The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 (18 page)

Read The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 Online

Authors: Gary Ralston

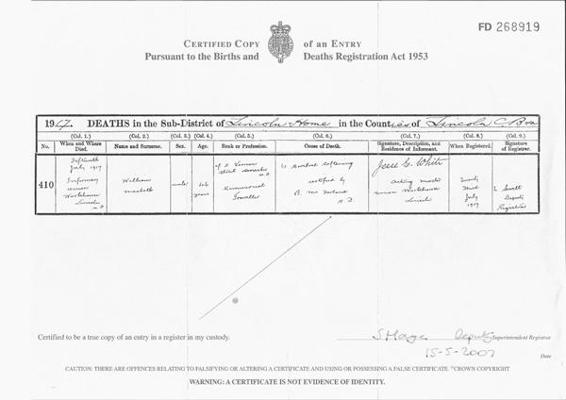

William McBeath’s death certificate: there are discrepancies in his age and address, not unusual at the time. Not surprisingly, his passing in 1917 went entirely unreported in the Scottish press.

The Lincoln Workhouse has long gone. The workhouse system was abolished in 1930 and although the Burton Road site was used as an old folks’ home for over three decades it was demolished in 1965. However, little has changed in the physical appearance of Vernon Street and Cranwell Street beyond the ubiquitous modern-day sight of cars parked bumper to bumper down the length of each road. Vernon Street sits around the corner from Frank’s Italian barber shop and across the road from Cartridge World and Blockbuster, with the Miller’s Arms, not the Rovers Return, sitting on the corner. Further down the street a converted mill development and gaily painted soffits and window frames suggest the street is winning its battle for 21st-century gentrification. However, further along, overgrown gardens and an exterior festive decoration of Santa Claus clambering for the chimney, even though it is the middle of May, suggest it might still have some way to go. Unfortunately, the net curtains drawn tightly across the bay windows at Nos 5 and 34 do not twitch with the ghosts of Christmas past. A two-minute walk allows the footsteps of William over a century earlier to be followed, although it is doubtful he made his way past three Indian restaurants, a Brazilian foodstore and the Mamma Mia pizzeria on his way to Cranwell Street in 1909. It is slightly more residential than Vernon Street and the red brick of its terraced homes would not look out of place in G51 itself.

Left: Canwick Road cemetery in Lincoln: the last resting place of William McBeath. Right: A sorry end: William McBeath lies under this holly bush, sharing a lair with a total stranger, in a pauper’s plot that was never marked.

Unsurprisingly, William was buried without ceremony on 19 July 1917, four days after his death. The rights to plot A2582 where he lies were never privately purchased, which means they were owned by the council and he was given a pauper’s burial. He rests on top of a total stranger, a Catherine Brumby, buried two decades before his death. The man who helped give birth to a club that spawned Meiklejohn, Morton and McPhail, Woodburn, Waddell and Young, Baxter, Greig and McCoist, lies in a pitiful, indistinct plot, under a holly bush in the forgotten fringes of the burial ground, unmarked and unrecognised behind a neatly tended resting place to a William Edward Kirkby, who died in September 1694, aged 26. The skilled assistance of cemetery staff and their dog-eared burial chart over a century old are required to even find the site where William is buried – and it is no treasure hunt. Picking the way back on the path, fine views are afforded up to Lincoln Cathedral, which dominates the horizon for miles around in this flat corner of England. Here is hoping God is looking over William better in death than he ever did in life.

The FA Cup – From First to Last

THE FA Cup has attracted many sponsors in recent years, but the commercial worth of the tournament remained unexploited throughout the latter half of the 19th century. If English football bosses sought financial inspiration from the raucous exploits of the Rangers squad in the only season in which they participated, back in 1886–87, they could surely have attracted a bidding war for competition rights between Alka Seltzer and Andrew’s Liver Salts. These were more innocent times (thankfully for Rangers, that also included the media) as they kicked off their campaign at Everton amid accusations of over-drinking and ended it at the semi-final stages against Aston Villa at Crewe surrounded by allegations of over-eating.

The Football Association Challenge Cup has enjoyed a long and distinguished history from its first season in 1871–72, when 15 clubs set out to win a competition that quickly developed into the most democratic in world football, where village green teams can still kick-start a campaign in August and dream of playing at Wembley against Manchester United the following May. Queen’s Park were among the first competitors, alongside others whose names reflected the public school roots of the tournament, not to mention its southern bias – the Spiders and Donington Grammar School were the only sides who came from north of Hertfordshire that first season. The first FA Cup trophy cost £20 and Queen’s Park contributed a guinea to its purchase, a staggering sum for a club whose annual turnover at the time was no more than £6.

