The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 (17 page)

Read The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 Online

Authors: Gary Ralston

William’s pleas of innocence fell on deaf ears and he was committed for trial with Emmott the following month. Bail was set at £50 for William and £100 for Emmott. Surely, justice was done on Friday 11 June when William was acquitted, but Emmott found guilty of dishonesty. The Western Daily Press noted in its edition of 12 June that the prosecution appeared willing to give Emmott the benefit of the doubt in his dubious publishing venture. It said: ‘A thousand copies [of Emmott’s Seaside Advertiser] were printed and the prosecution admitted that at the time Emmott may have been acting perfectly honestly. The paper, however, started under unfavourable auspices, only 500 copies being taken by Emmott. Last October he was supplied with another 100 copies and no further trace of the publication could be found. In the following March, however, advertisements were solicited and it was upon this the prosecution relied for a conviction…Mr Garland [William’s lawyer] urged that MacBeth acted bona fide and himself thoroughly believed in Emmott’s representations.’ The jury found Emmott guilty, and acquitted MacBeth. Emmott admitted a previous conviction at Liverpool (for felony, in October 1889). Sergeant Sharpe informed the learned judge that he had received a large number of complaints of this kind of conduct on Emmott’s part. Since 1896 the prisoner had collected money from over 1,000 people, receiving between £500 and £600. His Lordship said he was glad the police had taken pains to acquire information about Emmott and he passed sentence of 21 months’ imprisonment with hard labour.

The second marriage certificate of William McBeath, who married Sarah Ann Lambert on Boxing Day, 1898. There is no evidence to suggest he was a widower, as stated.

Following his escape from the clutches of the courts, William clearly felt he had little alternative but to seek a new start elsewhere in England, leaving behind whatever family he still had left in Bristol. By the end of 1898 he was in Bradford but, quite probably, ran the risk of falling foul of the law once again when he married for the second time, to a Sarah Ann Lambert, with whom he was sharing an address at No. 28 Marshall Street in the Horton district of the Yorkshire town. There is no doubt that the marriage solemnised at the Register Office in Bradford on Boxing Day of 1898 involved William of Rangers fame – the wedding certificate noted his age as 40, his profession was given as commission agent and his father’s name was listed as Peter MacBeth (deceased), whose occupation had been a ‘stuff merchant’. Intriguingly, however, William listed himself as a widower when there is no documented evidence to suggest that his first wife Jeannie had even died. In fact, it seems she continued to live until 1915, at which point she passed away in Bristol from ovarian cancer.

The evidence to suggest William’s second marriage was bigamous is persuasive, not least for the lack of any official confirmation of Jeannie’s passing in the first place. Indeed, in the 1901 census she appeared to have adopted the more anglicised Christian name of Jennie and was living in a boarding house in the town of Rochford in Essex. This Jennie MacBeth also listed a middle initial of ‘Y’ (as in Yeates or Yates, Jeannie’s unusual middle name). To add to the weight of evidence, her birthplace was confirmed as Glasgow, just like William’s first bride. She listed herself as a widow who was ‘living on her own means’ and this marital status is likely to have been a front to maintain respectability. It is no surprise she was not listed as living with any of her three children – William disappears completely from the records after 1890, while, in 1901, Agnes would have been 19 and was working as a nursery governess in Torquay. Norman, then aged 11, had been sent north to live with his grandmother, also Agnes, and aunts Jessie and Mary in their home at No. 26 Stanmore Road, Cathcart, further underlining the strife the marriage break up had caused to the family unit. (As an aside, it appears that Norman lived the majority of his life in Scotland until his death in 1973, aged 83. A customs official, he never married and died of prostate cancer at his home in the west end of Glasgow, a stone’s throw from the former Rangers ground at Burnbank).

