The Fry Chronicles (18 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

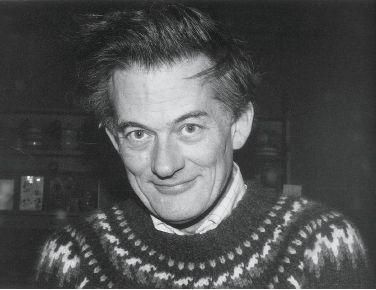

Authors: Stephen Fry

I had noticed from the programme that the staging was the work of Christopher Richardson, whom I had known when I was a schoolboy and he a master at Uppingham School.

†

I had a brief word with him afterwards, and he told me that the show had previewed at Uppingham.

‘The theatre has become quite a regular stop on the way between university and Edinburgh,’ he said. ‘You must bring some of your Cambridge people.’

‘Oh I don’t, I’m not … we wouldn’t …’

The drama I was doing at Cambridge suddenly seemed ordinary, worthy and desperately unexciting. I dismissed such unnecessarily negative thoughts from my mind. What was there to complain of?

The

accelerando

that had begun in the second term continued on my return. More drama, less academic study.

I now had the option of living out of college in digs or staying in and sharing with a fellow second-year. Kim and I chose to share, and we were rewarded with a stunning set of rooms in Walnut Tree Court. The ceiling had dark Elizabethan beams, and the walls were panelled in wood. Some of the panels were cut to reveal recessed cupboards and, in one place, an area of medieval painted plaster.

There were bookshelves, a good gyp-room, window-seats, leaded panes of warped glass of great antiquity and far from contemptible furniture. With our books, records, glassware and china, my bust of Shakespeare, Kim’s bust of Wagner, Jaques chess set and Bang and Olufsen record player we were as well set up as any students in the university.

The three terms of that second year have blended and blurred in my mind. I do know that it was then that I was asked to join the Cherubs, hurrah! The initiation ceremony required the draining down of heroically repulsive and impossibly combined flagons of spirit, wine and beer. One also had to recite the meaning of the Cherubs’ emerald, navy and salmon necktie: ‘Green for Queens’ College, blue for the empyrean and pink for the cherub’s botty.’ Another duty was to declare what one would do to advance the cause of the Cherubs and Cherubism. I cannot remember what I said, something arrogant about wearing the tie on television at every opportunity when I was a famous actor, I think. Another initiate, Michael Foale, announced that he would be the first Cherub to join all the other cherubs in heaven. When pushed for an explanation he said that he intended to be the first Cherub in space. It was a preposterous claim to make. Space travellers were either American astronauts or Soviet cosmonauts. At some later, slightly less incoherently drunken Cherubs party I discovered that he had been perfectly serious. He had dual UK/US nationality, his mother being American. He was already fluent in Russian, which he had taught himself, reasoning that the future of space exploration would depend on full cooperation and collaboration between the United States and the Soviet Union. He was into his third year of a doctorate in astrophysics and a member of the RAF’s Air Training Corps, able to fly just about anything that had wings or rotors. I had never encountered such focus and determination in anyone. Seven years later he was accepted by NASA as an astronaut. He flew his first Space Shuttle mission five years after that and retired having spent over a year of his life away from earth. Until 2008 he held the American record for time spent in space – 374 days, 11 hours and 19 minutes – which is still, needless to say, a British record. I would like to say that his resolve, dedication and commitment were a life-changing example to me. Instead I thought he was potty and blush to think how I humoured him.

The Cherubs. I know we look like wankers, but really we weren’t. Honestly.

Mike Foale invited me to attend the launch of his mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope in 1999, but I couldn’t go. He invited me again to his final launch in 2003, for which he was appointed Commander of the International Space Station. Again I had to plead other commitments. What was I thinking of? Surely I could have postponed whatever it was I was doing and travelled to the launch site to watch a remarkable man doing one of the most remarkable things any human can do? I regret missing the chance deeply. I hope today’s Cherubs at Queens’ have incorporated a toast into their rituals which recognizes the most illustrious and intrepid of their heavenly host ever to don the green, blue and pink.

I soon made sure that Kim was initiated into the Cherubs too, and perhaps as a kind of thank you, or more likely because he was such a generous soul anyway, Kim offered to have a dinner jacket made for me at a grand tailoring shop on the corner of Silver and Trumpington Streets. Ede and Ravenscroft, besides being fine fashioners of a gentleman’s dress suiting, were also makers of elaborate and distinguished academic, legal, ecclesiastic and ceremonial costume of all kinds from graduate gowns to royal robes. The double-breasted dinner jacket of heavy wool they made for me was a thing of rare beauty. The facings of the lapels were of black silk as were the stripes down the side of the trouser legs. Kim felt I should have a proper shirt with separate collar to go with it as well as a good silk black bow-tie. And how could any of this be worn without proper shoes? Kim was generous with his money, but he never used it to show off. Not once did he make me feel that I was a lucky recipient of his largesse, or put me in the position of being embarrassed or overwhelmed by it. The kindness was as much in the manner of his generosity as in the quantity of it, although the latter did keep our rooms in enviable luxury. Kim’s mother often sent large hampers from Harrods, cases of wine and quantities of cashmere socks for her beloved only child. His father worked in the advertising business, something to do with the sites on which posters were put up, and it was clearly a concern that flourished. My own family’s relatively modest prosperity did not, like Kim’s, run to truffles, pâté and vintage port, but my mother was able to exhibit more often than was comfortable for a sceptic like me a most uncanny ability to know exactly when and by how much my funds were depleted. A bill from Heffer’s, the Cambridge bookshop, might arrive in my pigeonhole and loom over me and deprive me of sleep that night, and the following morning there would be a letter from Mother with a cheque and little note saying that she hoped that this might come in useful. The sum seemed nearly always to cover the bill and leave a happy amount over for wine and cakes.