Wanderers Football Club, based near Epping Forest, won the first tournament against the Royal Engineers 1–0 at The Oval, but only after Queen’s Park scratched their semi-final replay. In a portent for the zeal with which football would soon be greeted in Glasgow, the inhabitants of the city raised a public subscription to cover the cost of sending the Spiders to London to face the Wanderers, but they could not afford to stay in the capital for a second match and returned home unbowed and unbeaten. In addition to their failure to see through to the end their first FA Cup campaign, there would be other losers as a result of their participation in the competition – keen students of association football in the Borders. Queen’s Park were forced to abandon a week-long tour of the Tweed, where they had promised to undertake their fine missionary work in the towns and villages, in order to play in the Cup competition. They never did make their visit and association football lost out to the oval ball game in the affections of a public in an area where the culture of rugby remains strongest to this day.

In the beginning of the game, all British clubs were eligible for membership of the Football Association, their calling card for the FA Cup, so it was no surprise to see sides such as Queen’s Park from Scotland and the Druids and Chirk from Wales lining up against sides from the counties and shires of England. However, for the most part Scottish club sides resisted the temptation to turn out in the first decade or so of the competition, particularly as cost was such a significant factor. Indeed, throughout the 1870s Queen’s Park regularly received byes to the latter stages of the competition in a bid to keep their expenses low, but either scratched or withdrew as the financial realities restricted their ability to travel. The FA, responding to the increased popularity of the tournament, particularly in the north of England, began to organise ties on a geographical basis as the 1870s gave way to the 1880s and suddenly Queen’s Park returned to the fore to an English audience. In 1884 and 1885 they reached the Final, only to lose narrowly on each occasion to Blackburn Rovers. Until that point, Queen’s Park were the only Scottish team to have made significant strides in the FA Cup but, perhaps buoyed by the success of the Spiders, by the third round of the 1886–87 competition there were four Scottish teams who had won through from an original entry of 126 clubs – Partick Thistle, Renton, Cowlairs and Rangers.

In actual fact, the Rangers name had been represented in the FA Cup as early as 1880, when they advanced to the third round before being humbled 6–0 at The Oval by the 1875 tournament winners, the Royal Engineers, but the information is misleading. The Rangers team who competed in 1880 and 1881 were an English outfit who included in their ranks an F.J. Wall, who would later become secretary of the Football Association. He seemed none too disheartened to be on the end of such a heavy defeat, particularly against such illustrious opponents as the Royal Engineers, and later admitted fortifying himself for the game ‘with a splendid rump steak for lunch.’1

It was not – at that stage anyway – the state of the pre-match meal that concerned the Rangers as they prepared for their first game in the competition against Everton on Saturday 30 October 1886, but the demon drink. Excitement must have been high among Rangers’ players during the 1886–87 season at the prospect of playing in the FA Cup as they boarded the train at Glasgow, bound for a game in a competition in which they had only once before come close to competing. Rangers had decided to take up membership of the Football Association at a committee meeting in June 1885 and Walter Crichton, who would soon be named honorary secretary of the club, was listed as its delegate to the FA. Subsequently, Rangers were drawn to face Rawtenstall in the first round of the Cup, but Rangers refused the match on the basis that the Lancashire club had paid professionals among their ranks of registered players. Professionalism had finally been legalised within the English game at a meeting of clubs in July 1885, but with strict conditions for participation in the FA Cup, including birth and residence criteria, with all players also subject to annual registration demands. Of course, at this stage the payment of players was still a strict taboo – publicly at least – in Scotland and the SFA frowned upon games played against English teams who knowingly employed professionals. The FA fined Rangers 10 shillings ‘for infringement of rules’, although stopped short of telling the Kinning Park committee which rule had been broken. Rawtenstall were subsequently banned from the competition after playing out a 3–3 draw against near neighbours Bolton in the next round, apparently for breaches of the strict FA conditions in their Cup competition relating to the employment of professionals.

Tensions had eased slightly 12 months later as Rangers arrived in Liverpool in high spirits for a game against the underdogs of Everton. The previous campaign had been a miserable one for the Kinning Park regulars, with an early exit from the Scottish Cup at the hands of Clyde following a 1–0 defeat and an indifferent series of results against often mediocre opposition. Tom Vallance, who had just been returned for his third year as president, had promised three trophies at the start of the season – the Scottish Cup, the FA Cup and the Charity Cup. However, the club’s hopes of winning silverware proved as elusive as their bid to turn a profit – Rangers lost £90 that season, mostly as a result of their early Scottish Cup exit, although the Kinning Park bank book still held funds of almost £130. Still, the Scottish Athletic Journal could not contain its glee as it threatened to present Vallance with three teacups to parade to members at the club’s next annual general meeting.