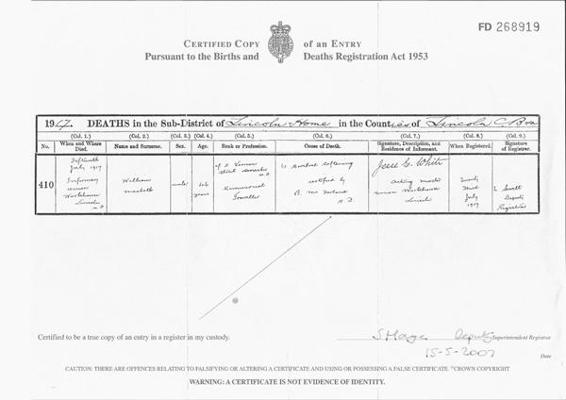

Following the trail of Jennie to her sad death in 1915 also adds strongly to the belief she was William’s estranged wife. Significantly, Jennie had returned to Bristol from Essex in the early years of the 20th century and died on 23 January 1915 at No. 18 Canton Street in the St Paul district of the city, only a few streets from the home at Albert Park where William and Jeannie had first moved in around 1880. The death certificate for Jennie MacBeth lists her age as 51 (again, like the 1901 census, seven years out) and her husband’s occupation was listed as commercial traveller, although his name was given as James, not William. The records for Scotland, England and Wales show that no such marriage between a James MacBeth and anyone named Jeannie or Jennie took place in the 40 years before 1915. On the basis of extensive research efforts, it is highly unlikely to have been anyone other than William’s first wife from their marriage in Glasgow in 1878.

If William was hoping for greater happiness from his second marriage, however questionable its legitimacy, he would not find it, as his life deteriorated towards a sad conclusion in 1917 when he died in the workhouse at Lincoln; penniless, forgotten and most likely the victim of dementia that led him to be officially cast as a ‘certified imbecile’. Soon after his second marriage to Sarah Ann in Bradford they moved to Lincoln, nearer his new wife’s birthplace of Welton-Le-Marsh, a few miles from Skegness. Born in 1859, she grew up in the Lincolnshire village with her five siblings and half siblings. Sarah Ann’s life, like her husband’s, was also fated to be spent in poverty, with several spells in and out of the workhouse at Bradford and Lincoln. On the surface, all appeared well in their lives and by the time of the 1901 census they appeared to be happily settled at No. 34 Vernon Street in Lincoln, a row of modest terraced houses which had been built in the late 19th century and that could nowadays double as the set for Coronation Street, even down to the pub on the corner. Incidentally, there is no disputing the identities of the couple at No. 34 Vernon Street. Sarah Ann’s birthplace is listed as Welton-Le-Marsh in the 1901 census, while her husband’s is given as Callander, Perthshire. The Lincoln Post Office Directory of the time, published every second year, listed William’s occupation as insurance agent and by 1903 the couple had moved along Vernon Street to No. 5, where they lived until at least 1907. By 1909 their address was published as No. 57 Cranwell Street, four streets parallel to Vernon Street and only a mile from Lincoln town centre. From 1907 William’s occupation was listed simply as ‘agent’, but after 1910 the name of MacBeth disappeared from the index of addresses for good.

Unfortunately, as he approached his 55th birthday, William was heading down to the lowest rung of society, where the only succour for the needy and infirm was provided by the workhouse. Lincoln had had a workhouse, also often referred to as a poorhouse, since around 1740, with accommodation for up to 350 people in an ‘H’ shaped building, made up of two dormitory wings and a central dining area in between. A resident could give three hours notice and leave at any time, but it was not a realistic option for all. A parliamentary report of 1861 found one in five residents had been in the workhouse for five years or more, mostly the elderly, chronically sick and mentally ill. Undoubtedly, William (and also Sarah Ann) fell into this category, because as economic conditions improved in the latter part of the 19th century fewer and fewer able-bodied people were entering workhouses. Indeed, by 1900 many were voluntarily entering the workhouse, particularly the elderly and physically and mentally infirm, because the standards of care and living were better than those on offer outside. Life in the workhouse may have been repetitive, but at least it was healthier than the poorest living quarters outside its walls and from 1870 onwards there was a relaxation of the rules that allowed books, newspapers and snuff for the elderly.

Cranwell Street, Lincoln: one of the last places William McBeath called home.

It was against this backdrop that William was admitted in January 1910 and it is not only his age, listed as approximately 15 years out at 39, that raises an eyebrow. The Creed Register for Lincoln Workhouse, held at the Lincoln Archives, notes the ‘name of informant’ on William’s entry records as simply ‘prison warder’. Unfortunately, very few records for Lincoln Prison, first opened in 1872, survive from the turn of the 20th century and those that do are still closed under the 100-year rule. Workhouse historian Peter Higginbotham2 called on his experience to back the suspicion that William may have spent a short spell in gaol at around this time, most probably for a petty offence. He was quite possibly referred on his release to the workhouse, which was situated only a couple of hundred yards from the Lincoln Assize Court.