My sister Jo came to stay. She adored Kim and made friends with everyone, most of whom thought she was an undergraduate, although she was only fifteen. It was in a letter to her when she was back home that I wrote something that my father saw, something that made it clear that I was gay. He got a message through to the porter’s lodge at Queens’ asking me to ring. When I called he told me that he had seen my letter to Jo, that he was sorry to have done so, but that as far as the gay thing was concerned he couldn’t be happier …

‘Oh, and your mother would love to speak to you.’

‘

Darling!

’

‘Oh, Mama. Are you upset?’

‘Don’t be silly. I think I’ve

always

known …’

It was the most marvellous relief to come out in this way.

Papa.

Mama.

My scholarly duty of saying Latin grace in hall for a week came round. I began to write occasional articles and television reviews for a student newspaper called

Broadsheet

, and more and more parts in more and more plays came my way. I played a disc jockey in Poliakoff’s

City Sugar

, a poet in Bond’s

The Narrow Road to the Deep North

and a Classics don in a new play by undergraduate Harry Eyre. I played kings and dukes and old counsellors in Shakespeare and killers and husbands and businessmen and blackmailers in plays old, new, neglected and revived. If Kipling’s suggestion that to fill every minute with sixty seconds’ worth of distance run is truly, as he asserted, the mark of a man, then I seemed to have become one of the most virile students in Cambridge.

In the Christmas vacation that fell between the Michaelmas and Lent terms, I accompanied the European Theatre Group

on a tour of the continent, bestowing the blessing of

Macbeth

upon a bewildered population of Dutch, German, Swiss and French theatre-goers, mostly reluctant schoolchildren. The production was directed by Pip Broughton, who had been responsible for

Artaud at Rodez

, and she had cast Jonathan Tafler as the murderous thane. Illness prevented him at the last minute, however, which was a great blow to Pip, for she and Jonathan were an enchantingly devoted couple. I played King Duncan – a marvellous role for such a tour because he dies very soon in the play, and I could spend my time scoping out whichever town we were quartered in and be back in time for the curtain-call pregnant with information on the best bars and cheapest restaurants. The ETG had been founded by Derek Jacobi, Trevor Nunn and others in 1957, the year of my birth, and had earned a lamentable reputation for its frequent lapses from high seriousness and decorum. There was a rumour that the town of Grenoble had gone so far as to ban all Cambridge drama troupes from ever appearing in their town again after a notoriously drunken exhibition at a mayoral reception some time in the mid-seventies: well, drunken exhibition

ism

, if the story is to be believed. Our company was not as bad as that, but we did misbehave on stage. There is something about the sight of row upon row of serious Swiss schoolchildren with copies of Shakespeare on their laps studiously following the text line by line that brings out the devil in a British actor. A Word of the Day would be announced before curtain-up and prizes awarded to whichever actor could most often jemmy that word into their role. ‘There’s no weasel to find the mind’s construction in the weasel,’ I remember saying one night in Heidelberg. ‘He was a weasel in whom I placed an absolute weasel.’ And so on.

A fellow called Mark Knox, who played many parts, including the messenger who comes to tell Lady Macduff that the evil Macbeth is on his way and means her harm, discovered that his speech of warning could be sung to the tune of ‘Greensleeves’, which he did, a finger to his ear, to the great perplexity of a Bernese audience. The three witches’ ‘When shall we three meet again?’ was discovered to fit, with only minimal syllabic wrenching, the tune of ‘Hark the Herald Angels Sing’.

Somehow throughout all this, Barry Taylor, who had played the squeaking and gibbering Caliban in Ian Softley’s BATS May Week

Tempest

and had now been called in at the last minute to replace Jonathan Tafler, contrived to produce a superb Macbeth. If I was back early enough from my reconnoitring of the town I would stand in the wings and watch in admiration as, rising above, or sometimes even joining in, the practical jokes, he managed to convey murderous savagery, self-destructive guilt, boiling fury and terrible pain as well as I had seen. It is of course a truism of amateur acting that the cast always believes they are doing something that would stand comparison with the best professional theatre: it is rarely justified, but sometimes there are amateur performances which a pro would be proud of, and Barry Taylor’s Macbeth was one such. In my memory at least.