West Scotland Street, Kinning Park, c.1905. The Kinning Park ground was at the very bottom of the street, behind the tenement to the left of the lamp post. Residents feared the site was haunted in the lead-up to the 1877 Scottish Cup Final. In fact, the howls and yells came from the Rangers ‘moonlighters’, practising all hours in preparation for the challenge of Vale of Leven. The baths were pulled down in the 1970s to make way for the M8 motorway.

The start of season 1886–87 promised better to come, despite the spectre of relocation from Kinning Park hanging over the club as its lease on its third ground neared its end, but the squad would not be fortified with the Assam blends so familiar to Vallance following his time in India. There was certainly mischief in mind when Rangers travelled to Liverpool the evening before the game against Everton, who had been knocked out of the FA Cup the previous season 3–0 by Partick Thistle. The Kinning Park squad arrived in Liverpool the worse for wear for a game in which they were overwhelming favourites. These days, the former Compton Hotel in the city’s Church Street houses a branch of Marks and Spencer, but it was bed and not bargains on the mind of the bedraggled Rangers squad as they trooped in there on the morning of the game after being thrown out of their original digs. The columnist ‘Lancashire Chat’ noted matter-of-factly in the Scottish Umpire of 2 November 1886: ‘The Rangers arrived (in Liverpool) soon after midnight and roused the ire of the hotel proprietor in their night revels. In fact, the Rangers squad were bundled out bag and baggage without breakfast and took up their quarters at the Compton Hotel…They dressed at the hotel and the game was started pretty punctually.’2 In the 21st century the media would enjoy a field day with the story, but in those more innocent times observers of the fledgling football scene were less inclined to saddle up on moral high horses at a lack of professionalism among players who were entirely amateur, or purported to be so.

Historically, the Victorian era has been regarded as one of austerity and respect for place and position, but in truth, anti-social behaviour was never far from the fore in the Scottish game, which is hardly surprising when by 1890 it was estimated that one third of the total national revenue in Britain came from alcohol.3 In 1872, the year of Rangers’ formation, 54,446 people in Glasgow were apprehended by police for being drunk, incapable and disorderly.4 Social commentator Sir John Hammerton painted a vivid and horrifying picture of a drink-soaked society which, sadly, does not appear to have improved much in the century since his publication of Books and Myself. He wrote: ‘In 1889 Glasgow was probably the most drink-sodden city in Great Britain. The Trongate and Argyle Street, and worst of all the High Street, were scenes of disgusting debauchery, almost incredible today. Many of the younger generation thought it manly to get “paralytic” and “dead to the world”; at least on Saturday there was lots of tipsy rowdyism in the genteel promenade in Sauchiehall Street, but nothing to compare to the degrading spectacle of the other thoroughfares, where there were drunken brawls at every corner and a high proportion of the passers-by were reeling drunk; at the corners of the darker side streets the reek of vomit befouled the evening air, never very salubrious. Jollity was everywhere absent: sheer loathsome, swinish inebriation prevailed.’5

Football then, as now, mirrored society and Rangers players occasionally let themselves down. In March 1883, a columnist in the Scottish Athletic Journal commented: ‘High jinks in hotels by football teams are becoming such a nuisance that something must be done to put an end to the gross misconduct which goes on. I was witness to a ruffianly trick in the Athole Arms on Saturday night. A fellow – I will call him nothing less – as a waiter passed with a tray full of valuable crystal deliberately kicked the bottom of the tray and broke a dozen of the wine glasses to atoms. In the crowd he escaped notice, but the Rangers will, of course, have to pay for the damage. I cannot see any fun in a low act of this kind.’6

Of course, Rangers were not alone in drawing criticism for their alcohol-related antics on and off the field. Dumbarton won the Scottish Cup after a replay in 1883, for instance, but only after it had been hinted by football columnist ‘Rover’ in the Lennox Herald that one or two of their players had partaken of whisky before the first match, which finished 2–2. After the second game, a 2–1 win over arch rivals Vale of Leven, a group of Dumbarton players headed for a few days’ celebration at Loch Lomond with assorted wives, partners and pals. Returning home on two wagonettes on the Monday and ‘boldened by excessive refreshments’ they took no time to remind locals of the weekend scoreline as they lurched through Vale of Leven. Predictably, a rammy ensued, during which two buckets of slaughterhouse blood were thrown over the Dumbarton group.