The Creed Register discloses that William was discharged from Lincoln Workhouse on 3 June 1911, 18 months after he first entered, but he was back behind its gates within seven days. This time, on 10 June 1911, the records reveal he was ‘brought in by police’. It is difficult to escape the conclusion, particularly on the back of evidence from later workhouse records, that law officers were fulfilling a social work function by directing William to a more suitable environment. Frustratingly, although the Creed Register and board minutes of the Lincoln Workhouse are available, many of the more in-depth records, including medical reports, remain secured under the 100-year rule, so a clearer picture may not emerge for some years to come.

William’s personal decline appears marked and it is clear he could not look to his equally troubled second wife for support. She had admitted herself into Lincoln Workhouse on 6 December 1910 and was discharged six months later on 12 May 1911 (a month before William, which may have prompted her husband to return to the outside world). The relationship was clearly not loveless and at least once in August 1912 Sarah Ann made an attempt to secure her husband’s release. The Lincoln Workhouse minutes from 6 August noted: ‘Mrs MacBeth appeared before the board and asked for her husband, who is a certified imbecile, to be discharged from the workhouse into her care and the question was deferred for a report by Dr McFarland upon MacBeth’s state of mind.’ A fortnight later, on 20 August, the minutes noted a second request, adding: ‘Mrs MacBeth…asked for her husband to be discharged from the Imbecile Ward into her care and it was agreed to allow Mrs MacBeth to take her husband if the Medical Officer would certify him as fit to be discharged from the Imbecile Ward.’

The Mental Deficiency Act of 1913 officially defined four grades of mental defect, listing an imbecile as someone ‘incapable of managing themselves or their affairs.’ The 1913 Act specifically stated the condition had to exist ‘from birth or from an early age.’ Clearly, that did not apply to William, but there was no one in his life when he was first admitted to Lincoln Workhouse in 1910 to clarify a medical history from childhood that would enable doctors to make a rigorous medical assessment in terms that would dovetail with the official criteria three years later. In fact, the term ‘imbecile’ originally came from French via Latin, where it was defined similarly to the condition we now recognise as Alzheimer’s, a dementia in which sufferers mentally regress towards childhood. Certainly, the minutes of the Lincoln Workhouse indicate the inhabitants of the imbecile ward could not have been treated less like Oliver Twist. The notes of 15 May 1915 sympathetically recorded: ‘The clerk was directed to invite tenders for taking the imbeciles for drives during the summer months, as in previous years.’ Residents were occasionally taken on trips to Cleethorpes and there were also concerts held in the dining hall.

There is no doubt that the William in the Lincoln poorhouse was the same boy from Callander, despite the 15-year difference in the age recorded by the official workhouse documents. As we know, Sarah Ann MacBeth also spent six months in the same establishment in the first half of 1911, before pleading for his release the following year. Her appeals to have William given over to her care fell on deaf ears and it was clearly not just a result of authority’s concerns about his declining mental health. By 1911, the MacBeths had given up their home at No. 57 Cranwell Street and Sarah Ann gravitated back to Bradford soon after, confirmed by the Lincoln Workhouse minutes from 30 March 1915. They revealed: ‘A letter was read from the Bradford Union (workhouse) alleging the settlement of Sarah Ann MacBeth, aged 56, to be in this union. The clerk reported that her husband had been an inmate of this workhouse for several years and the settlement was accepted.’ In effect, Bradford turned Sarah Ann over to the workhouse where she had previously spent some time, claiming Lincoln was responsible for her care because her husband was a long-term resident there, which was acknowledged. Bradford Archives have confirmed the workhouse records of the town from the first decades of the 20th century. Sarah Ann admitted herself to Bradford Workhouse on 3 March 1915. Her address, before admission, was given as No. 149 Manningham Lane, Bradford. Her nearest relative lived at the same address and was named Adelaide Townsend – Sarah Ann’s half sister, four years her senior, confirmed by census records dating back to 1861 from their birthplace in Welton-Le-Marsh. Adelaide’s husband, Adolphe Townsend, also acted as a witness for the wedding of William and Sarah Ann in 1898.

Unfortunately, the creed register does not recall how long Sarah Ann spent under the same roof as her husband, but it would not have been much beyond two years, as William died in the infirmary at the Lincoln Workhouse on Sunday 15 July 1917. The official cause of death was ‘cerebral softening’, which indicates a stroke or brain haemorrhage, probably relating to his mental state. His death certificate recorded his age at 46 (it should have been 61), his previous address as No. 2 Vernon Street (he lived at Nos 5 and 34) and his occupation as commercial traveller. The informant of his death on the certificate was Jesse E. White, the acting master of the Union Workhouse, Lincoln. The fate of Sarah Ann is unknown.