Public houses were regularly used as changing rooms for teams, particularly in Ayrshire, and while the Highlands are synonymous with hospitality, it was another matter in Angus as Forfar treated their players to a half bottle of whisky and a bottle of port after every game, while visitors were restricted to a pie and a pint in 1890. One club, the Pilgrims, vowed never to visit Dundee again after the Strathmore club tried to entertain them after a game on the derisory sum of only five shillings and sixpence. Reporting on the Pilgrims’ point of view, the Scottish Athletic Journal lamented: ‘Can one blame them?’7 Not even Queen’s Park, the grand standard-bearers of the time, could escape the negative influence of alcohol when two players were fined 20 shillings each by Nottingham magistrates for being drunk and disorderly after a match in the town in January 1878.

For the non-professional Scots, trips to England generally took place at holiday times, with New Year and Easter particular favourites. Football often came a poor second to the festivities and the attitude of the press was as schizophrenic as the nation’s relationship with alcohol itself. Therefore, the Scottish Athletic Journal reasoned early in 1885 that ‘a New Year holiday trip does not come every day and youthful blood must have its fling…the honour and glory of Scottish football is cast to the winds and the present is only remembered.’8 This was a complete reversal from its stern editorial two years previously when it noted: ‘Generally, when any of our association teams go to England they run riot with everything and everybody they come across. They stick at nothing, not even dressing themselves in policeman’s clothes and running pantomime-like through the streets with roasts of beef not of their own. This was what the frolics of one of our leading teams consisted of when in Manchester last Christmas.’9 By sheer coincidence, Rangers were in Lancashire at that time for a game against local club Darwen.

In these days of Premiership millions it is perhaps surprising to learn that Rangers were strong favourites in the first round against Everton, even though the home side had recently won the Liverpool Cup and had been undefeated all season. In a burst of patriotism, the Scottish Umpire declared in its preview to the game: ‘Dobson, Farmer and Gibson are not eligible [for Everton]. And without them they have not much chance of winning…without the three named, Everton cannot possibly defeat a decent team of the Rangers.’10 The match was played at Anfield and the Scottish Umpire remarked that the ground was not a very good one, particularly as it was situated a couple of miles from the nearest railway station. However, football in Liverpool at that stage was, according to the newspaper, ‘leaping and bounding’.

Rangers were handed the tie before kick-off – unsurprisingly, delayed 15 minutes to give the players time to arrive at the ground after shaking off their excesses – when Everton ‘scratched’ the tie to give their three ineligible players the chance to play and make the encounter more competitive. The game almost did not start as a result of a morning deluge that had turned the playing surface into a mudbath, but the skies cleared to blue by lunchtime and soon the crowds were rolling up in their thousands. The match report from the Liverpool Courier gives an idea of how established Rangers had become in the 14 years since the club’s pioneers had first taken to the game at Flesher’s Haugh. The Courier reported: ‘The visit of the Glasgow team to the popular Anfield enclosure on Saturday excited such a large amount of interest that there could not have been less than 6,000 persons present to witness the play. Not only were the capacious stands well filled but every available point of vantage was early taken possession of, so long before the game commenced the enclosure presented an animated scene. The game was undoubtedly one of the best that has been witnessed on the Anfield ground during the present season. It was fully a quarter of an hour after the advertised time before the teams put in an appearance. When they did so the Rangers, by their fine physique, gained many friends, but this could not diminish confidence in the ability of the Evertonians to uphold the credit of the district.’11

Rangers won the game courtesy of a one-yard tap-in from striker Charlie Heggie after 20 minutes. Everton fought valiantly to get back into the game, but Rangers held out and even had a second goal disallowed late on. ‘Lancashire Chat’ later recalled in the Scottish Umpire: ‘Tuck McIntyre was in a happy mood and seemed to enjoy himself, whether knocking an opponent over or kicking the ball. [Afterwards] the Rangers drove off to the Compton and [then] returned to the Everton headquarters, where a pleasant evening was spent. The Glasgow men were accompanied by about half a dozen of their supporters and Hugh McIntyre came down to see his old comrades perform. Tom Vallance made a pretty speech, the remarks of the handsome international being received with great cheering. The smoking concerts have evidently improved the vocal attainments of the team and [John] Muir made a very successful debut at Everton. The Liverpool club’s vice-president turned out in full force to welcome the Rangers, who left well pleased with their outing.’12

The club’s subsequent early round Cup ties, all played at Kinning Park, were to prove less eventful than the trip to Liverpool. Three weeks after the defeat of Everton another English outfit, Church, were put to the sword in a 2–1 victory, with two goals from Matt Lawrie, a dribbling winger who had been signed from Cessnockbank in the summer of 1884. Lawrie found the net again on 4 December when Springburn side Cowlairs were knocked out 3–2 at Kinning Park, with Bob Fraser and Matt Peacock also scoring for the Light Blues. Rangers were guaranteed to be playing FA Cup football into 1887 when they received a bye in the fourth round and were drawn, again at home, to Lincoln on 29 January.

On the face of it, the 3–0 victory over the English side that set the Light Blues up for a quarter-final crack at Old Westminsters seemed academic. A swirling wind made playing conditions difficult at Kinning Park, but Rangers scored twice in the first half courtesy of strikes from Fraser and new boy Joe Lindsay, a Scotland forward who had previously played at Dumbarton but who had been tempted to Kinning Park during the festive period of 1886 as it was closer to his workplace in Govan. The third goal from Peacock sealed a comfortable win and Donald Gow so impressed Lincoln with his performance in defence that he was immediately offered a weekly wage of £2 10 shillings, a king’s ransom at the time, to move south.

Gow refused the offer, but the English press were far from happy at the presence of Lindsay in the side and chided the amateur Rangers for alleged professionalism, which was still a strict no-no in the Scottish game under the terms of the SFA, even in the FA Cup. The Midland Athlete newspaper bemoaned the fact that Lincoln City had to meet ‘a team called Glasgow Rangers, but an eleven that would never be allowed to compete for the Scottish Cup under that name…the Rangers have called in extraneous aid for their national Cup ties.’13 An editorial in the Scottish Umpire hit back in a fit of nationalist pique: ‘The Light Blues played on the occasion referred to a team that could, if strong enough, have done duty in the Scottish ties without let or hindrance. Be sure of your fact, friend Athlete, before you launch out. It is awkward to be caught on the hop.’14

Nevertheless, the Midland Athlete had shone the spotlight on an issue that was becoming an increasing concern in the Scottish game, which would not embrace professionalism until the AGM of the SFA in 1893, eight years after England. Of course, payment of players had been around even before then, with Glasgow shipyard worker James Lang acknowledged as the first professional player in the history of the game when he left Clydesdale and accepted a financial offer to turn out for Sheffield Wednesday in 1876. Lang literally had one eye on a money-making opportunity – he lost the other in a shipyard accident but somehow managed to keep his handicap hidden from his new employers. In his latter years, Lang was a regular in the main stand at Ibrox and delighted matchday regulars with details of his ground-breaking claim to fame. The bountiful orchards of Scotland yielded a harvest of impressive players ripe for export over the border and, although many were from the industrial heartlands of the central belt and hungry to advance up the economic ladder, there were still those who were attracted to the game as a leisure pursuit and could afford to adopt a more laid-back attitude to otherwise tempting inducements. Pollokshields Athletic forward Frank Shaw, for example, delayed replying to an offer in 1884 of a handsome salary of £120 a year from English club Accrington after he had come to their attention at an earlier game. He wrote in reply that he could not give the matter his full attention until ‘my return from a fortnight’s cruise among the Western Isles, on my yacht.’15

English clubs quickly began to burst at the seams with the ‘Scots professors’, skilled players from north of the border who played and educated their new paymasters with all the zeal of tartan missionaries. The last time England had seen such an invasion of Scots was in the previous century when the Jacobite forces of Charles Edward Stuart marched as far south as Derby. This time, however, the Scots did not turn back, but stayed on and conquered, spreading their influence further across the country. The Liverpool team established by former Everton landlord Houlding, for example, kicked-off its first League campaign in 1893 with 10 Scots in its line up. The first goal scored in English League football was by a Scot, Jack Gordon, who would never have felt homesick at Preston North End. The greatest-ever Preston team, known as the Invincibles, won the first English League title (the brainchild of Perthshire draper William McGregor, the grand patriarch of Aston Villa) in 1888–89 without losing a match, retained the Championship the following season and also won the FA Cup in 1889 without conceding a goal. The spine of their great team was Scottish, including brothers Nick and Jimmy Ross and internationals David Russell, John Gordon and George Drummond, while former Ranger Sam Thomson also played for the club. Scots also dominated in Sunderland’s ‘Team of all Talents’, who won the English title in 1892, 1893 and 1895 and were even founded by a Scot, teacher James Allan, in 1880.